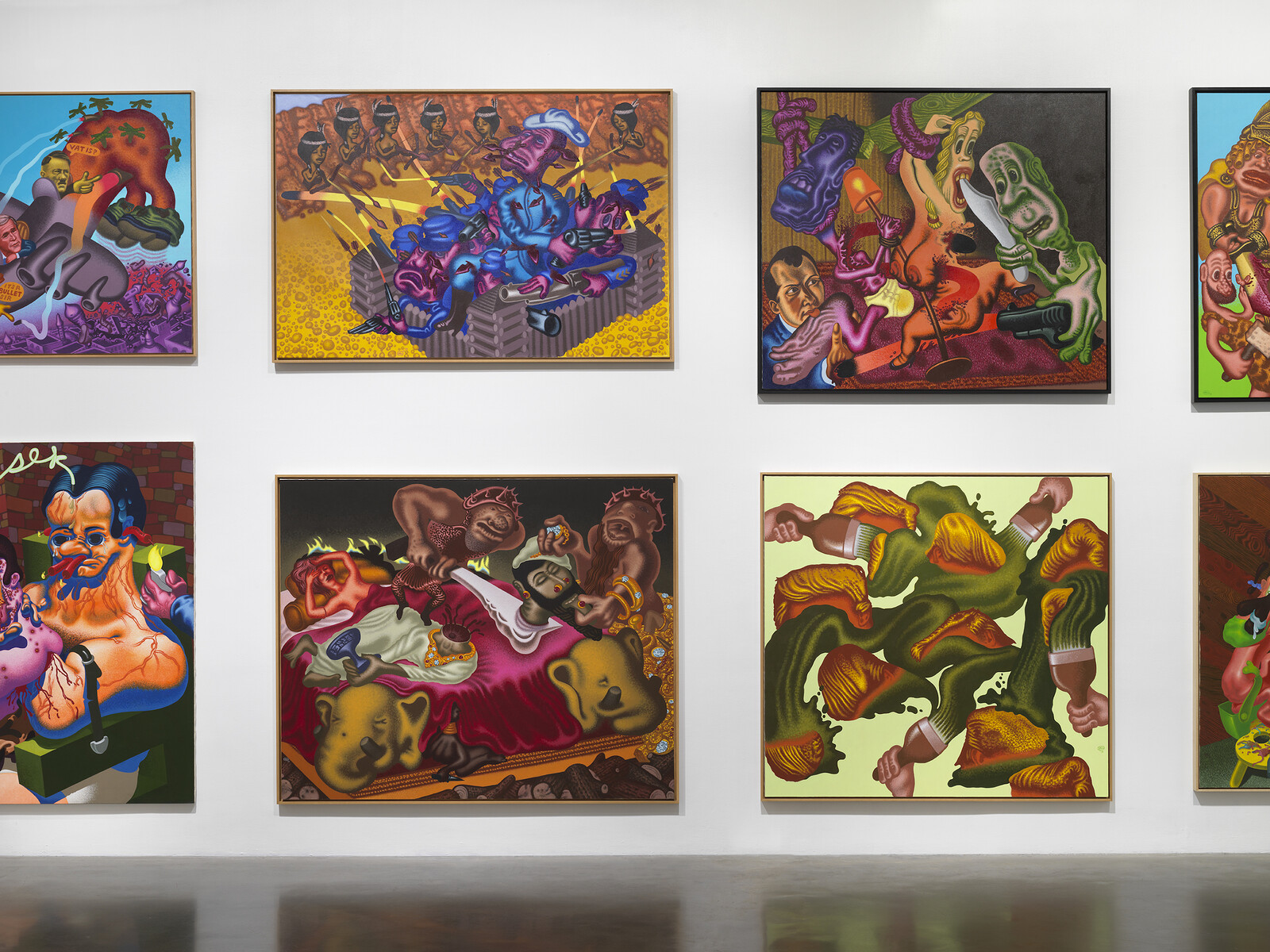

How much is too much, when it comes to the art of Peter Saul? How about: The big high box of the New Museum’s fourth-floor gallery stacked two-deep with more than two dozen large paintings in fluorescent hues? How about: Every gallery on the floor below packed with at least as many again, dating from 1960 to the present? How about: Three paintings that feature Donald Trump? Seven of electric chairs? Countless more figures with bullet-holes spewing glossy gouts of blood? A dog barfing onto the head of Rush Limbaugh, accompanied by a speech bubble that reads “BARF”? How about: One retrospective, only the second of the artist’s career, and his first in New York?

