About 15 minutes’ drive from the mirrored towers of downtown Los Angeles, a shady canyon throngs with oaks, willows, sycamores, and cottonwoods. Treefrog tadpoles wriggle in the creek. Snakes hunt among the rocks. Visitors to Hahamongna Watershed Park, named after the Tongvan village that once existed there, also cannot miss the adjacent white buildings of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a giant research facility owned by NASA.

This discordant landscape, according to a text accompanying American Artist’s exhibition “Shaper of God,” was an inspiration to the science fiction author Octavia E. Butler, who set several of her novels in nearby Altadena and Pasadena, where she lived for much of her life. (Butler died in 2006, at 58.) The exhibition, dominated by recreations of urban street furniture, is really a single installation made from several semi-autonomous artworks. Its enigmatic title derives from a verse in the fictional religious text The Books of the Living, quoted in Butler’s nightmarish futurist novel Parable of the Sower (1993): “We do not worship God. / We perceive and attend God. / We learn from God. / With forethought and work, / We shape God.”

Among other themes, Parable of the Sower is about self-determination in the face of dehumanizing circumstances. American Artist (who changed their name in 2013, and who uses non-binary pronouns) was also born in the area, and, like Butler, attended the local John Muir High School, though decades later. Both are African American; both use their work to explore and expose the ways that systems of power—technological, cultural, societal—exert themselves on the people who must live within them.

