The barreleye fish has extremely light-sensitive eyes that can rotate within a transparent, fluid-filled shield on its head. The two spots above its mouth are similar to human nostrils. Monterey Bay, 742 m, 2004. Photograph: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

How might thinking approach a sea? From what beach or from what docks could it launch itself there? Should thinking plunge right in or should it float on the surface, handing itself over to the power of the waves?

I do not mean for these questions to be just metaphorical: thinking is not only intention but also extension, which means that it lives (drops and sinks or floats or hovers …) in the physical milieu of the elements. I do not mean for the opening questions to be metaphorical, then, even if the metaphor of the sea infiltrates one of the most serious texts of philosophy, Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. The secure site of reason, Kant claims, is like an island “enclosed in unalterable boundaries by nature itself.” “It is,” he continues “the land of truth (a charming name), surrounded by a broad and stormy ocean, the true seat of illusion” (CPR, B295/A236, p. 339). What is an island with “unalterable boundaries”? Having spent his whole life in the city of Königsberg on Baltic shores, was the Prussian philosopher unaware of high and low tides that change—ever so slightly but constantly, not progressively but in rhythmic advances and retreats—the jagged lines separating land and sea?

That said, Kant’s metaphor is useful. If the sea is supposed to be a figure for that which finite human reason can never hope to grasp, then it is not an object (above all, not an object of thought) with easily delimited outlines, which a subject may confront. While the unknown and the unknowable is (like) a sea, the sea is unknowable and unknown. Surely, marine scientists and oceanographers make out of the sea their object of study. But the uncertainties associated with global warming, rising sea levels, changing currents, drops in salinity, and all-pervasive plastic or heavy metals pollution destabilize not only the oceans but also the very tenets of science, rendering marine systems rather unpredictable. Although sophisticated computational models are proposed to deal with such radical unpredictability, a philosophical insight becomes unavoidable: like the climate, the sea is not an object; it exceeds the very parameters of a confrontation between subject and objects, to which science is habituated.

A curious situation starts to form right before our eyes: the unthought sea is constantly shading or shadowing (as well as ultimately overwhelming or underminding) the thought sea. This is not a matter of gradually dissipating the fog of the unknown and shedding the light of reason where it has not yet shined. (With regard to the metaphorical sea, Kant too says that the most that human voyagers surveying the dry land of secure knowledge can hope for is to map the boundaries separating this island of the knowable from the sea of the unknowable.) Rather, there are two paradigms involved, one of which is not recognized as such, exerting tremendous under-the-radar influence on the official paradigm. Let me sketch out, quite briefly, the relation between the two.

To put it very simply, the sea out there and the sea in our heads do not match. Often enough, they are even diametrically opposed. Far from a theoretical problem within the context of the correspondence theory of truth, in which truth statements result when an assertion corresponds to the actual object about which the assertion is made, this is a practical drawback. The sea in our heads is more than an abstract concept: it is wrapped in unconscious associations, hopes, and fears; caught in everyday mythologies of life and the surrounding world; shaped by strong undercurrents of emotional responses … The largely unconscious construal of the sea colors its conscious framing, determining our perceptions and decision-making capacities. Exacerbated by climate change, the complexity and unpredictability of marine systems that elude scientific models mirrors and widens the gap between the sea in our heads and the sea out there.

One example of the tendency I am describing is the phenomenon of pollution. In her wonderful book The Sea Can Wash Away All Evils: Modern Marine Pollution and the Ancient Cathartic Ocean, Kimberly Patton, professor of religion at Harvard Divinity School, puts her finger on the divide between the ancient ideas of purity, still operative in our unconscious representation of the sea, and the vast contamination of marine ecosystems.

The title of Patton’s book is a quote from a dramatic play by Euripides, Iphigenia in Tauris, dating back to 415 BCE: “The sea can wash away all the evils of humankind [thálassa klúsei pánta tánthrópon kaká].” According to this expression, the sea is understood as the force of purification: it washes away all that is bad and polluting in the physical and moral senses. The indistinction between these two (moral and physical) kinds of pollution is crucial, and it seems to be itself affected or infected by the uncertainties and blurriness of the sea.

