In her 1988 essay “The Fisherman’s Daughter,” Ursula K. Le Guin reflects on how women writers have long supported one another: “there is a heroic aspect to the practice of art; it is lonely, risky, merciless work, and every artist needs some kind of moral support or sense of solidarity and validation.”1 In content and form—a loosely assembled collage in which the author is placed in a position of kinship with her readers and those writers who came before—the essay shares much with “Crone Music,” an exhibition by Beatrice Gibson of two new films which are complemented by a program of screenings, rehearsals, readings, and performances by many writers, artists, and musicians who Gibson collaborated with for her films.

While Gibson’s work has long been made in relation to the work of others, these have usually been major male figures—William Gaddis, for example, or Cornelius Cardew—in these new films, the references are to more marginalized figures, notably women, queer communities, and poets. The exhibition’s title is borrowed from the 1990 album by Pauline Oliveros. Deux Soeurs Qui Ne Sont Pas Soeurs [Two Sisters Who Are Not Sisters] (2019) takes its title from a film script written in 1929 by Gertrude Stein, and although the film is not a straightforward adaptation, it does share a certain obliqueness with Stein’s text, which ends “et n’y comprennent rien” (“and they understand nothing”). Folded between the original story of the laundress, the two women with a sports car, and another woman who “looks as if she’s just won a prize at a beauty contest”—here compellingly played by the extraordinary Adam Christensen—Gibson has placed new elements that refer to the film’s making, most especially the fact that two of her performers became pregnant during it. (Stein’s scenario was also a partial response to a recent addition to her family, a white poodle called Basket.) The performers were asked to write letters to their unborn children and read them to camera. Alice Notley, a poet noted for her use of details of her own pregnancies, reads from her feminist epic Songs and Stories of the Ghouls (2011).