I thought I was a fan of Peter Saul, but “Crime and Punishment,” the five-decade retrospective curated by Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari, left me numb. Really, there is no other way to feel after seeing this much of Saul’s work, which trades in violent mayhem, visual noise, muscular kinesis, compositional derangement and—increasingly since the mid-1960s—hard-edged shapes rendered in bold and clashing colors.

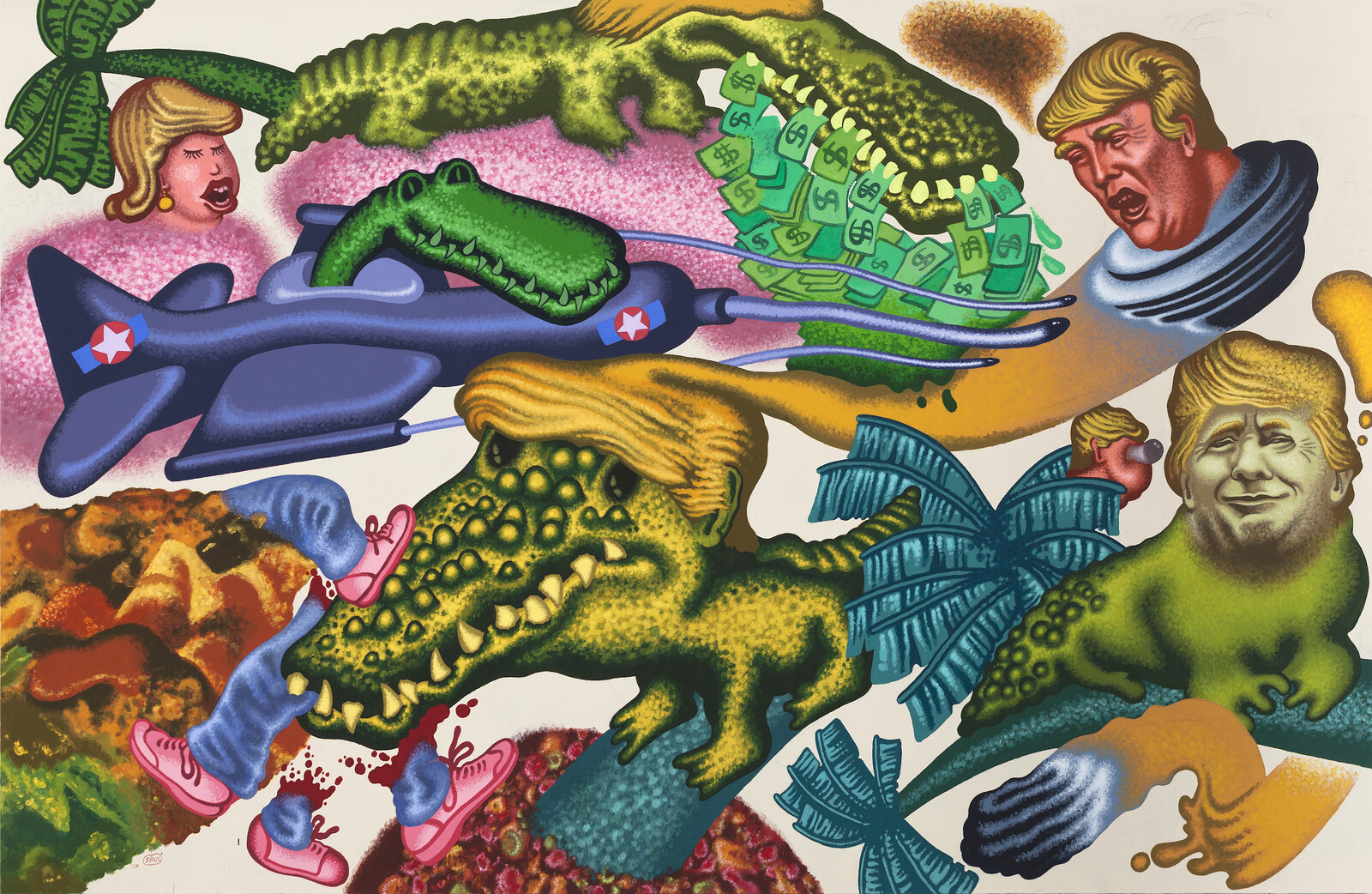

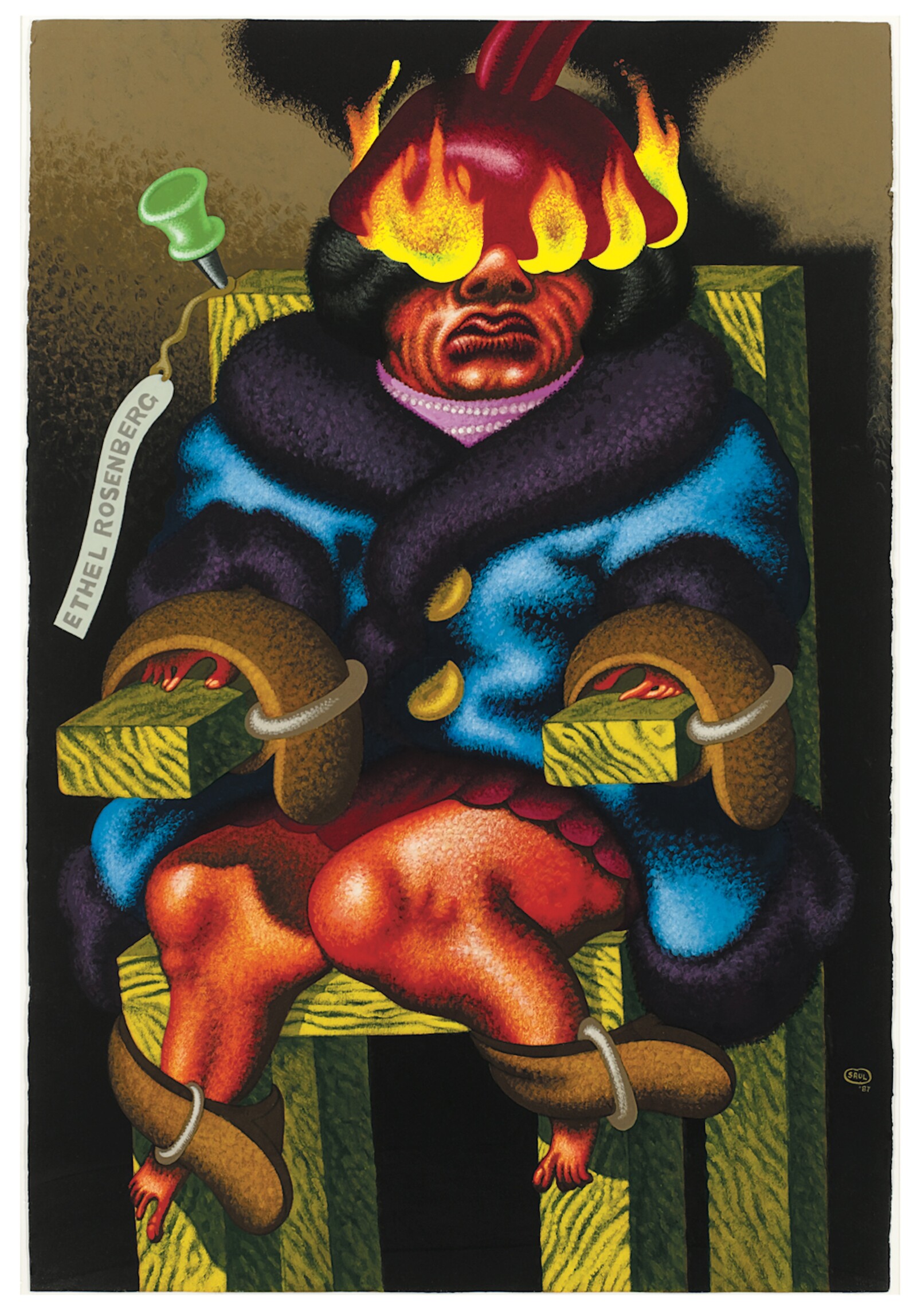

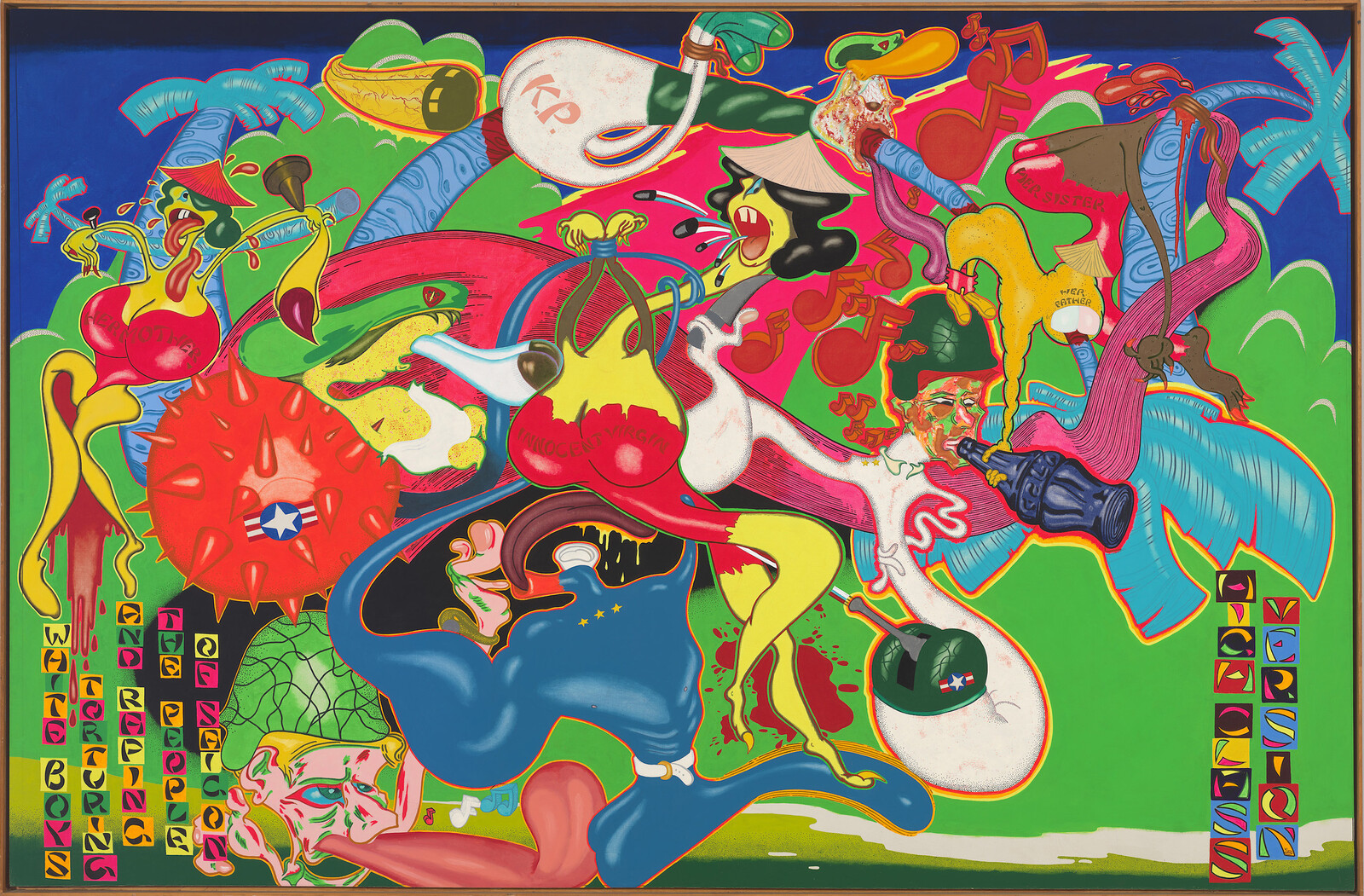

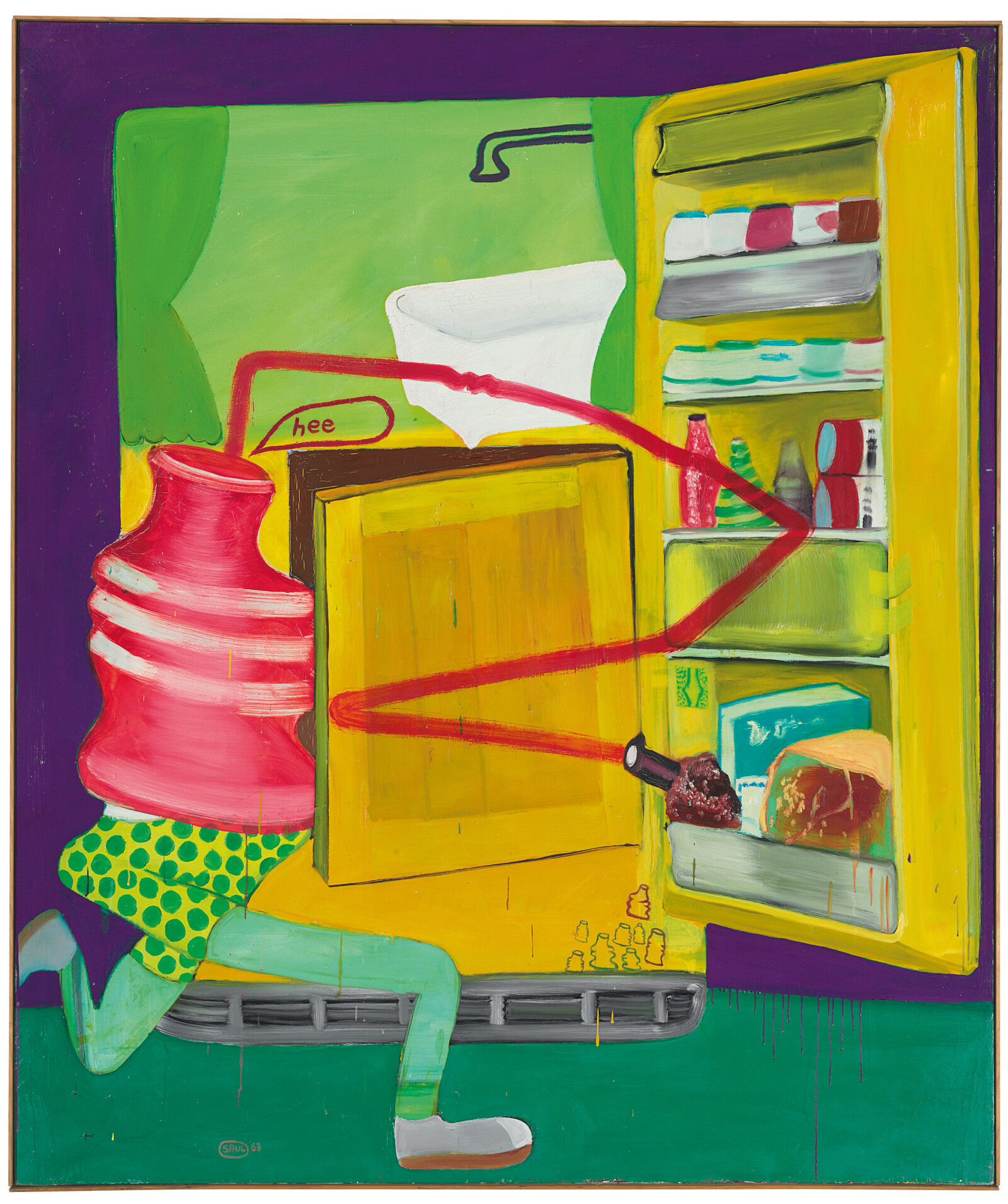

There is no question that Saul is a virtuoso technician, as he himself seems eager to demonstrate. His meticulous use of pointillism renders forms almost universally smooth and matte, no matter the subject. In Stupid Argument (2010–11), for example, faces, airplanes, a banana, and eruptions of colorful carbonated froth all share the same