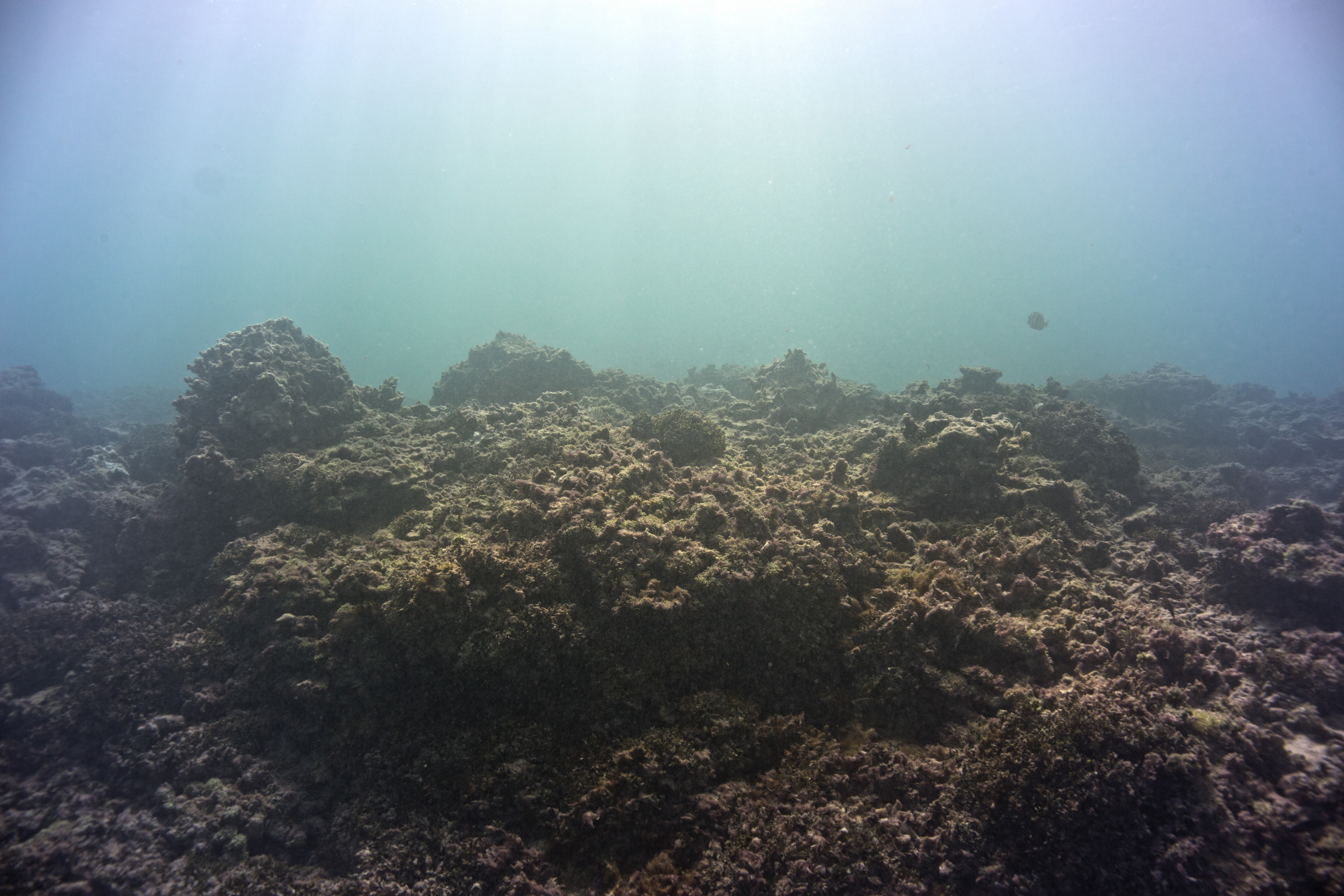

Nonetheless, in the twenty-first century nothing could be further from the truth. Global oceans and their inhabitants have been profoundly altered by the anthropogenic pollution (literally “the evils of humankind” posing life-threatening challenges to other-than-human beings) that has been released into them. So much so that in my 2020 book Dump Philosophy: A Phenomenology of Devastation, I argued that the massive dumping of pollutants into water warrants calling this classical element “hydrodump.” As I noted there: “The image of water that automatically forms in the mind of a person hearing the word rarely includes plastic debris, cadmium, mercury, lead, coliform bacteria, and petroleum hydrocarbons.”1

So, the marine wellspring of absolute purification is itself dangerously polluted, devastated, and reshaped by dumped pollution. And yet, our unconscious does not factor this into the worldview guiding our decisions and actions at every level of life, from the personal to the political. Measurements of water quality account at best for levels of bacterial contamination, not taking into consideration microplastic or any of the other pollutants I have mentioned. The same applies, mutatis mutandis, to the continued belief in the endless possibilities of marine regeneration or of nondepletable resources promised by the sea, despite the actuality of irreversible damage, mass extinction, the bleaching and disappearance of corals, overfishing, and so on. A rationally inclined mind insists that the mismatch between a faulty mental construction and realities on the ground (or, in this case, beneath the surface of the waves) may be easily fixed with correct information, ongoing monitoring, and sound scientific studies. What escapes conscious predictions, however, is an unconscious tendency to see only what we want to see, both acknowledging and repudiating (or negating) that which stares us right in the face. It is the tendency of disavowal, modifying the Biblical phrase “for they know not what they are doing” (Luke 23:34) to “for we know and don’t know what we are doing—and we keep doing it.”

Purity and purification are basic religious ideas and practices that have been by now, in most cases, disconnected from their sources. They are no longer related to organized religion and its institutions, such as churches, temples, or mosques. Despite their secularization, these ideas are still marked by their ritualistic origins. This is why they lend themselves to unconsciously guided, automatic mental associations and behaviors that, at the extreme, are obsessive and compulsive.

