The influence of translations of Taoist texts, including the I Ching and the Tao Te Ching, on early twentieth-century ecology in the West and its post-war cybernetic revival is well-known. According to the teachings of Lao Tzu and centuries of Taoist tradition, the Way is found in the encounter of differences: a managed equilibrium, or flow, between hand and plant, culture and nature.

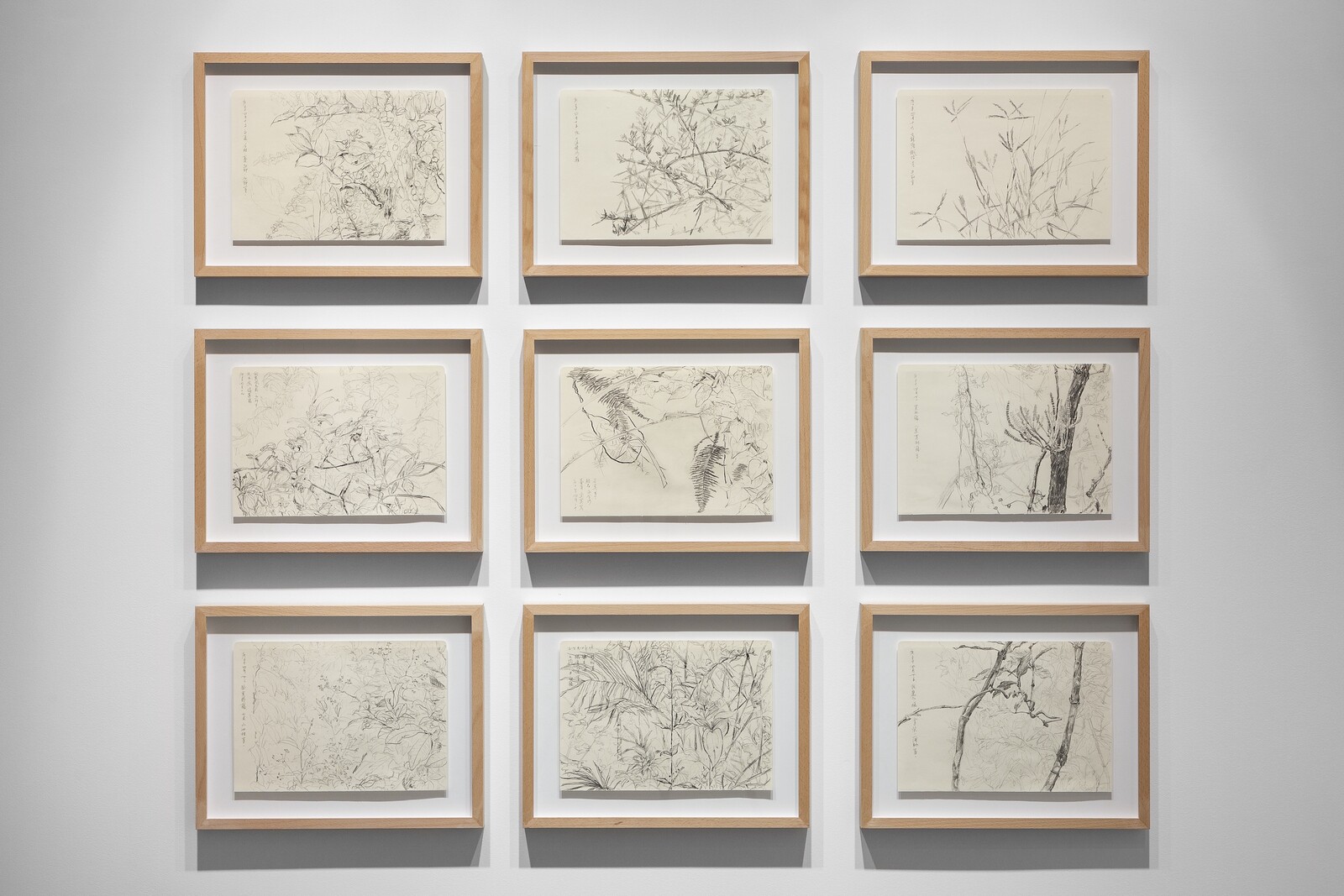

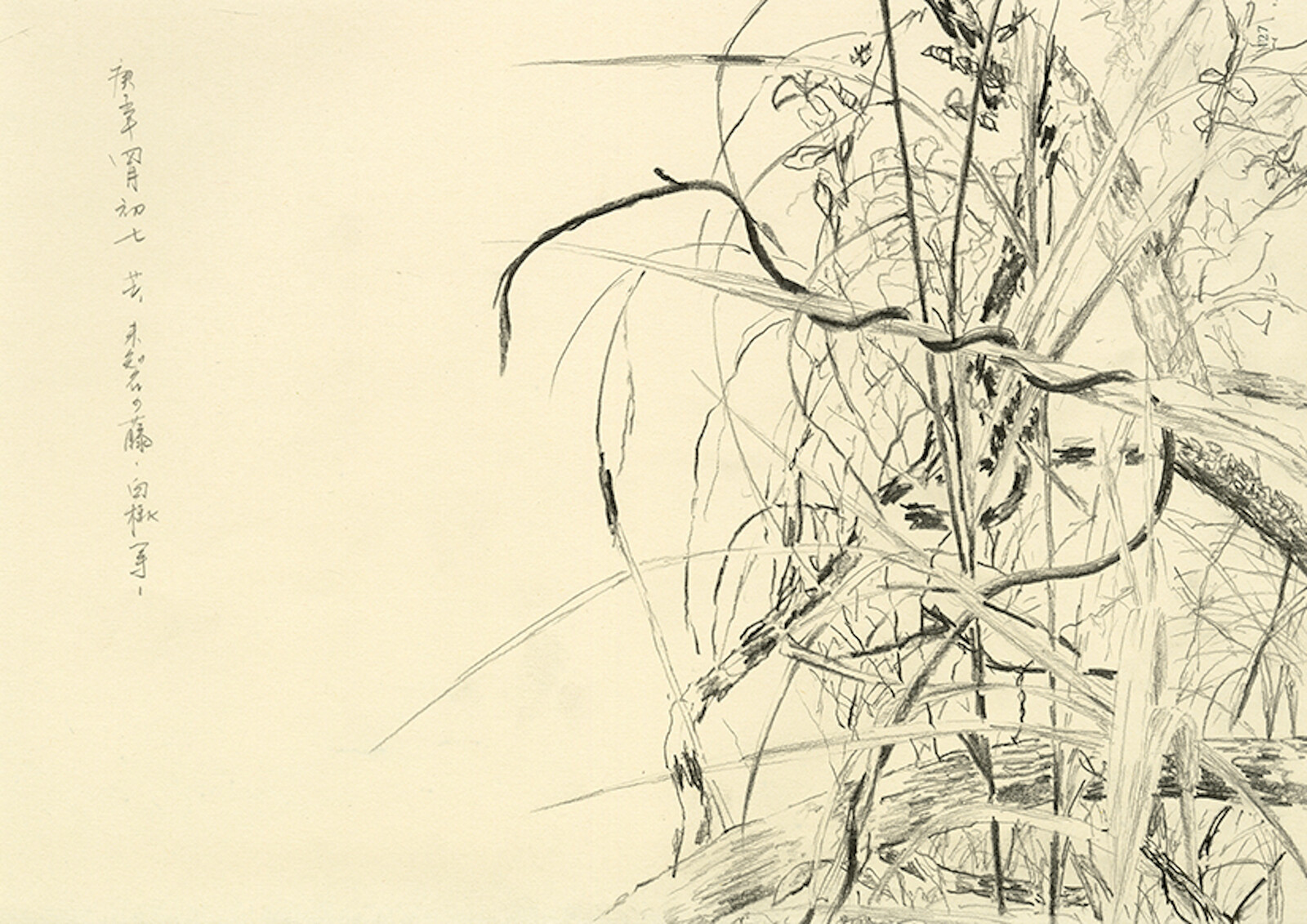

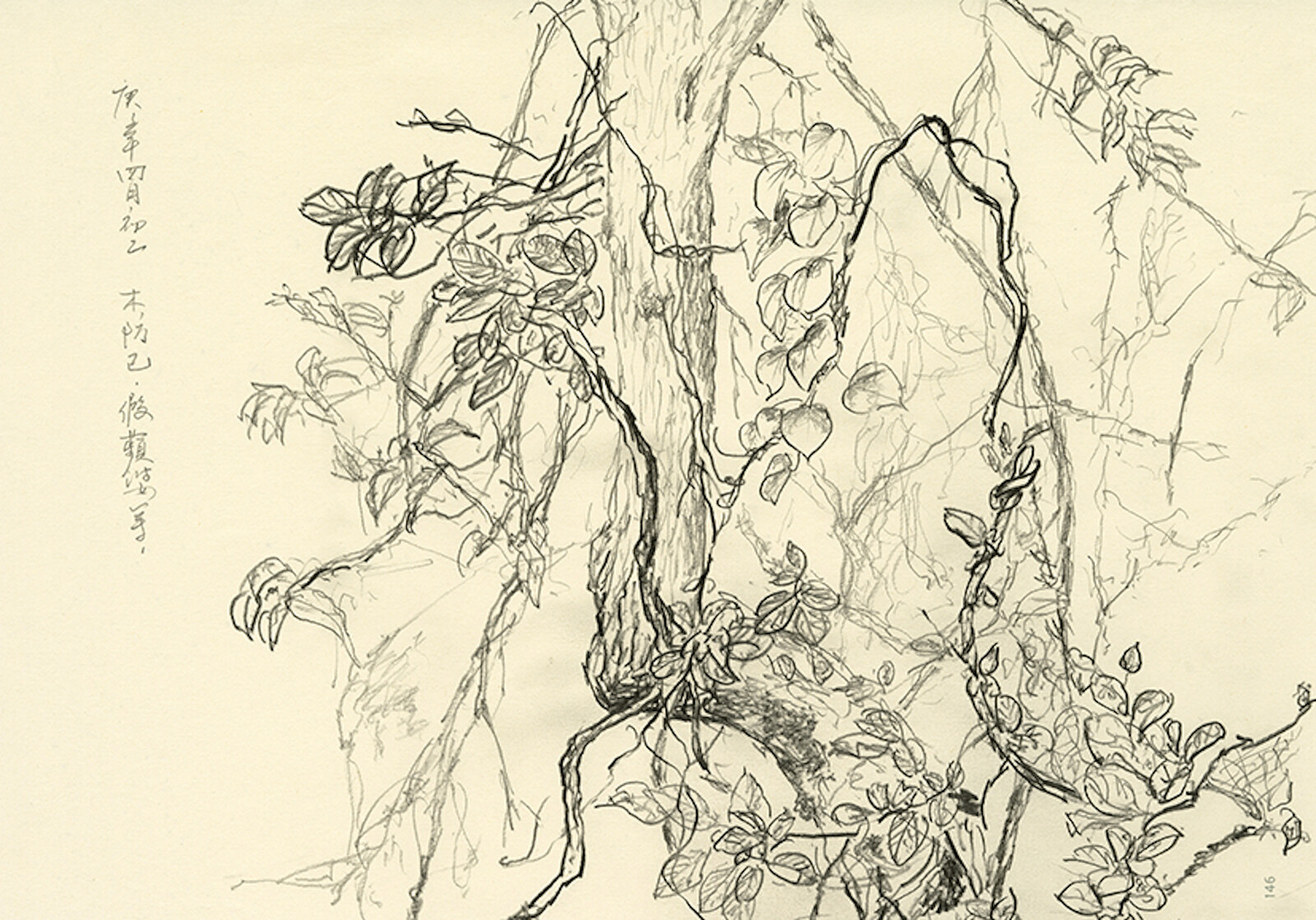

Zheng Bo’s practice often expresses this tension in ways that acknowledge the different ecological philosophies of East and West while queering the relations—and expectations—that humans have about plants. His first solo show in Portugal, at Kunsthalle Lissabon, includes two sets of works: “Drawing Life” (2020–ongoing), a new series of framed charcoal drawings depicting plants the artist found during his walks in Hong Kong’s Lantau Island, where he lives, during the Covid-19 pandemic; and “Pteridophilia” (2016–ongoing), a series of four videos in which naked men in a Taiwanese forest—in groups, in pairs, or alone—have sex with ferns by licking, biting, stroking, and rubbing them.