texture. This is just one solution to the rhetorical problem posed by his earliest “Ice Box” paintings, four of which are included here: how to make disparate elements cohere on a single canvas. Saul’s youthful style in the early 1960s anticipated the cartoon-influenced figuration of Philip Guston later that decade; his oils dripped and spattered, and his surfaces tended towards the smeary. Soon, domestic tableaux gave way to topical narrative works such as Man in Electric Chair (1964) and paintings lambasting the war in Vietnam. As Saul’s political views hardened, so did his edges.

Despite the disorder of his tangled, de-centered compositions, they are held taut by forces that push and pull across the image. The pictorial stage-set for Saul’s theatre of the abhorrent is relatively shallow; the cartoonish action pings back and forth across the canvas. Bullets fly hither and thither, not necessarily in straight lines. Fingers, fists, arms, legs, and feet extend from rubbery bodies to lodge themselves in others’ eyes, mouths, and worse. Scenography, which most of the time seems almost superfluous, serves mainly to direct the viewer’s gaze with sweeps of discordant background color.

Why is fine technique so important to Saul? Maybe because by elevating the basest of subjects, he simultaneously makes them easier to look at and harder to think about. Take, for example, the chainsaw, in Oedipus Jr. (1983), that has ripped through the protagonist’s crotch. The coral filigree of blood that borders the wound is mesmerizing, though appalling, and an irresistible distraction from the tiny tag on the saw reading “FIRST WIFE.” It’s a crummy joke, exquisitely delivered. Technical mastery is itself a kind of lowbrow attribute, a blue-collar gratification—as was especially the case around the time when Saul was making his name as a painter, in the 1960s and ’70s. His formative influences, which