March 9–24, 2018

Expedition: “Spheric Oceans” led by Chus Martínez Participants: Julieta Aranda, Claudia Comte, Francesca von Habsburg, Eduardo Navarro, Ingo Niermann, Markus Reymann, Teresa Solar, Albert Serra

I decided to name this three-year cycle on artistic intelligence, philosophy, science, and nature the Spheric Ocean. The Ocean is spherical because it is not beside the earth nor below it, but all around it. Its form is not what our eyes see, or not only. Its reality cannot be separated nor told apart from anything else on the lived earth. Therefore it poses us a demand: the need for a philosophy to help us exercise the Ocean. It is difficult to describe what we are aiming for. I would say we are aiming for a philosophy more than anything else. It would be wrong to think that when we say “Ocean,” we are naming a “subject.” We could be as radical as stating that today, to say “Ocean” is to say “art.” Art without the burden of institutional life, without the ideological twists of cultural politics, art as a practice that belongs and should belong to the artists, art facing the urgency of socializing with all those who care about life. Or, in other words, to say “Ocean” is to replace the historical notion of the avant-garde with a code that is not determined by form and the invention of new gestures, but by an investigation of the substance of life, identifying this as the mission of art.

Day 1: March 12, Monday Latitude: 36° 50.56’ S Longitude: 174° 45.5’ E Swell: harbor

Observations Does a storm have a function? I could not find a single entry saying so. This is probably why we call them disasters, because they are closer to anger than to function. Satellite technology allows us to track them; we can see them through an app, forming, moving. The warm temperature of water fuels them, a cloud of moisture moves up from the surface of the Ocean creating a vacuum below. “New” air becomes moist and warm, rising as well, and the surrounding air swirls to take the place of the air that just joined the cloud: a whole system of dynamic energy and movement originates. It was a novel, a bestseller diary of a storm near the coast of Japan, written by George Steward, that helped to establish the naming of storms. That fictional storm was called Maria. This one, the one we are waiting for, is called Hola. The use of female names for storms disgusts me, but Hola also reveals our continuous insistence to civilizing nature. It is not a Spanish “Hola” but a Fiji “Hola.” Ho-la (jo-la) came after Fehi and Gita and the next big storm is going to be called Iris, and after Iris it will be Jo, and then Kala.

JULIETA ARANDA Waiting for the storm The anticipation of losing control, being placed dead center in the center of an environment that exceeds me in my attempts to define it. What is a storm? And what is a storm when coursing through one’s body? How do I shape-shift through water?

CLAUDIA COMTE Nature, art, music, buildings, human beings, creatures…everything is related to mathematics. If a true universal language exists, it is most likely to be expressed in mathematics, geometry, energy patterns, and frequencies. All nature’s works have a mathematical logic and their patterns are limitless. Everything starts with a perfect circle, the sun. The magic proportions of the golden section are often found in the spiral of nature’s desires. The rules are always the same. “Everything is arranged according to number and mathematical shape.” —Pythagoras

INGO NIERMANN The reinvention of the sock Ingo swam ashore and forgot to ask the other expedition members, who went by dinghy, to bring his shoes. When the group went for a hike on a gravel path, all that Ingo had to protect his feet was a pair of blue Uniqlo cotton socks. The socks did an amazing job: The gravel ached Ingo‘s feet and he made quite an effort not to step into any bigger goolie (the colloquial term in New Zealand for a stone or pebble) but even after an hour of walking his feet didn’t get injured and didn’t redden. The moment he stopped walking all pain disappeared. Even back in the salt water his feet were just fine. The socks also didn’t have any apparent damage.

Ingo was so impressed that his first research on the expedition didn’t address the ocean but the history of the sock. The oldest intact knitted (or to be more precise: naalbinded) socks are from 300 to 500 AD and were discovered in Egypt. The tangerine-colored pair has split toes for use with sandals and is meant to be tied at the top with little integrated ribbons. Long before, people wrapped their feet in different materials, like leather, felt, or fabric (foot-wraps) before putting on their shoes or sandals but there’s no knowledge of the existence of proper socks before the second century AD in Rome.

Strangely, the word sock and its numerous European variations have their origin not in the Latin word for sock—udone—but in the Latin soccus, a slipper with a thin sole that was originally reserved for comic actors. Tragic actors would wear the cothurnus (buskin), a high boot with up to five-inch-thick soles, to elevate themselves above the other actors and to make their steps more weighted. Socci would make comic actors appear relatively small and light-footed. Cothurnus became a synonym for tragedy, soccus a synonym for comedy.

It was only in the third century AD that the Romans, in the beginning mainly women, started wearing socci in normal life. The popularization of socci goes hand in hand with the decline of the Roman Empire. Things started getting soft.

But how to get from the soccus to the sock? Historians don’t seem to really care. Language is just too random, so why bother? But then again, why not? Why bother about every tiny interstage of natural evolution and not of such an essential element of contemporary clothing? Ingo develops three theories.

Theory 1: As socci were only convenient indoors, the next consequent step in the Romans’ softification was to replace socci with just as lavishly decorated socks, eventually with a leather sole. The design of the latter can still be found in certain contemporary house shoes like the alpine Hüttenschuh and in baby shoes.