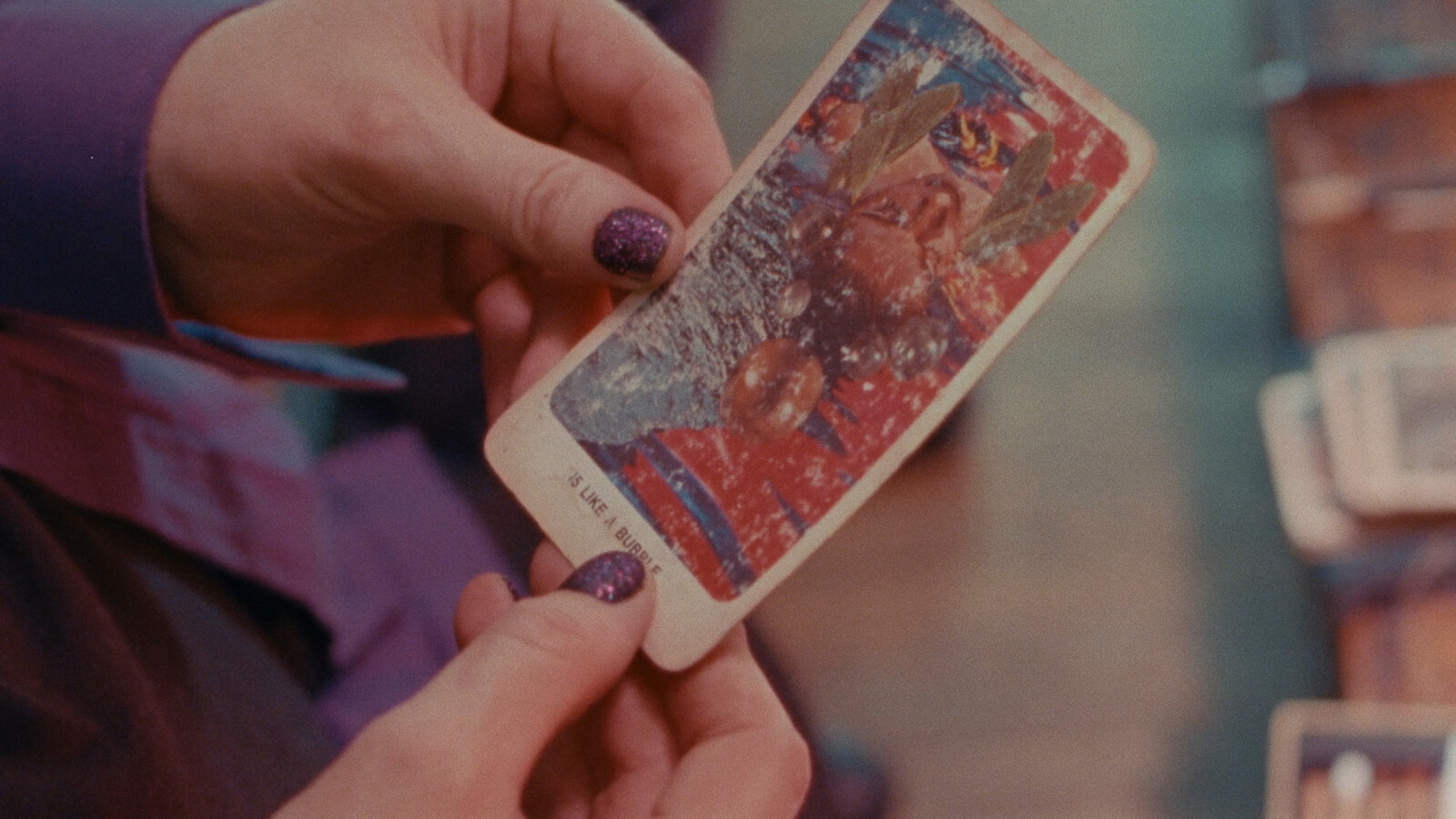

Gibson’s other film, I Hope I’m Loud When I’m Dead (2018), bears a strong resemblance to Deux Soeurs, sharing a set and even some shots. However, freed from an existing scenario, a more affecting film emerges. It opens with a feeling of panic on the London Underground, and then everything else seems about to expire: nature, society, others. We then find ourselves in a New York apartment with poets Eileen Myles and CAConrad, listening to the inauguration of Trump and turning tarot cards, as if it isn’t already clear what the future holds. Conrad reads from the poem which lends the film its title, Myles from her 2012 poem “My Box,” and, even if things can be put away, they can be shared, too. There are also extracts of poems by Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, and Notley once more, and with them a sense of Sara Ahmed’s idea of citation as a form of reproductive technology, one that not only replicates and puts into circulation the ideas of others, but also enlarges the possibilities of oneself. (One might ask who benefits most from such acts, however, and who benefits most here.) Gibson appears with her children and male partner on a beach; they share a bath. If her earlier sense of losing the boundary of her body felt like a violent imposition, here it becomes a tender connection, the becoming-other that is love. If, at the beginning of the film, Gibson feels anxious and lost, at its end she loses herself far more joyously, dancing ecstatically with her young son to Corona’s “The Rhythm of the Night,” just as Denis Lavant’s character Galoup does at the end of Claire Denis’s Beau Travail (1999).

In these films, and in the events programed around them, Gibson emphasizes the importance of community as a social formation, the means of creating artistic forms, and the means by which one can create a sense of oneself. Such acts are always marked by privilege, and fraught with difficulties—who can form such groups, and who can enter them, and with what ease. If the power relationships that exist here are muted, that is not to say that they can be effaced fully; in placing herself within the work, Gibson implicates herself, too. What is hoped for, despite this, is the solidarity about which Le Guin wrote: the support that would enable us better to live together. Just before Galoup’s dance, we see upon his chest a faded tattoo which reads “Serve the good cause and die.” That may well be our fate. But in these films we sense the possibility of—if not its opposite exactly—its complement: “Serve the good cause and live.”

Ursula K. Le Guin, Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places (New York: Grove Press, 1997), 212.