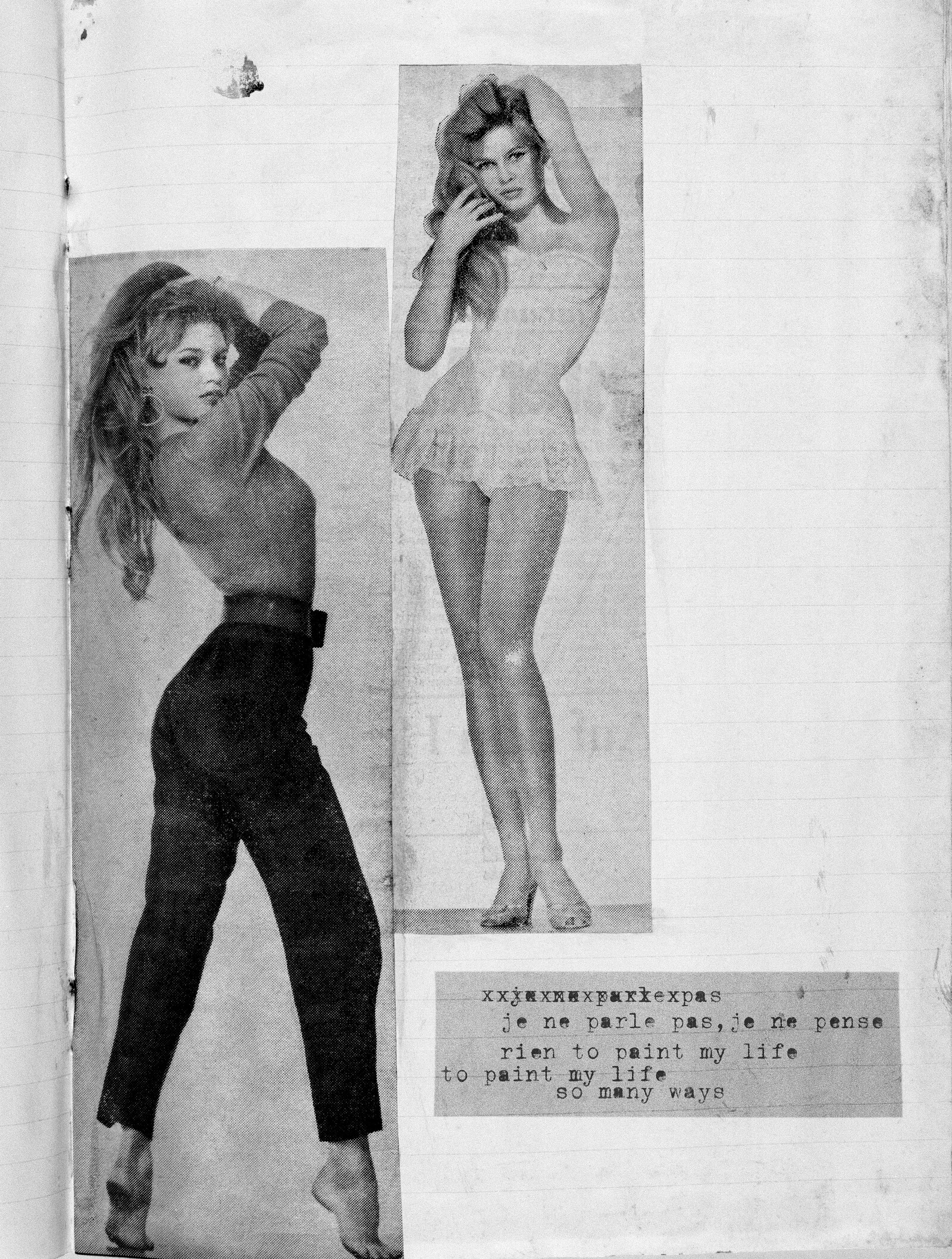

Astrid Klein’s photowork Untitled (Je ne parle pas,…) (1979) presents two cut-out images of Brigitte Bardot—posing in a baby doll dress and, again, coquettishly looking back over her shoulder. In broken, typewritten French and English are the words “je ne parle pas, je ne pense rien” (“I don’t speak, I don’t think”) and “to paint my life, to paint my life, so many ways.” It’s a fitting prelude to this exhibition, which is something of a house of mirrors. Trapped behind the museum glass, like sexy cats in apartment windows, large photographic works fill the walls, each featuring a beautiful woman while slyly reflecting the viewer. In Untitled (la sans couleur…) (1979), a reclining woman awkwardly turns her head to look at me with an enigmatic smile. Loosely draped in a sheet on an unmade bed in the dark, she is a body in waiting. These gazes are not exactly inviting; if anything, they somehow lack emotion, as the title reflects: “masks without color.” But there is something cool, even powerful, about their magnetic resignation. Like several in the show, the image is arranged with visible marker framing and taped sections, giving the impression that this composition sets the stage for something else.