Theory 2: Romans started to wear sturdier sandals on top of their socci when going outdoors. As this was not too comfortable, they replaced the socci with udones just as lavishly decorated—therefore still calling them socci.

Theory 3: Socks got reintroduced in the Middle Ages, still hundreds of years before the invention of the knitting machine in 1589, and became a brightly colored status symbol of the nobility, covering the lower part of trousers. As these garments were lavishly decorated like socci, Europeans started calling them socke, socka, sokkur, or sok.

All three explanations root the name of the sock in its decorative function. Today, we experience a certain renaissance of this function (pushed by brands like Happy Socks) while at the same time there is the even bigger fashion trend of the no-show socks. What both, seemingly opposite, trends have in common is an urge to distract from the functionality of the sock—and thereby the underlying weaknesses of our feet: they sweat (up to 120 milliliters of perspiration a day), they get easily cold (even in shoes), and they need protection from what is supposed to protect them (shoes). There seems to be the need of a rebrand to openly embrace the basic qualities of socks.

A solution is already underway: the reinvention of the sock, similar to Ingo’s experience, as an outdoor shoe. A couple of years ago, the sneaker industry was taken aback by research on the problematic effects of all-too-cushioned running. While purists pleaded for barefoot running, the sneaker industry was quick in inventing ever leaner, more flexible, and sockish shoes like Vibram FiveFingers, Nike Free, or Adidas NMD City Sock, it was only a matter of time until some company would launch an actual sock for running. Last year, a Kickstarter campaign for Skinners, stretchy synthetic socks with a thin rubber ground, generated more than $600,000 (aiming at only $10,000), and they are now for sale for just over $30. The only problem: they look and feel utterly ugly.

What could help is a DIY movement to create your own outdoor socks: take whatever pair you like and paint it with hot rubber (color by choice) on the ground. Alternatively, you could fill your socks with an arch support or, more naturally, as expedition member Eduardo did halfway through Ingo’s journey, a couple of big strong leaves. They smell good and might even be a form of skin care.

Sock shoes—short: sockoes—might not last long but a ragged pair can make a great souvenir. Your collected sockoes of several years fit into a single drawer or decorate a wall. Very special sockoes might be stuffed or framed.

MARKUS REYMANN While waiting for the storm to pass and the expedition to begin, walnuts were found or recovered in the two largest cultural institutions in Auckland. Technically, a walnut is the seed of a drupe, thus not a true botanical nut.

Day 2: March 13, Tuesday Latitude: 36° 47.21’ S Longitude: 175° 09.6’ E Swell: harbor

Observations Is the Ocean an art space? Funny enough, the question seems to imply the total culturalization of the Oceans: seeing all the creatures and plants as artworks, their submerged environments as their monumental container…. No, this is not what my question implies. If the DNA of our cultural institutions is history, through the conservation of artifacts, it seems possible to imagine that a new art institution, the Ocean, could exist on the premise of the conservation of life. You could now say that this image is just a metaphor, a poetic gesture, but I will state that it is crucial to insist, as long as it may take—decades, centuries even—in the literalness of thinking that the new models for culture will not originate in culture, that the best way to challenge our imagination of space is in a space produced by salt water. I think of the radical abandonment of the straight line, of the immense challenge technology presents us with, when it comes to processing information, and another question appears: How many waves are in the Ocean? All this water has a materiality, and we have been describing it formally for centuries. We have been creating analogies in order to relate the domain of culture and the world of the waves. People, charts, machines, technology, all what records the Ocean is oriented to capture it, to transform natural facts into historical ones. I do not quite know where I am going with all of this right now, but I feel an urgency to be able to sketch a theory capable of rendering the importance of introducing the Ocean within new regulatory principles to conceive experience anew, a space of dramaturgy anew, a practice anew, the connectivity among the material and the immaterial anew. This seems a surreal exercise. The world of art is still too dependent on “interpreting the sea” as a site for the extension of land-based activities: shipping, colonial travel, warfare, and communication, including networked submarine cables. And the work of the sea seems in no need for the world of art, but I feel my intuition is not crazy, that if we have been orienting our form of life around the principles of the industry, of production, of capital, there is hope that we could do a similar thing around biological life.

