With every email I receive about new digital programs from museums, galleries, and other art institutions around the world, I feel more conflicted. My sympathy for these institutions, which had little warning before they had to shutter their doors and are now trying to recreate their program online, often for the first time, is coupled with frustration that giving a title to a group of JPEGs does not an exhibition make. Yet this is a moment to explore what exhibitions are, how they serve a general public, and whether there are models for their translation from physical to digital spaces.

The Biennale of Sydney, which opened on March 14, closed ten days later. Its organizers are currently working with Google to create a digital version of the exhibition that will include live content, virtual walkthroughs, podcasts, interactive Q&As, curated tours, and artist takeovers.1 Google Arts & Culture already offers virtual tours of museums and exhibitions around the world using Street View’s tools. On the company’s website is a list highlighting “6 Now-Closed Exhibitions That You Can Still Explore In Street View.”2 These include the 2015 Venice Biennale, Kara Walker’s massive sugar sculpture A Subtlety, presented by Creative Time at the empty Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn in 2014, a street art exhibition in a Parisian tower block that has since been razed, and a walk along Christo and Jean-Claude’s Floating Piers (on Lake Iseo in Italy, 2014).

Of course, Google documented those exhibitions under different circumstances. Viewers will approach a digital artifact differently when it replaces, rather than enhances, a cultural experience. When a fire spread in the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro in October 2018, 90 percent of the museum’s collection was lost in the blaze. The collection was never systematically digitized, but a Google Arts & Culture tour of the museum already existed. Now, it is presented as an online exhibition that invites users to “take a guided tour of the Museu Nacional before 2018’s fire.”3 The clumsy interface, with arrows digitally leading users down a street on Google Maps, is translated indoors as not-so-smooth jumps from one room to another, which sometimes push a user past the object they are trying to approach. The clunkiness becomes a reminder not just of the platform’s limitations, but also of the loss itself: it’s one thing to appreciate an aimless drift through the Louvre while you’re in quarantine thousands of miles away, it’s another when that’s all you’ve got, and will ever have.

With an eye to social distancing, emails from galleries, museums, and fairs prompt recipients to stay safe and state things like “We look forward to staying connected while we’re all apart” (Hauser & Wirth, announcing “Dispatches,” a program of events, performances, screenings, and online exhibitions, which began with a performance by Martin Creed aired live on Instagram). Few of these online programs attempt to really challenge the way we look at art online, and too often simply recreate offline structures. Art Basel presented Online Viewing Rooms, an online fair featuring the galleries that were scheduled to show in the canceled Hong Kong edition, running during the original fair’s opening dates. Four galleries that were meant to participate in the now-postponed Onesen Confidential—a collaborative group exhibition in which Tokyo galleries host international galleries—have decided to show video works in a two-week screening program on Vimeo, called Online Confidential (including MUJIN-TO, Tokyo, Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich, Union Pacific, London, and Jan Kaps, Cologne). In a gesture perhaps inspired by these collaborative exhibitions, which are becoming increasingly popular since the first iteration of Condo in London in 2016, David Zwirner is hosting 12 New York galleries in its online viewing rooms for the month of April. This initiative, called Platform, will subsequently continue with London and international galleries.