Belief in the unlimited possibilities of the sea fits together with insistence on its purity within a secularized, originally religious, framework. The regenerative potential of the sea beckons with redemption; the inexhaustible resources it is supposed to hold have a whiff of grace about them. And then there is something else at play.

Compared to the relative stability of land (which is, for all that, prone to earthquakes and landslides: think back to Kant here), the sea is indeterminate—a quality that nourishes the illusion of sheer possibility. At every moment, the sea is more elementally possible than it is actual. Whatever its current state, it will very soon be different: besides the changing tides, fluctuating weather patterns will bring with them either calm or a storm, and the waves will now crush on the shore with tons of detritus, or bring with them bioluminescent algae, as on some beaches of Southern China, Australia, and California. The evidently and quickly shifting state of the sea thus tells us that it is more of the future than of the present.

Still, a possibility is always a double-edged sword, holding in store promises as much as threats. We do not know what the sea will bring. (“I know not what tomorrow will bring” was the very last phrase written by Portuguese poet-thinker Fernando Pessoa on his deathbed.) Why does the positive side of possibility invariably gain the upper hand in our unconscious relation to the sea? Why not fret about the kind of outcome in which the sea washes away all good alongside all evil, doing so with the utmost indifference to the distinction between them?

My suspicion is that the lopsided, usually implicit (unarticulated, unconscious) hopes about the unlimited possibilities of the sea flash before us a mere façade of the future, while holding onto a sense of an everlasting present. In keeping with this structure, change is inessential, epiphenomenal, nothing more than a constant fluctuation between fixed poles. For this reason, marine possibility is unlimited: it entails an endless repetition of the same. Opposites converge. A quasi-religious vision is in accord with a mechanistic worldview, in which the future is yet another present, virtually indistinguishable from a past present—and so on, ad infinitum. The ancient and modern sunny optimism with regard to the sea is, perhaps, attributable to this paradox.