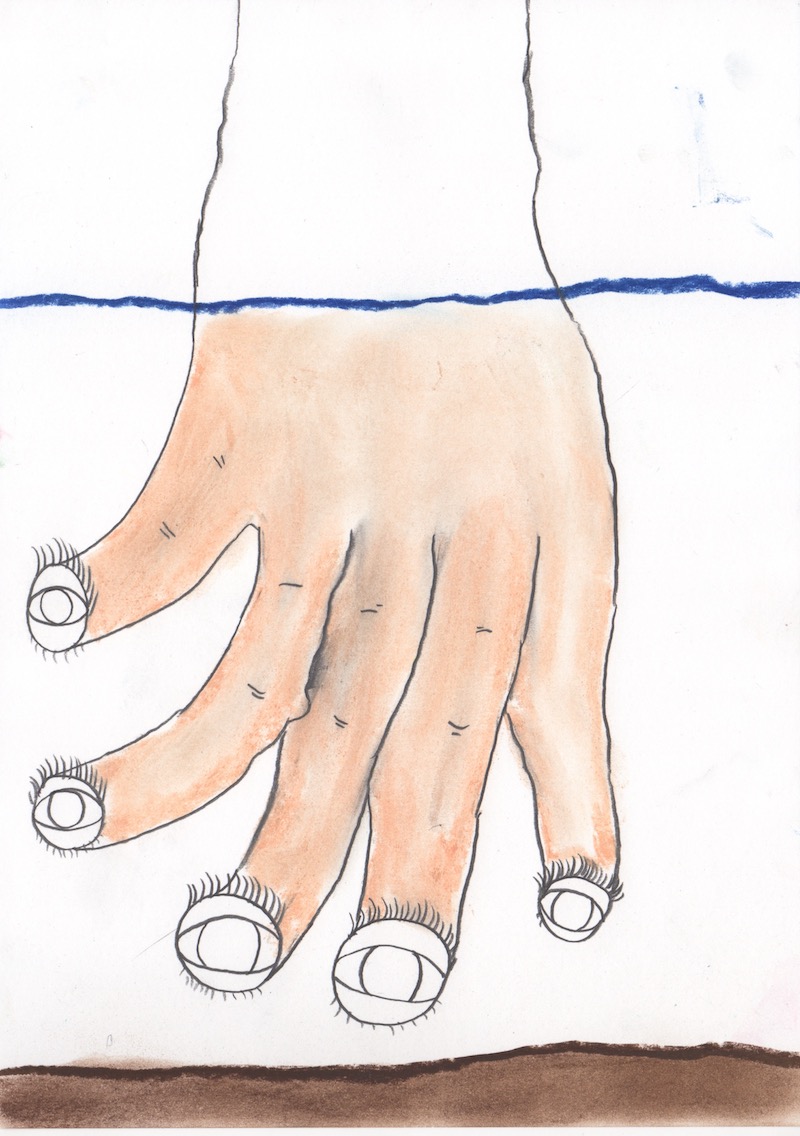

JULIETA ARANDA The knot…. The knot is not the rope, but my tongue is tied.

Case in point: because accumulation is not conscious—it just happens—here is a collection of useless things. Stubbornly holding on, insisting on their materiality, even though their use value has been exhausted.

As efficient as dull blades, overstaying the welcome that was tended to their existence. The telephone is broken, cannot be turned on anymore. So one wonders about the liminal existence of the words thumbed through it, and of the words that were thumbed back in response. Across the ether. All that is solid, is solid. And all that never was? What happens to the knots in a rope once the rope becomes invisible?

A rope is a toy. Write that down, make a note, make a knot, tie it around your finger. A rope is a weapon. Twisted technology—running 500 meters of cord along the sea—the implications of power inherent to the ability to draw a single horizontal straight line.

Knotting—weightless, mathematical, geometric, metaphysical, conceptual impossibilities; tied momentarily into this vanishing rope, frayed to its breaking point. How will I know when I make a mistake?