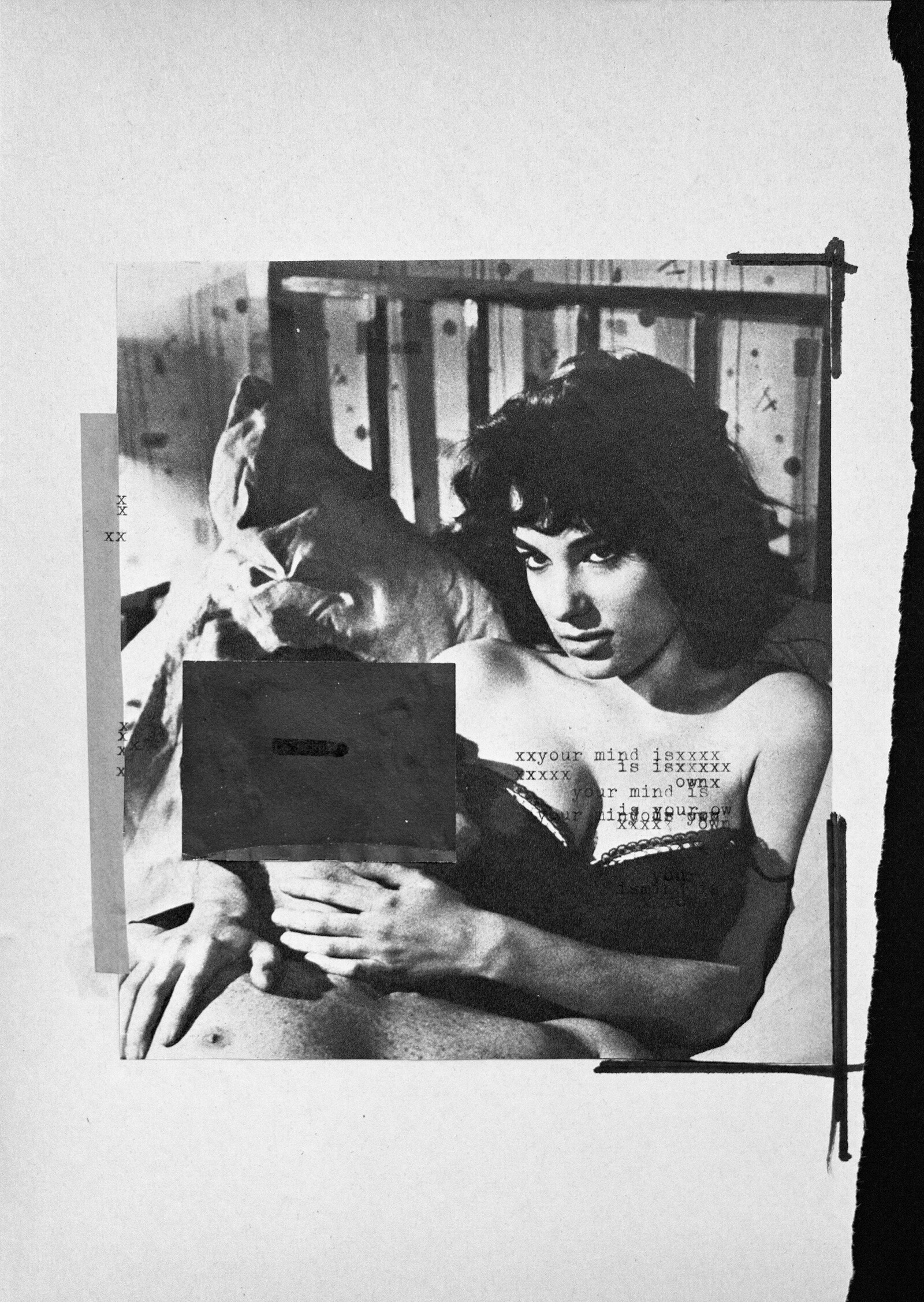

In the main space, the exhibition consists of a series of large “photoworks”, all from 1979, and early, mostly black-and-white photo-collages, which preceded Klein’s later “white paintings” phase (1988–93): these are hung in the side room near the front. This introductory survey is the first in New York for the German photo-conceptualist veteran, whose persistent inquiry into the subjectivities of the cinematic femme figure have long articulated and driven much wider discourses around agency, power, and the reproduction of images. Encountering these works in person, I’m pleasantly surprised at their scale: Untitled (your mind is your own) towers over me. In the composed image, taken from a film still, Bernadette Lafont cradles a bare-chested man, whose head is obscured by a cut-out shape. Her glance is just about to turn towards the viewer with a slight sneer. Typewritten words float over her breasts: “your mind is your ownxxxx’’ reads like a personal mantra, which seems to evoke further internal monologues. “Powerless.. rebellious.. xxpowerlessrebelliousxxx,” thinks the woman in Untitled (powerless…) while looking sullenly towards the ground. “Leave no memories,” pleads another. In Untitled (transcendental homeless) the figure rests her head in her hands, appearing exasperated. A redacted newspaper byline offers an enigmatic explanation: “Revenge was offered to me by chance.”

Klein’s photoworks are simultaneously campy and subtle. They are framed in a way that speaks specifically to commercial presentation formats: pitches, mood-boards, and other displays of the last century, formats now little utilized, but which exist in the cultural imagination as a referential mechanism of production. These formats gesture to a time when a handful of popular icons dominated the public sphere. Now, celebrities of the past decade barely linger in the collective consciousness, much less the starlets of 1960s French New Wave cinema. Seen today, they read like sketches of a bygone era. It is difficult to say whether this serves the artist. On the one hand, some of the conceptual heft accompanying these particular figures is lifted, revealing the mechanism below to be a rather obvious nod to second-wave feminism. On the other, the shedding of that cultural significance and specificity to the French Femme ethos cracks their didactic mold and makes the images lighter, sharper, funnier—and, one might argue, more relevant than ever.