While the new drawings reflect on the tension between urban development and plant life, the four “Pteridophilia” videos, projected onto a gallery wall, broaden the meaning of queerness by engaging with ecosexuality, a term coined by former porn star Annie Sprinkle and artist Beth Stephens to refer to those for whom “the Earth is our lover,” rather than a resource to be exploited.1 Together, Bo’s works unpack queerness as practices and idiosyncrasies tied not only to human-bound identities, gender expression, or sexuality, but also to nature’s myriad ways of recombining and surviving beyond the norms and expectations imposed by humans.

The homoeroticism in “Pteridophilia” is evident in the camera’s luscious, desiring gaze, which focuses on the men’s muscular, athletic bodies, their contortions and pleasurable moans. Still, the sexual orientation of the men can only be guessed at: for what sort of orientation defines human desire for plants? As for the plants, their desires are even more of a supposition. The impossibility of knowing the plants’ intentions, not to mention consent, points to one possible response to the videos: a well-intentioned liberal moralism that judges such sexual impulses as violent. This is particularly tempting in Pteridophilia 2 (2018), in which a man with a hard-on fucks a large birds’ nest fern to the ground and eats the plant whole. Yet such criticism eschews the contradiction that, in judging these acts as violent towards the plants, it is the critic who seems to fall into animism (do plants have will?), overlooking their own taste for salads and greens, and ignoring the necessities of agricultural and garden life, such as slash-and-burn, crop rotation, and pruning. This is not how I react to Bo’s erotic videos.

While the sex is often explicit and penetrative, the overriding sense is of a full sensorial experience: human skin rubbing with plant skin, semen mixing with water droplets, and lips sliding on furry fern shoots. This is especially true of Pteridophilia 1 (2016), where the emphasis is on men contorting their slick bodies on the plants, rather than genital stimulation. Perhaps this is something plants, and ecosexuality, have to teach us humans: a non-genitalization of pleasure, and an awareness of the body as amorous, open, porous—queer. This could potentially save us from toxicity, bringing ecology from the forest to the bed.

Truth be told, watching the lengthy shots of “Pteridophilia” projected to the scale of the gallery’s walls while resting on a bean bag for half an hour left me with a sense of arousal (and an erection) rarely experienced in an art space. Whoever has fucked in the countryside and come on grass, tree, or shrub instead of bedsheets knows how thrilling the difference is, and may wonder how it might go the next time they find themselves alone out in nature. There is also something polyamorous about these scenes, something unbounded. The men rarely touch each other and are usually alone with their plants. But sometimes they help one another knot ferns around their cocks or share fiddleheads from mouth to mouth. Between the plants and the men is a multispecies collectivity, with the plants acting as mediators between human senses. Following the Tao, perhaps the ecosexuality Bo offers the viewer is simply another recombination of species, and of love, in the acknowledgement of differences. A rewiring of desire beyond egocentric pleasure. An ecological mobilization of sex.

Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle, “Ecosex Manifesto, Draft 1.0 of a Work in Progress,” Brooklyn Rail (September 2014) https://brooklynrail.org/2014/09/criticspage/ecosex-manifesto-draft-10-of-a-work-in-progress.