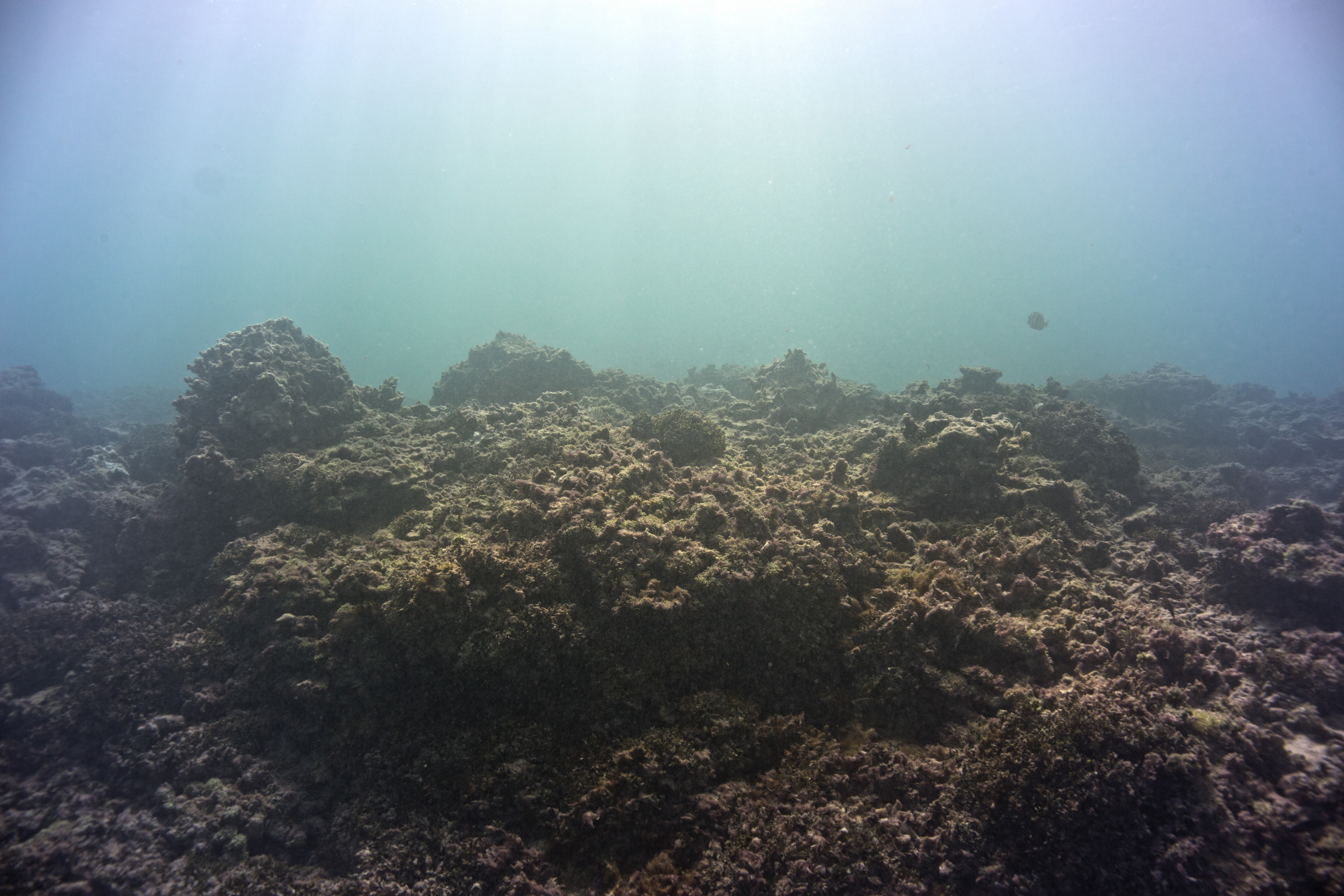

MARKUS REYMANN To start thinking from the Ocean is nearly impossible.

But drifting motionlessly in the surge above the kelp, synchronized movement according to an external plan, being able to breathe through a plastic lifeline in the form of a tube, I ask myself how long does it take to become seaweed.

Day 3: March 14, Wednesday Latitude: 36° 50.56’ S Longitude: 174° 45.5’ E Swell: harbor

Observations Every time an expedition starts, one needs to express a desire on behalf of all those that may not physically be part of it. This wish entangles those on the trip with those who remain: I want to put you in a place where a fish’s breath is audible in the middle of your day.

Our field of enquiry is constituted by the questions we are able to ask: What can we ask the Ocean?

It would be wrong to think that when one says “Ocean,” one is naming a “subject.” One could be as radical as stating that to say “Ocean” is, today, to say “art.” Art without the burden of institutional life, without the ideological twists of cultural politics, art as a practice that belongs and should belong to the artists, art facing the urgency of socializing with all those that care about life. Or, in other words, to say “Ocean” is to replace the historical notion of the avant-garde with a code that is not determined by form and the invention of new gestures but by an investigation of the substance of life, identifying this as the mission of art.

This would imply that all artists directly interested in life underwater, nature, new forms of sensing from a non-human centered perspective, and so on, are, of course, “in.” But it also means that all those not directly interested in thinking along those terms—who do not recognize the intelligence of art as lying in its radical interest in life—are even more important. Think about all the structures constituting the art world; about the impoverishment of a language inherited from past left and liberal social visions and the impossibility of reinventing these dreams under the same premises, under a late-capitalist economic system; think about the need of a new sensorium to invent new notions, to build new sentences, to embrace a new idea of equality and social justice. If we think so, we can see that saying Ocean is to say the expansion of the museum, of public space. That the Ocean is a source that reprograms our senses and entails a potential of transformation that may affect the future of architecture, communications, gender entanglement, economy, and art.

INGO NIERMANN PayPal of the oceans

In the morning, Ingo stumbles across a copy of Paypal’s founder Peter Thiel’s Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future (2014). The little book is meant to reaffirm our belief in smart outsiders’ outstanding contributions to the progress of humanity. We should not worry: the twenty-first century will still be shaped by these people. AI isn’t likely to take over before we will be dead anyhow. (There is no public knowledge of Thiel having any kids.) Still, the book has a strong nostalgic undertone: you (Peter Thiel) will never be as young and hungry as right before your first big success (PayPal).

There is a common narrative of unsuccessful outsiders turning into devils. Hitler rejected from an art academy! But there is as well the opposite narrative: people who once gained success by legitimate means but ran out of favor, energy, or ideas and turned into gruesome criminals or dictators. (There’s also a female version thereof: the queen who cannot deal with her sagging beauty and poisons Snow White.) Could Thiel’s turning into a devil still be reversed? Elon Musk, another co-founder of PayPal, is now 46 and still in good spirits about single-handedly transforming common modes of transportation.