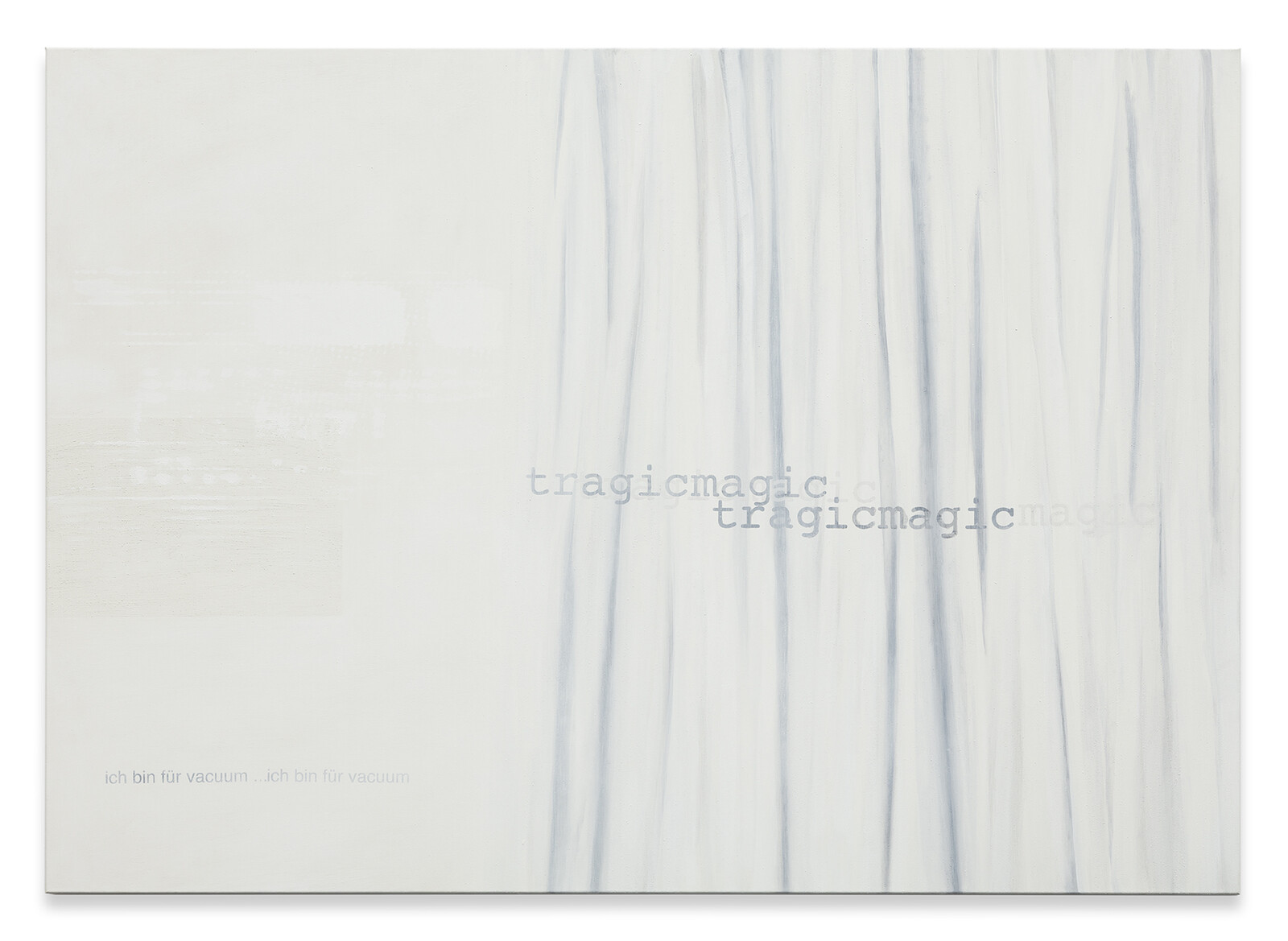

After all this, walking back to the end of the gallery to visit Klein’s white paintings feels a bit like rewinding the tape. In Untitled (tragicmagic), painted between 1988 and 1993, the same typewritten words prevail, this time with the double “tragicmagic” floating on top of a painted curtain-like apparition in a wink to realism and German picture-making. In the bottom left, the words “ich bin für vacuum” also appear twice, as if Klein is ironizing these works’ own apparent vacuity. The paintings have a sculptural quality to them, conceptually distended as they are, but they are not the stars of this show. If anything, they’re portals to the empty, guilty internal spaces where her photo collages settle; silver foil and alabaster paint both reveal and conceal my own searching gaze.