We are lulled into false comfort by what we take to be mechanical repetition: the regularity of high and low tides, seasonal changes that bring with them the annual “death” and rebirth of plants … And we think that life in general follows similar regular rhythms of regeneration by means of generational self-replacement (“the Phoenix complex”). In other words, we know all too well what tomorrow will bring. Rising sea levels, global heating that wreaks havoc on the parade of the seasons, and mass extinction are experienced as a rude awakening by those who are not victim to the dynamics of disavowal, that is, those who do not unconsciously acknowledge and deny the radical nature of these events. But, returning to the sea, it is fair to say that, though the two are often interrelated, the spatial ingression is always more worrisome than the temporal one: land that becomes permanently covered by the sea beyond the daily or seasonal variations in the tides, and saltwater intrusion beyond occasional storm surges, are just two examples of spatial indeterminacy driven by the sea, the indeterminacy which overwhelms (indeed, overflows) the rhythmic changes that unfold in time.

Everything I have said about thinking the sea thus far is applicable to the task and the work of thinking. It is sorely insufficient to think the sea without thinking at sea and, thereby, revising Kant’s rigid distinction. We can no longer afford either to ignore the sea (metaphorical and literal) because it is not an appropriate object of thought or to attempt mastering and dominating it as any other object. Likewise, we can neither ignore the unconscious because it does not conform to the rules of conscious representation, nor can we master it, by translating it into the terms and categories of conscious psychic life. So, what is to be done? Or, to repeat the opening question of this essay: How might thinking approach a sea?

I hope that at least one thing has become clear: in order to respond to the challenges posed by climate change in coastal areas, as well as by the ongoing transformation of marine expanses into energy, dietary, and other resources, it is necessary to develop an analysis of the unconscious construction of the sea. Since unconscious projections surreptitiously determine conscious reasoning, decision-making, and planning, such an analysis is a precondition for an effective formulation of policy ideas and goals.

At the same time, the unconscious itself might be analogous to a sea, from which small bits of dry land, of conscious existence, jut out, more or less exposed by the low and high tides of psychic life. Not only Kant but also Freud had this premonition. In the opening pages of Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud discusses the “oceanic feeling,” a term which Romain Rolland coined in his 1927 letter to Freud. “It is a feeling,” Freud relates, “which he would like to call a sensation of ‘eternity,’ a feeling as of something limitless, unbounded—as it were, ‘oceanic’” (SE 21: 64). Freud confesses that he “cannot discover this ‘oceanic’ feeling” in himself and further specifies it as “a feeling of an indissoluble bond, of being one with the external world as a whole” (SE 21: 65). Simply put, the oceanic feeling is that of non- or pre-individuation, subtending and washing up from every side on the shores of individuation. Ultimately—but also in the first instance—the unconscious is the ocean of the oceanic feeling; hence, our unconscious projections about the sea are also our unconscious projections about the unconscious itself.

Given the growing, spatiotemporal, elemental indeterminacy of coastal areas, the analysis of unconscious constructions of the sea should proceed hand-in-hand with the cultivation of two sorts of vision: overviewing the sea from the standpoint of dry land, and surveying dry land from the perspective of the sea. Tidal zones and marshes are on the move, rendering this double perspective nonnegotiable. Our analysis of unconscious presuppositions, in which the mental image of the sea is wrapped, is tantamount to the marine vision of terra firma, whereas conscious decisions on all matters of the sea are the land-based gaze scanning the horizons of the sea. I am convinced that only in the constantly traversed gap between these perspectives can one find a sensible, ever evolving response to the contemporary challenges.

Michael Marder, Dump Philosophy: A Phenomenology of Devastation (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), xi.