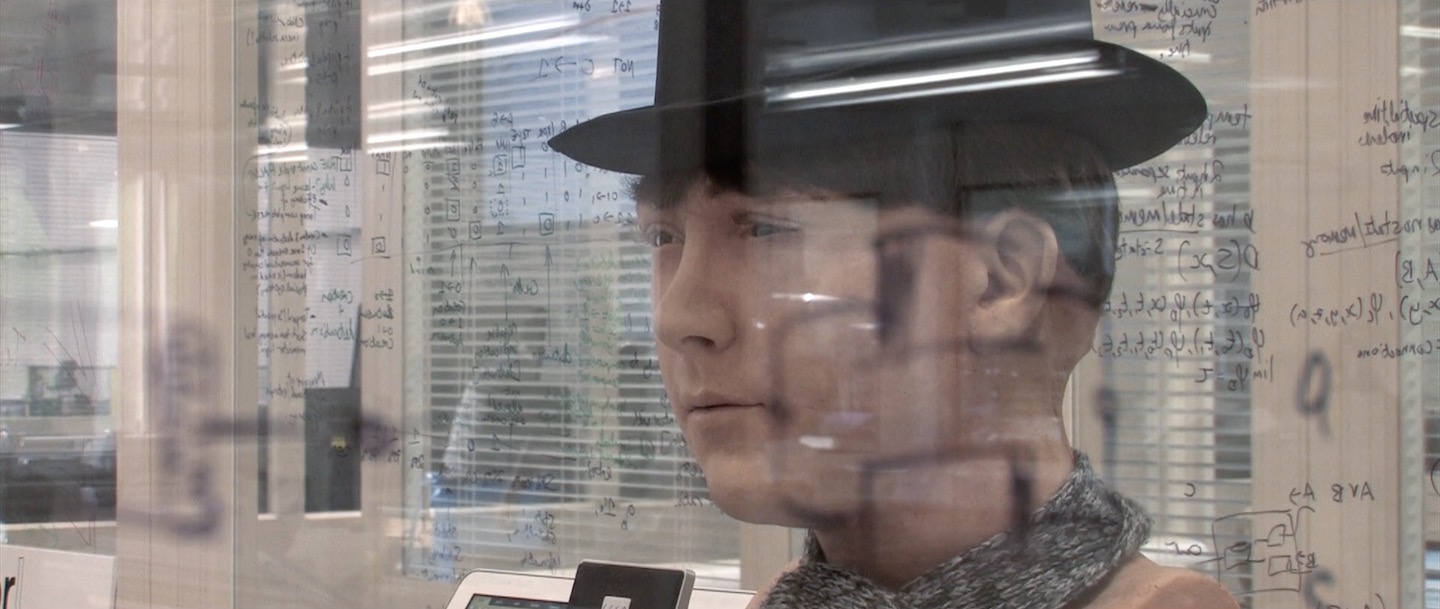

Ingo wonders: Could Albert and Roman film the members of the expedition in such a way that they would appear as a plausible (or at least likable) bunch of smart outsiders destined to build up the first multi-billion ocean startup? Ingo envisions a movie in between Don Quixote and The Expendables.

Day 4: March 15, Thursday Latitude 36° 17.39’ S Longitude 174° 48.7’ E Swell: harbor

Observations At first sight there are “things” that can only be described in positive terms, like the Oceans. It is beautiful how some experiences of nature—of the Ocean—remind us that to live means first and foremost to feel the world around us.

But sensibility is much more than just a faculty, it is an organ that senses ourselves and others, and our life is through and through a sensible life. Being at sea, I cannot but think of the many ways we need—we must—rehabilitate sensible existence from its marginalization at the hands of modern philosophy, art, and politics, and that the only way to do so is to create the conditions for philosophy, art, and politics by defining the ontological status of experience, of organic and inorganic intelligence. The Ocean is making me aware of its philosophical status. Being in the sea is being in an atmosphere, and being in an atmosphere is a very powerful image of thought, one that immediately calls for a challenge to the distribution of disciplines in the human sciences and humanities. I imagine a philosophy of the Oceans, a philosophy of plants, a philosophy of animals, as part of a philosophy of life that will, then, be entangled with all the developments in the philosophy of consciousness. I know that many think action is first, but how can we act differently if we are unable to deeply think/sense differently? Logically speaking, no real difference can emerge from a doing that only perpetuates or corrects and reforms the past doing. Also, how can doing be separated from modernity’s stubborn pretense to see the human spirit achieved only through material culture, the material production of objects and their exchange? So, doing cannot survive without an Ocean of conditions for biological existence. I see all this water and I feel a monstrous urge to reunite all the thinkers and artists, to meet here to start this new school of sensing intelligence.

INGO NIERMANN Suicide double bind

The expedition approaches Whakaari (White Island)—an active volcano that is supposed to attract sharks. Ingo imagines a neo-neorealist movie about a desperate person who is constantly moving back and forth between the shore and the crater of the volcano as they cannot decide if they would rather die in the volcano or in the mouth of a shark. The volcano seems like a safer bet but to end up as shark food would give the person’s life at least a bit of a meaning. (The person is not aware that sharks don’t like the taste of human meat.)

