Earlier this year, I returned to my home state for the first time since the pandemic began. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) was hosting Nam June Paik’s first retrospective on the West Coast and, under the California sun, the Korean-American artist’s works seemed to couple the beauty of modern technology with just enough irony to stave off techno-determinism. It also prompted me to reflect on Paik’s status as a prophet of the idealism I had grown up with, and to consider how his work reads today, now that the hegemony of Silicon Valley’s IT corporations has come to pass.

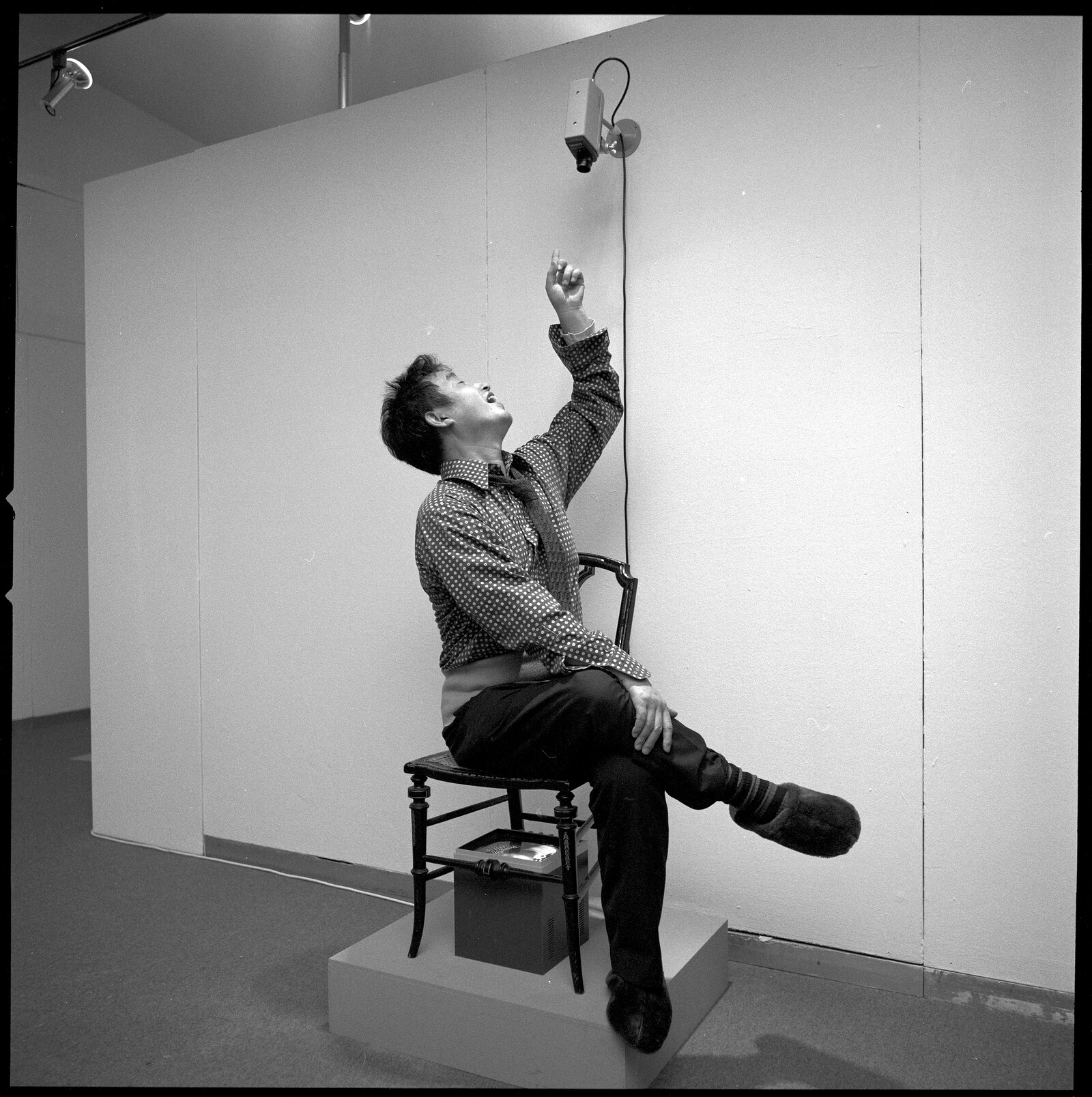

In Paik’s TV Buddha (1974), which opens the show, a black Buddha statue sits across from a white television set, behind which looms a video camera. The closed-circuit camera, of the kind that Paik often used in his work, captures both statue and passing viewers and projects them onto the TV screen. Iconic and serene, the statue’s pose is reflected in a two-dimensional circuitous feed that seems to mimic Silicon Valley’s romanticized Zen Buddhism-lite. This “Buddhism” has replaced Protestantism as a catch-all for many Bay Area-dwellers looking for a spiritual supplement to the region’s hyper-corporate culture, as evidenced by the numerous think pieces written about Steve Jobs’ relationship with Buddhist monk Kobun Chino Otogawa and how Apple’s minimalist aesthetic cues might derive from the religion’s incentive to “simplify.” It’s unclear what Paik, a practicing Buddhist, would have thought of the profit-motivated aestheticization of his spiritual beliefs, but the East-meets-West TV Buddha condemns neither technology, spiritualism, nor the gallery-goers who witness their meeting.