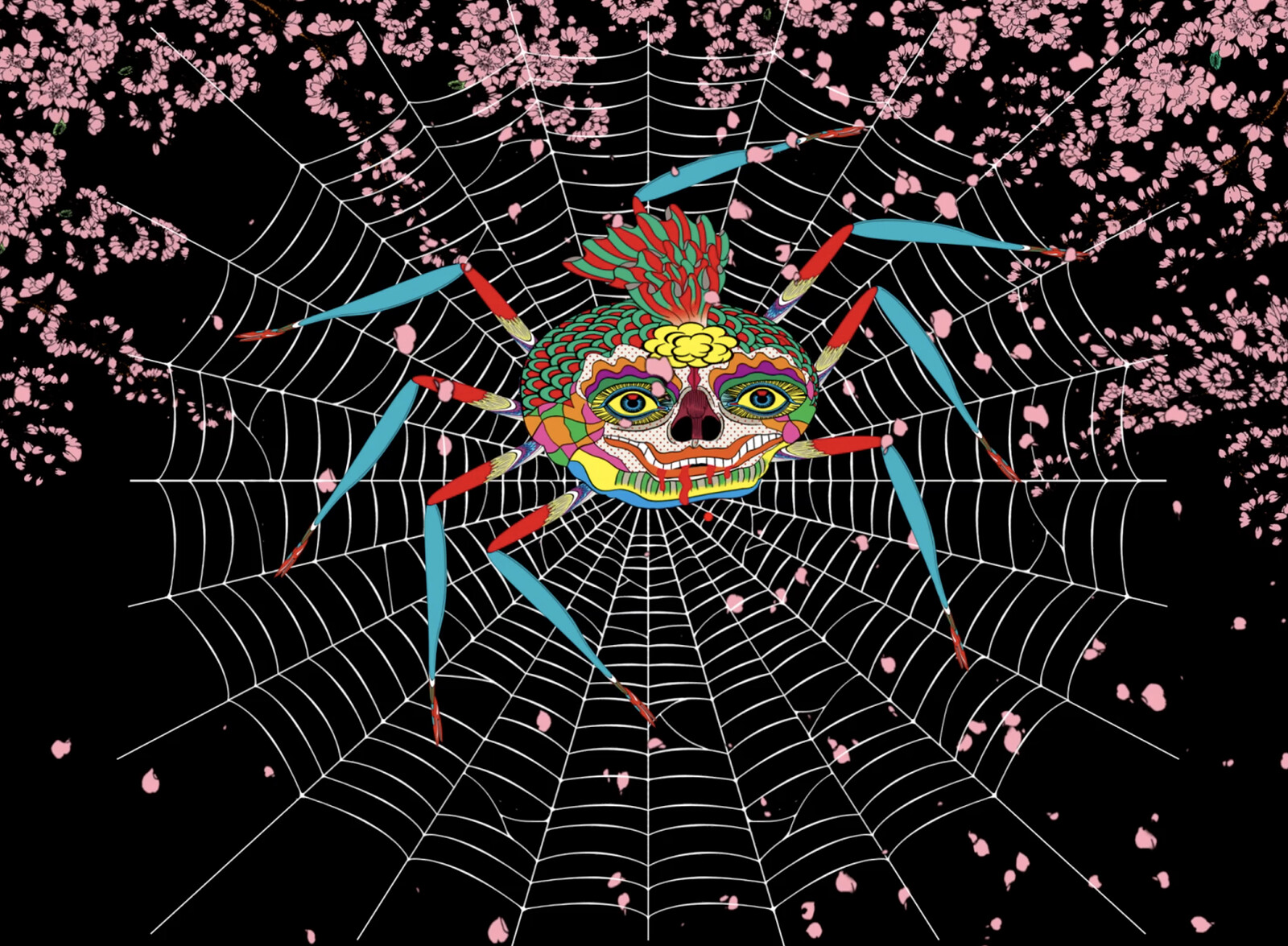

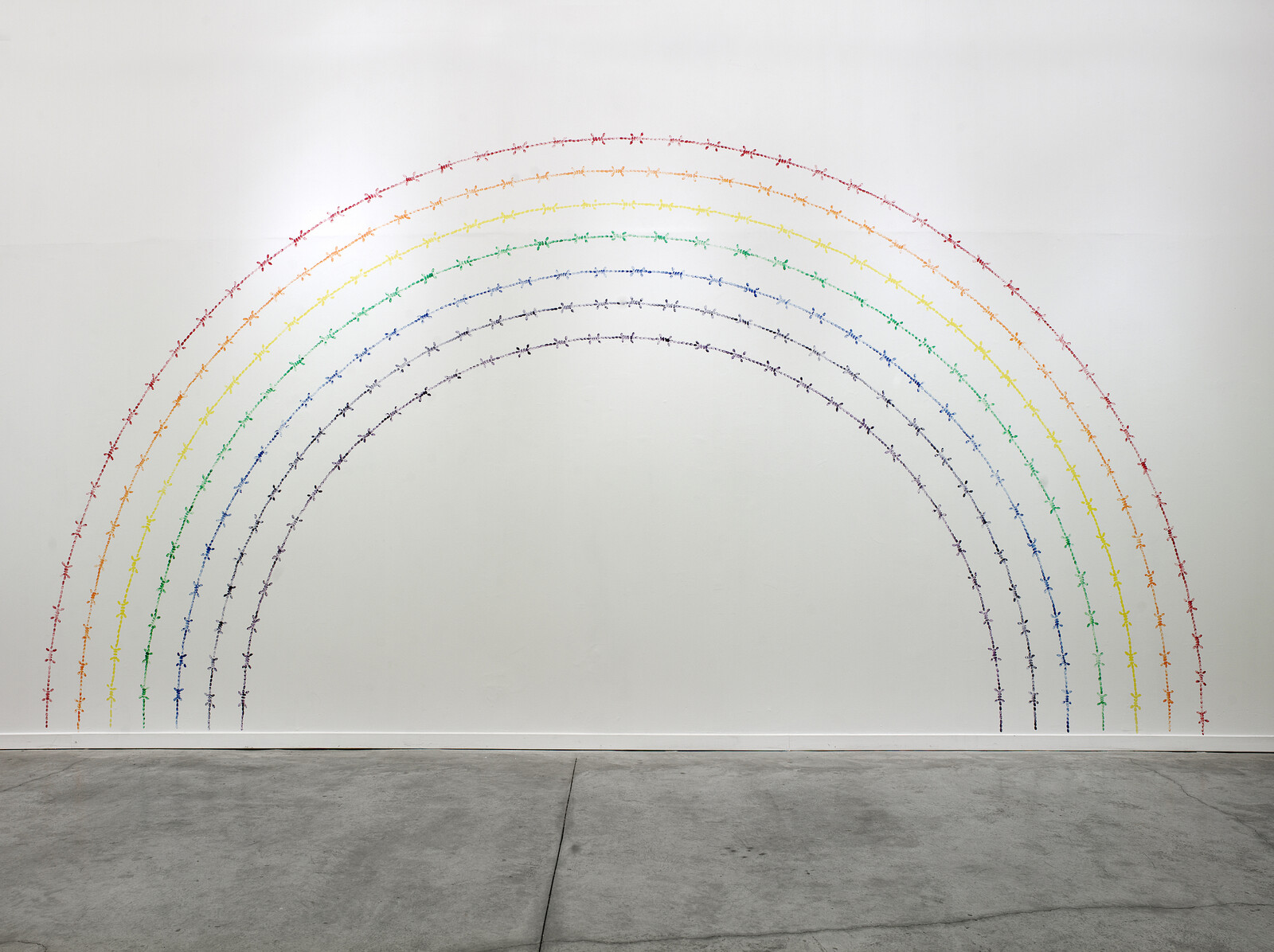

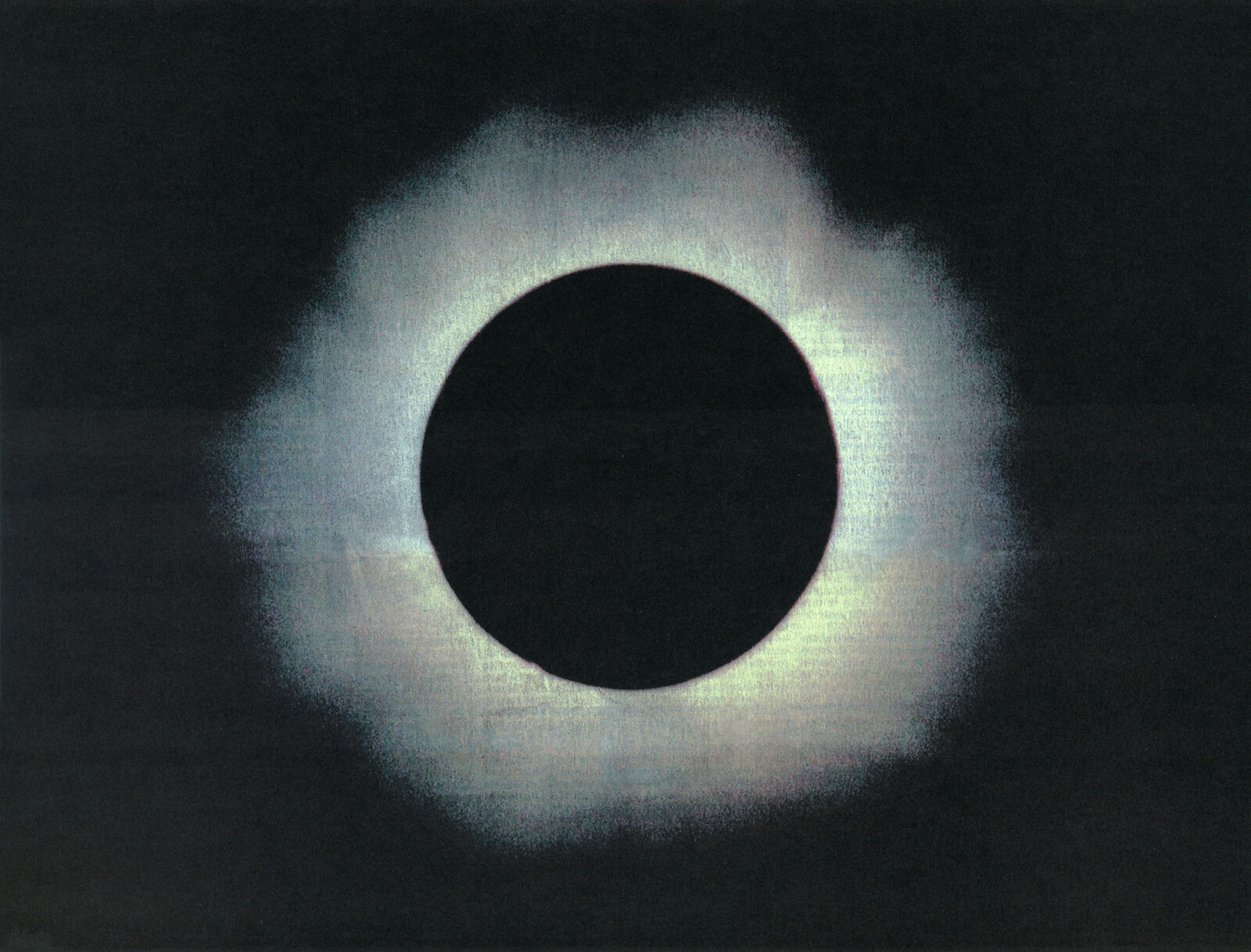

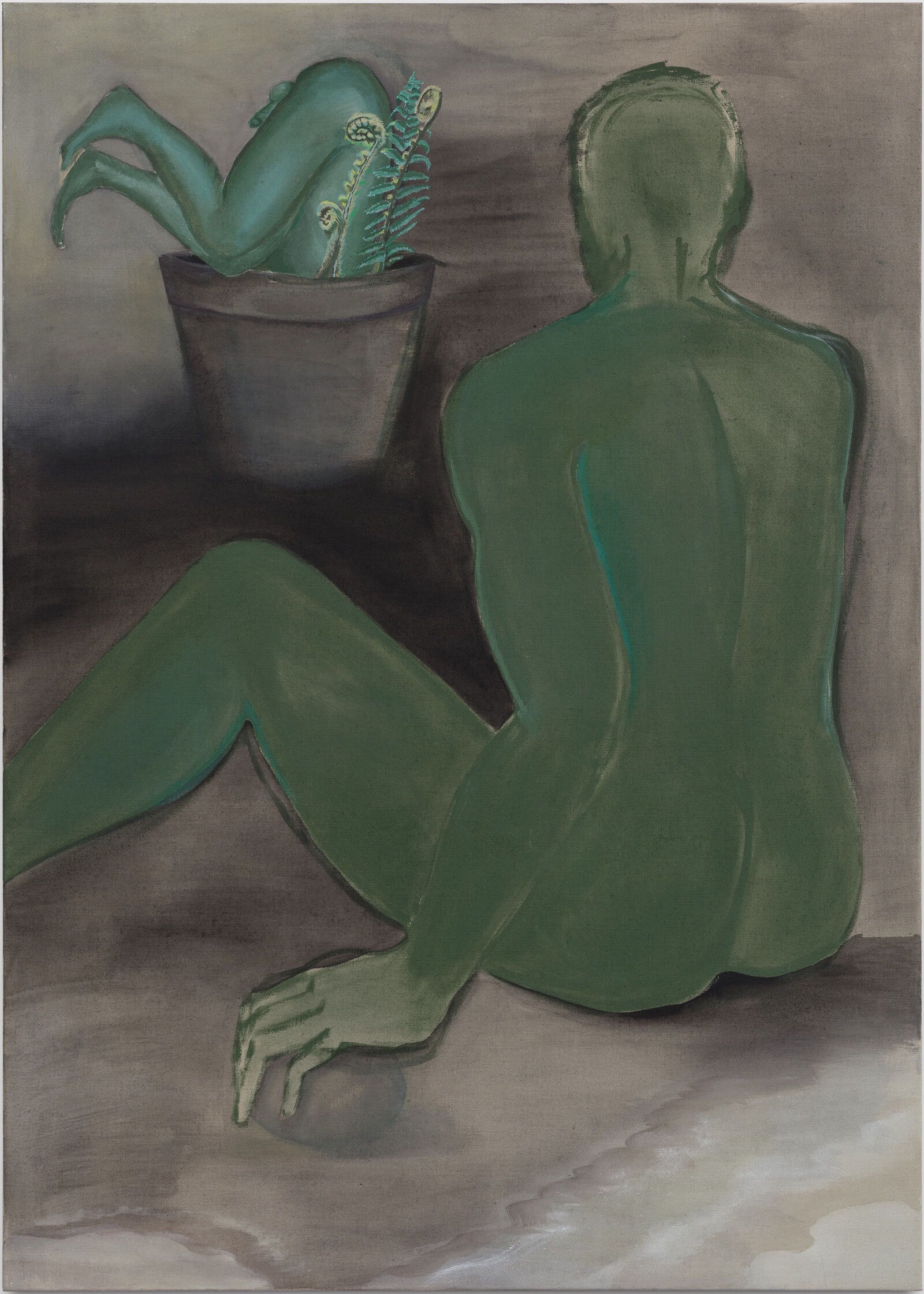

The M Woods Museum in Beijing was one of the first art institutions to move to an online-only presentation. Since February 13, the exhibition “Art Is Still Here: A Hypothetical Show for a Closed Museum,” curated by Victor Wang, has been expanded on a weekly basis with new artworks, thinking about online programing as a growing continuum rather than a series of often very short exhibitions. It’s an example of how an online program can operate differently from a physical exhibition, rather than simply mirroring recognizable formats. Other exhibitions succeed because they use the multimedia environment the internet allows, even in small ways. Tel Aviv and Brussels gallery Dvir curated a show titled “Corona”—not the virus, the Paul Celan poem from 1948 about the struggle to love after World War II (“we exchange dark words / we love each other like poppy and recollection”). A recording of the poet reading the poem in German forms a haunting soundtrack to Mircea Cantor’s colorful barb-wire rainbow mural (Rainbow, 2010), or Douglas Gordon’s series of lithographs taken from newspaper front-page photographs of the solar eclipse in August 1999. And the Biennale of Sydney’s attempt at creating a rich-media documentation