Day 7: March 17, Saturday Latitude: 37° 38-79’ S Longitude: 176 ° 08.95’ E Swell: harbor

Observations I missed a day looking at the Ocean. I gain a day looking at the Ocean. I think the distance between these two sentences should be measured in light years. Don’t get me wrong, I am not using the Ocean for my own needs, relaxing or meditating. Still, it is great to meditate with the Ocean. Before embarking on this trip, I only thought of immersion, but to my surprise I discover that we both, the Ocean and I, share a passion for rhythm. To some, this constant movement is a source of continuous unease, for me it feels like sleeping on the stomach of an Oceanic Barbapapa—the ship holds you, but the sea moves you in funny ways. I am sure there is an epistemology of rhythm, all these waves are there to express and communicate. Waves are the living world in terms of rhythmic patterns, rhythmic movement, and rhythmic representation. What if rhythm is the vital bond connecting art and the Ocean, science, and art, the Ocean and all the human and optic eyes observing it, all the bodies and devices sensing it? Strictly speaking waves and currents have no history, not in a material sense, but I am certain that the bodies of all the organisms living in the sea have a memory, just as we do. The history of navigation cannot be seen as the history of movement on the sea, but the history of swells, waves, currents, winds…

INGO NIERMANN Sulfurized

It’s the second day that we are exposed to Whakaari’s fumaroles. The volcano is much more active than when we visited it yesterday morning—the joint smoke column is now more than a hundred meters high. The most prominent ingredient of Whakaari’s smoke is sulfur. The fumaroles are surrounded by heaps of the yellow crystal. When we asked our guide if the sulfur wasn’t dangerous, he replied: “Why? All life needs sulfur.” He’s right, sulfur constitutes 0.25 percent of our body and sulfur baths are supposed to benefit our skin. Only that sulfur synthesizes easily with other elements. When we approached the fumaroles, our guide handed out bonbons. The additional saliva would help against a sore throat—an indicator of the pungent sulfur dioxide. Besides, there was a strong smell of rotten eggs (which reached us even on the boat), an indicator of the toxic hydrogen sulfide.

Some of us are suffering from headaches, mostly a bit faint. Due to the salt, the swimming, and the cradling of the boat, Ingo slept very well the previous days. He slept a couple of hours in the afternoon of the first day, then all night, then again for an hour at midmorning, and he feels greatly relaxed—actually pretty much as during and after visiting sulfurous hot springs. Is the relaxing effect of hot springs due to the inhalation of small doses of poisonous gas? A quick online enquiry reveals that hydrogen sulfide is about as dangerous as carbon dioxide. It prevents cellular respiration and makes you weak and dizzy—not exactly relaxed. Sulfur dioxide irritates the airways but also works as a vasodilator and bronchodilator. It opens the blood vessels and lungs—lowering the blood pressure and easing breathing.

Day 8: March 18, Sunday Latitude: 37° 38-79’ S Longitude: 176 ° 08.95’ E Swell: harbor

Observations The swell is strong and it is difficult even to stay seated, almost everyone is lying down. The swaying lasted only two hours, maybe three, but the fight against this movement is enough to leave a trace in all of us; we’re all tired of this intense wrestling with the Ocean. I try to write an entry in our diary, but the sea paralyzes any possibility of moving in a coordinated way. I start thinking about all the diaries in which, throughout history, explorers, scientists, and artists recorded their thoughts and observations while traveling across the sea. It would be amazing to read all the entries on the storms they experienced, on their bad days, on their sense of wonder. I would love to read, as well, all their entries on the millions of times they felt the sea, the boats, nature and its experience, awake in them an intense sense of bonding. I imagine infinite descriptions of bliss, leaving in the writer—and the reader—a strange joy of hope originating from a profound concern with the possibility of disappearance, indeterminacy, and traumatic exposure after the hard days at sea. And the sad vision of all the people seeking asylum in foreign lands and disappearing beneath the waves assaults me. I think about pain, the body in pain, and how we fail to go beyond seeing its image as an analytical and conceptual resource for thinking through the notion of subjectivity in light of current political priorities. Corporeality has been perpetually colonized. We also need a liberation movement, one that will allow for a more intimate relationship with all the bodies existing, one that will made these bodies explicit, that resists attempts to bring them under control whether by science, theory, fundamentalism, or neoliberal surveillance.

Day 9: March 19, Monday Latitude: 36° 11.90’ S Longitude: 175 ° 20.90’ E Swell: harbor

Observations Folding into being, unfolding into life. Redwoods. Mud. I quote from Alan Kemp, “Mudrocks are some of the most common yet least glamorous geological formations. They erode easily so they are often eclipsed by more robust and photogenic outcrops of granite, sandstone or limestone. Yet mudrocks are an important archive of the Earth’s history, and contain the detritus of the physical and biogeochemical cycles that shape and regulate global systems.”1

INGO NIERMANN Animated nature around Rotorua Natural steam vent cooker Hot pool tour Thermal land shuttle Mud spa Sulfur spa Twilight spa Geothermal bathing under the stars River sledging Travel in a WWII amphibious landing craft Agroventures Agrodome Hedge maze Zorbing (ball rolling adventure) Zipline Zipline canopy tour Scenic luge track Sky swing Mini diggers Guided bush walk & glow worms Treewalk