included not only MAD magazine and underground comix but also painters like Paul Cadmus and George Tooker, share deft craftsmanship with an unaffected populist tone.

Throughout his career, Saul has prized freedom above all else. He has steered determinedly free of art world conventions, free of what he sees as its aesthetic strictures, free of art-historical movements, free of social mores and niceties. But today, the notion of freedom no longer has the democratic (or even libertine) air that it once did. These days, the people who argue most loudly for freedom of speech—freedom to transgress, freedom to offend—are often those whose views are considered most abhorrent by the majority. The question of how far society should tolerate those individuals is, perhaps, the central ethical, political, and philosophical dilemma of our time.

Personally, I would not deny Saul the freedom to paint women, for instance, as balloon-breasted victims of rape and defilement, or Vietnamese people in conical hats, or Grenadian men as identically afroed silhouettes, or even US soldiers as python-donged meatheads. But the pantomime offense wears thin after a while. Saul’s artistic strategy is to position himself as the lowest of the low, then to act out in order to provoke outrage in his audience. But he presumes a lot about his viewers: not only that they will detect the irony, that they will be on the joke and share his views, but that they will ultimately be people rather similar to himself. It is hard to imagine a Vietnamese person drawing much solace or satisfaction from a painting like Saigon (1967), in which “INNOCENT VIRGIN” (labelled across her giant breasts) is shot between her legs by a US Army mortar. These are American paintings, about America, by an American, for Americans. Their too-muchness is the very essence of their identity, but it also circumscribes their limits.