I was raised in the Bay Area, in proximity to telecommunications’ advancements, extraordinary wealth, and an easygoing culture that, in the nineties and early aughts, appeared benevolent amidst the extreme economic prosperity and social stability spearheaded by Silicon Valley. The Californian Ideology—to borrow the title of the 1995 essay by Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron—was a mixture of faux-sixties counterculture and libertarianism, combined with a fanatical belief in NGO techno-utopianism as the solution to social woes. This tug of war between technological progress on the one hand, and the legacy of the hippy movement on the other, results in what now seems to me stagnation: a conflict between past and future that immobilizes California in an inescapable present, which its residents mistake for peace. In this context, TV Buddha feels fittingly ambiguous: the curve of the Buddha’s head mimics the curve of the television screen, just as the statue’s meditative pose is reflected back at itself either ironically or sincerely, depending on the moods of passersby.

One Candle (also known as Candle TV, 2004), also on show in the Paik retrospective, plays with the transition between 3D materiality and the image by placing a live, burning candle inside a hollowed-out television set. The light of the flame is in contradistinction to the stream of electrons within the cathode ray tubes that normally powered TVs at that time. At first glance the TV looks defeated, a skinned, emptied vigil for bygone technologies. Closer inspection reveals a continuity between the candle and the cathode ray, the latter a descendant of the former. An irreverent monument to the history of technology, the discarded and broken appearance of One Candle conjures the past as a collection of wreckage piling up at the feet of Walter Benjamin’s angel of history. In Paik’s version, we are not propelled blindly away from the debris of the past by technological progress, but instead trace its lineage mournfully, knowing we can never move backwards through time.

In the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, stone-faced guards herd viewers of Michelangelo’s sweeping frescos quickly through the space. Photos are not allowed; neither is lingering to stare at the vaulting ceilings or raising one’s voice in the hallowed space. Paik’s (per)version, a large installation projecting overlapping videos and soundtracks onto the high ceilings of SFMOMA’s gallery titled Sistine Chapel (1993), challenges viewers to loiter. In a 1903 essay, the sociologist Georg Simmel suggested that the noise of cities prompted people to develop a “protective organ,” creating the solipsistic urbanites of bourgeois culture, while Luigi Russolo’s The Art of Noises (1913) proposed that a new form of music was necessary for listeners used to the speed and dissonance of the urban soundscape. Along with his fellow members of Fluxus, Paik sought to advance these ideas by embracing the cacophony of post-industrial modernity.

Like Michelangelo’s original, Paik’s piece takes the audience through the spiritual journey of humanity from creation to redemption. Overriding the pure origin myth central to The Creation of Adam (ca. 1512), Paik posits an illegitimate, pluralist Adam who creates, and subsequently destroys, himself. Spiritual tranquility or attempts at metaphysical meaning-making are impossible amid the sheer sensation of the work. Viewers are presented with a purely sensible body, unfolding all at once with gore, lust, laughter, and death. The videos depict bits and pieces of works shown in earlier galleries, including Guadalcanal Requiem (1977/79), a collaboration between Paik and performance artist Charlotte Moorman in which the latter army-crawls along the titular beach with a cello strapped to her back, intercut with archival footage of the battle that occurred on the beach during World War II.

Paik’s intention may have been to show how contemporary technology can usher in a new Renaissance, one that might make possible new human communities. Yet a twenty-first-century viewing points to the wreckage of the glorious techno-rebirth we were promised by the corporate giants in Silicon Valley. Perhaps nowhere is Paik’s tender relationship with the moving image more visible than in the installation TV Garden (1974–77/2002), recast in the light of twenty-first century San Francisco. Paik’s garden is a bizarrely beautiful series of television sets hidden in the foliage of live plants. The televisions flicker with the same video montage of quasi-erotic dance moves performed to a peppy soundtrack that envelopes the otherwise dark room. TV Garden’s absurd presentation of the coexistence of technology and nature is fantasy realized: televisions (or nowadays, computers) are as plentiful and easily harvested as produce; they come from the fecund soil of well-maintained cognitive labor and their glows provide enough light to maintain a healthy and fruitful environment.

Seeing Paik’s works made me nostalgic for avant-garde art and for the imagined California of my youth. It suggested that two seemingly opposing forces can be fused into harmony, be they nature and technology or capitalism and asceticism. But Paik, in prophetic fashion, includes a warning: both the tropicals and TV sets rest on the hard floor of the museum, neither fruitful nor fertile—a reminder, perhaps, of the extent to which contemporary technology relies upon unsustainable manufacturing processes and the depletion of natural resources. Paik’s work might have foreseen a future that in many ways came to pass, but he understood that it was grotesque as well as beautiful.