Day 10: March 20, Tuesday Latitude: 36° 11.90’ S Longitude: 175 ° 20.90’ E Swell: harbor

Observations Imagine being in a forest, an incredibly wild forest, and thinking about the jinnis—الجن—the demons, like the famous inhabitant of the lamp of Aladdin. Do you remember the Tales of A Thousand and One Nights? When Antoine Galland translated them into French from Arabic, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, they transformed the imagination of the time. On the night of May 8, 1709, Antoine Galland made a note in his diary about an extraordinary tale the Syrian merchant Hanna Diyab had just told him: “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp.” That was a dramatic night in Paris, marked by riots over food shortages. Diyab arrived in the French capital during this period and turned some of the dark nights into storytelling sessions that changed the course of A Thousand and One Nights. The tales he told were added to the translation and became part of world heritage through literature. The notion of zeitgeist appears a little later than the French translation of the Arabian Nights (1717). There is absolutely no evidence of any connection between the jinni of Hanna Diyab’s lamp and zeitgeist. Yet, I propose metamorphoses as a study of the importance of those images on the possibility of magically adopting another form without “losing,” about the importance of an inexhaustible will to interpenetrate the real.

INGO NIERMANN Driving through the rough sea feels like judo. It’s a constant up and down, back and forth, left and right. Sometimes, there’s an idea of a rhythm—only to be broken the very next moment by a surprise move. Some oceanic moves are subtle and trick us into counterbalancing them too much, others hit hard, as if the boat collided with a massive, solid thing. The sea’s ultimate win would be to make us fall flat or roll over. We can’t win over the sea, we can only sustain.

Day 11: March 21, Wednesday Latitude: 36° 11.90’ S Longitude: 175 ° 20.90’ E Swell: harbor

Observations Keeping a diary of a research trip is not equal to the research. I was relieved by reading the structure of Charles Darwin’s diaries, on the left page of the notebook his comments and observations, on the right, his comments on his personal matters and life. This parallel is impressively eloquent, it shows the need to observe and concentrate while traveling, but also how this task is part of the larger task of connecting and introducing this study in a larger project with public and personal implications. If Darwin would not record his efforts together with his personal worries, he would not be able to determine how much his life project, science, and work affect the type of person he is, the influence of his subject of study on his own mind. While traveling, my main task is to reach a state where you can absorb the most. Darwin was a master of this. It is a state closer to passivity than activity. The word research is tricky, it implies a goal, it requires delivery. But the Darwin’s diaries reveal an incredible sense of openness, of disposition, of attention. It is an attention living in a world of knowledge, but a knowledge elastic enough to allow for new discoveries to enter, to even challenge any previous interpretation of the world. I suppose this is why there were almost no explicit reflections made on the nature of species and the meaning of their geographical distributions in his diaries, but a record of plain observations. It is later, I guess, that this absorbed material transforms itself into analysis, into thinking and—why not—into a pedagogy. I used to think that systematized learning is the origin of all our political and social pain and yet one needs to remember that gymnastics were part of the Greek paideia (education). To study is a form of gymnastics and we should introduce, in profound but joyful ways, the study of the Ocean as gymnastics, as a series of exercises crucial to our education, from childhood to old age. This would yield insights into the larger philosophical questions concerning species.

INGO NIERMANN Rat Paradise

About 850 humans and an innumerable number of rats live on Great Barrier Island. Both share a lack of natural predators. Sharks could eat the humans but don’t like their meat. Even cats are too afraid of the rats and prefer other prey or processed food.

The human inhabitants enjoy a lush life on the island. There is plenty of fish and seafood, summers are lovely, winters are mild, and solvent tourists bring money. (Rachel Hunter has a house there.) But rats arguably have an even better life: They don’t have to build houses, pay taxes, buy or wear clothes, buy or cultivate food. The only disadvantage is that while they don’t really care about humans and indifferently accept their involuntarily kindness in taking them to undiscovered places or in offering them additional, particularly nutritious food through farming, livestock, and natural sanctuaries, almost all humans detest rats. Humans blame rats for eating their food and for spreading disease. Nowadays, humans even blame rats for the harm they do to third species: flightless invertebrates, lizards, birds, and plants.

On Great Barrier Island, at least ten species were supposedly eradicated by rats, which is enough moral munition to go for the eradication of the three types of rat that inhabit the island. The largest is called the Norwegian rat. In Europe it’s known as sewer or street rat but New Zealanders prefer to name it as an intruder, even though they intruded the country no less than 800 years ago (Maori) and 250 years ago (Europeans) and did much more harm to nature than the rats. The rats are so aware of the humans’ intention to kill them that they avoid them. Once a rat dies from poison, the other rats learn to avoid that poison. To continuously kill rats with the same poison you need a retardant function that makes the rat die weeks after digestion. As rats don’t have any predators, this method is pretty safe for other species. The baits are installed in ways that allow only rats to eat them. On Great Barrier Island, humans wrap trees with slippery plastic (to deter birds) and put the bait into a hollow stick small enough so that the mouths of other mammals cannot enter it. The bait is blended with the blood thinner brodifacoum, which makes the rat die gruesomely a couple of weeks after ingesting the poison.