of the show reflects the work of the artists included in it: several augmented-reality projects and a podcast series by Papua New Guinea-based artist and radio broadcaster Namila Benson will translate to a digital sphere in new, interesting ways.

Looking at these projects sparks new ideas about what a medium is. In the early 2010s, at the height of the discussion around how art is seen online, countless articles, conferences, and other projects examined how viewers interact with art on the internet and how galleries could sell there. This discourse, and the introduction of numerous new platforms to showcase, sell, or make art online, have flattened out in recent years: the history of online engagement with art is one of excitement quickly followed by surrender to the status quo. And then everything changed. What was once measurable, monetizable, desired, is now overabundant: attention. The question to follow is not whether art matters—now more than ever, etc.—but whether people can and will congregate around art, digitally, because that’s all there is now. We need to look at online programs not as a space to memorialize the exhibitions that were, or the exhibitions that could have been, but as its own medium. The status quo—some installation shots, a few JPEGs collected together, a Google Street View tour—just isn’t enough.

The internet is already a space of overproduction. A successful space for people to come together right now should begin with what art institutions are already doing—online or offline—and making a space where these meet: not just pointing to preexisting video documentation of a talk, or a podcast recorded months ago, but reflecting on how these can be revisited. And it doesn’t have to be temporary. It could mean a way of rethinking accessibility, archiving, and documentation. With this in mind, while we critique and think through these online exhibitions, we must not forget the tech criticism that has gained prominence in the last decade: it’s essential to remember that the internet is a system for surveillance, an ecological resource drain, a material concern even if it does keep us entertained and in touch.

This is already a visual time. We see numerous photographs of empty train stations, graphs of infection rates, the endlessly repeated yellow-and-red stock image of what a coronavirus looks like. We are homebound, in front of screens, which seems like a perfect backdrop for the new iPhone 11 commercial: a continuous, five-hour-long shot exploring the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.4 Watching it, or letting it play in the background, checking in and out, letting its muffled sound effects fill my apartment, I am struck by a sense of loneliness. Museums are where we come together with other people, where we share a ritual around art. No long shot will replace that. But at a time of social isolation, public programing around art can provide a way of coming together. MoMA PS1 organized a day of livestreams to replace its VW Sunday Sessions program. E-flux video & films are cooperating with several institutions to organize online screenings and other events. Both of these, like the Biennale of Sydney, respond to the work artists and institutions are already doing in an attempt to translate them to a viable space at this time. It could be a moment not only to think about how we can see art online, but also about how our digital lives have changed the way we view and make art.

A review of the online iteration of the biennale will be published on art-agenda at the end of April.

Hollie Jones, “6 Now-Closed Exhibitions That You Can Still Explore In Street View”, Google Arts & Culture https://artsandculture.google.com/story/6-now-closed-exhibitions-that-you-can-still-explore-in-street-view/AgJS_V6WxTWzKw.

“Inside Brazil’s Museu Nacional,” Google Arts and Culture https://artsandculture.google.com/project/museu-nacional-brasil. I am very grateful to artist Ofri Cnaani for the research she shared with me about this.

Axinya Gog, “A one-take journey through Russia’s iconic Hermitage museum | Shot on iPhone 11 Pro” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=49YeFsx1rIw.