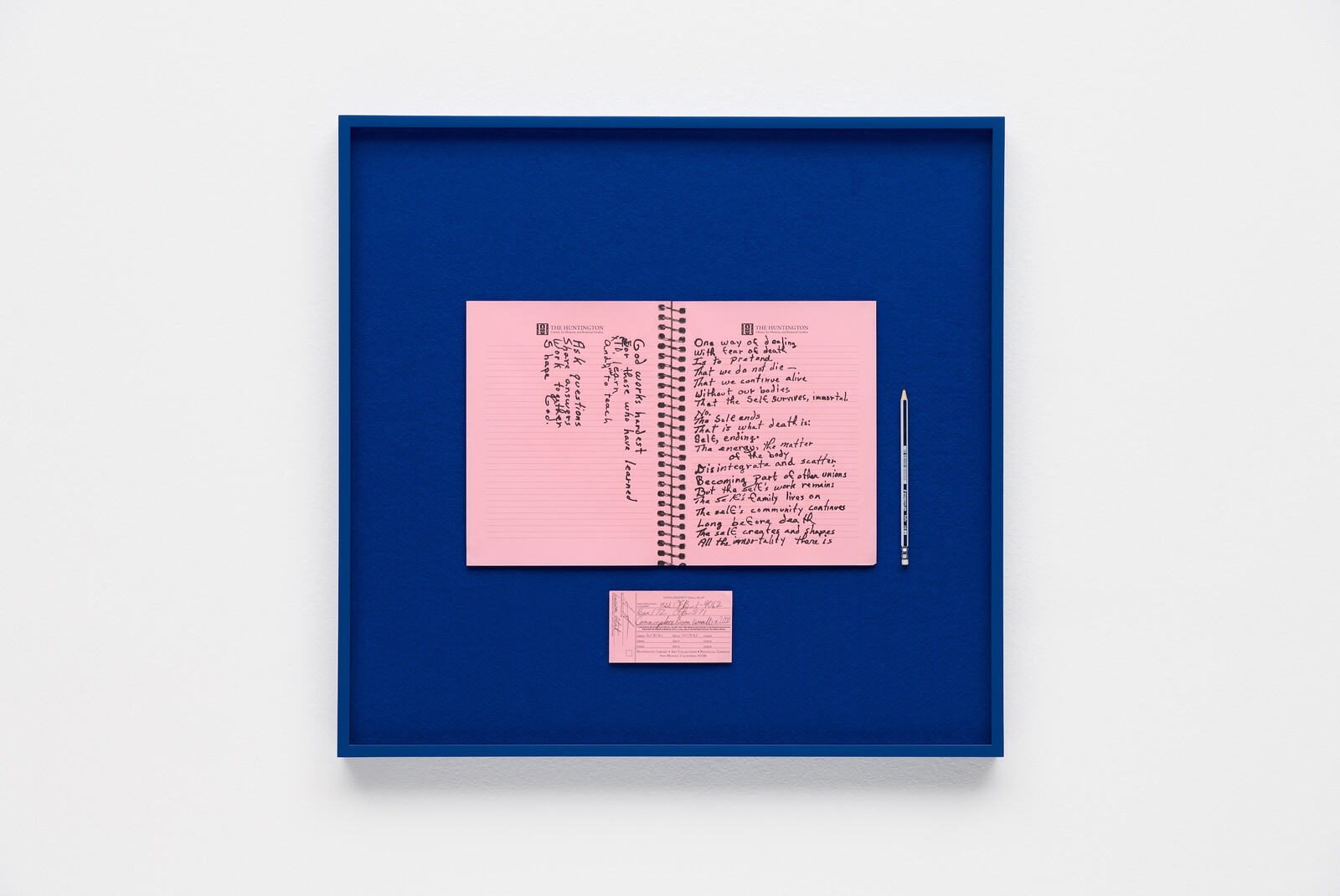

“Shaper of God” is so thick with reference, both to historical and biographical fact and to Butler’s speculative fiction, that it is tricky to parse what contextual information is essential, what is non-essential but enlightening, and what is superfluous. This challenge may have arisen partly due to the evolution of the project: as a grantee of LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab, Artist began their research at the Huntington Library in San Marino, where Butler’s vast archive is kept. Leafing through the minutiae of her life’s effects must have been overwhelming. On the walls at REDCAT, blue frames contain pink sheets of regulation Huntington paper, onto which items from the archive have been copied, in pencil, including a bus timetable, personal reminiscences, lists, notes for stories. Different hands are in evidence: Butler’s looping script, and a more erratic handwriting that apparently belonged to her mother. (“When I was a little girl my parents was very poor. Worked night and day. There was no school for Blacks.”) Alongside are facsimiles of the request slips that Artist filled out, and fresh Staedtler pencils.

These pieces are slow to unpack. We have mostly to infer what we are looking at, and the writing is only intermittently legible, as is the narrative of their fabrication—they seem too perfect to have been traced on-site, so their artifactual presentation feels a little hokey. But folded within them are poignant analyses of systems of informational preservation and control: the jealous protection of Butler’s effects by a historically white institution, and its mediation of their dissemination by a Black contemporary artist.

Fittingly, a high wall bisects the gallery, bristling with coiled razor wire. At its center, a battered metal gate stands ajar. Robledo Community Wall (Olamina cul-de-sac) (all works 2022) is a literal manifestation of the protective wall that surrounds the fictional settlement of Robledo in Parable of the Sower, and a literal symbol of exclusion and control, garnished with the threat of violence. Within “Shaper of God,” it steers the exhibition away from the archive and towards stagecraft; viewers are now cast as actors in a theatrical mise-en-scène. Artist invites us to rest on a bench beside a bus stop sign modeled after the vintage signage Butler would have waited at when she rode the bus (she did not drive). A second sign is placed on the other side of the wall; titled To Acorn (1984) and To Acorn (1968), respectively, the sculptures refer both to the new community established at the end of Parable of the Sower (in the year 2027), and to earlier, formative periods in Butler’s life before she began writing the book.

In “Shaper of God” we ricochet through time and space, reality and fiction. Yannis Window is a sliding glass wall based on a description in Parable of an improvised projection screen. Sitting on the bench, viewers can watch Artist’s grainy video The Arroyo Seco, which is scored and narrated like a 1980s’ public access television documentary, about the pre-history and speculative future of the park. The film claims to be a production of “The City of Robledo Historical Society,” but we know that to be a fiction within a fiction—Artist’s imagining of a time of prosperity before the devastation described in Butler’s novel. That reading is complicated, however, by a digression about the racial segregation of local high schools—John Muir and the newer La Cañada High School, which drew white students away from John Muir in the 1970s. “The Watershed served as the unsuspecting backdrop to political distributions that have characterized the last decade of a racially motivated civil unrest within the nation,” the narrator informs us—a line that encompasses, in its ambiguity, both the real context of the contemporary United States and Butler’s imagined version; the unrest of 2020 as well as that which overtook Los Angeles in the 1990s. (Incidentally, unmentioned in the film is the name of another John Muir alumnus: Rodney King.)

Science fiction is, by its nature, an often-patchy hybrid of past and future, fantasy and reality. “Shaper of God,” despite its immaculate production values, can feel patchy too. Its all-too-familiar forms (the framed archival document, the faux-documentary, the 1:1 scale replica) groan under the weight of information they are tasked with carrying. As such, they may be bound to fail. But collectively, they crackle too with ambition and sparked connections. Given the scope of the project on which American Artist is embarking, its future looks promising.