When the expedition visits a bird sanctuary on the island, they hear hardly any birds but see lots of colorful plastic triangles with handwritten numbers along their way— signs that indicate the position of rat baits. The undated online article “Island Rat Eradications—History and Development” in Great Barrier Island Environmental News claims that rats have already been eradicated on more than 90 New Zealand islands. In particular, it mentions an inhabited and partly farmed island, only 0.5 percent the size of Great Barrier Island:

“Rakino is an example of an inhabited island close to a large city that has successfully eradicated rats. The island has 35 permanent residents, 75 dwellings, is partially farmed, and is 146 hectares in size. This island of mainly kikuyu pasture with coastal pohutukawas was cleared of rats using brodifacoum in bait stations set up in a 50 x 50m grid over the entire island. To ensure full cover there were 3 lines around the coastal cliffs, and offshore rock stacks were also baited. There were 750 bait stations and these were buried in the stock paddocks to reduce risk to cattle. They were refilled constantly for 3-4 weeks and then every three weeks until the bait was no longer taken. Overall this took about 6 months and used about a half ton of bait. On-going monitoring using tracking tunnels confirms the island has remained rat free despite the number of people coming and going from the island.”

Later on, the article claims that “every building, old mine shaft, cave, rock stack and small outlying island needs to be covered.” The expedition doesn’t see this currently in place on the island. In case such an encompassing measure has been active in the past, it hasn’t been a durable success.

Day 12: March 22, Thursday Latitude: 36° 07.16’ S Longitude: 175 ° 21.61’ E Swell: harbor

INGO NIERMANN Nature on probation

Ingo experiences New Zealand’s Northern Island as utterly non-exotic. Everything is like somewhere else, just in a new combination: the landscape is like Switzerland, only surrounded by the sea and a bit more tropical; the houses with their folded tin are like third-world shacks, just tidy and with windows; the rats are like anywhere else, but bigger because they lack natural enemies; the sharks are the same as around Australia, but they are not supposed to bite humans.

The resulting feeling is that of irreality: “No, I‘m not buying into it. It’s too good to be true. No surprise, this is where Hollywood shoots nature. All this might have been built just a few years ago.” Which is not that wrong. Even jungle-ish looking forests are barely a hundred years old, as almost no trees survived the systematic deforestation by the Europeans. The Maori culture also had to be reanimated after having been harshly marginalized, if not forbidden. The custom of burying the mother’s placenta under a tree to connect the newborn with nature was reintroduced in 1984. Te Reo, the language of the Maori, was officially accepted in 1987. Only 50,000 or less than 10 percent of Maori can speak it well. Most houses seem not to be more than ten or twenty years old.

New Zealanders experience the newness of nature and Maori culture as all too fragile. The import of plants and animals is rigorously limited. Predators like rats and feral cats that have been accidentally introduced by the Europeans and lack natural enemies are systemically eradicated. The nation’s largest tree, the Kauri, almost extinct around 1940, now has to be protected from a deadly fungus (Kauri dieback) that is spread by dirty hiker boots.

To avoid direct exposure for both sides, humans’ experience of nature is often animated like a theme park (see Day 7). It’s as if nature isn’t really present neither for us visitors nor for New Zealanders themselves. The experience is on probation.

Day 13: March 23, Friday Latitude: 36° 50.56 S Longitude: 174 ° 45.50’ E Swell: harbor

INGO NIERMANN Ocean Knowing

At the end of the expedition, Chus asks Ingo if it had made him experience the sea in a new way. He isn’t sure. A heavily rocking boat, the life on a boat, or a long swim into the open sea—nothing new. His ocean experiences on this trip have been again strictly superficial: he didn’t dive, he didn’t explore the deep sea, and he could always retreat to a cozy bed.

Ingo’s prevailing experience of the sea has been rather abstract: the constant knowing that it’s around. Even if all windows would have been darkened and the sea would have been completely quiet he would still know that it’s there. Like when you darken all the windows of your apartment and still know that you are not in the basement. It’s a knowing that you don’t even have to be aware of; it’s implicit like the knowing of your body. It’s the naturalization of nature.

Had this voyage been less comfortable, had we been more exposed to the elements, had the cyclone Hola hit the boat, Ingo’s memories of this trip would have been dominated by unique experiences. In not being trapped like on a cruise ship or an oil rig, but in living the life of a nomad with all the advantages of a steady home, the Dardanella expedition gave Ingo the feeling of aquatic normalcy. To experience this normalcy is still an immense luxury and might never become easily accessible. And if it would become easily accessible, it might disappear. (Even the sea would feel crowded if a billion people simultaneously spent time on it—especially the rims.)

The knowing of being enclosed by an entity far bigger and more complex than ourselves won’t disappear when Ingo leaves the boat and won’t stop ruling what he’s thinking and doing. In everything, Ingo will be a creature of the sea.

Alan Kemp, “Geology: Probing the Memory of Mud,” Nature, no. 406 (August 31, 2000): 951–3.