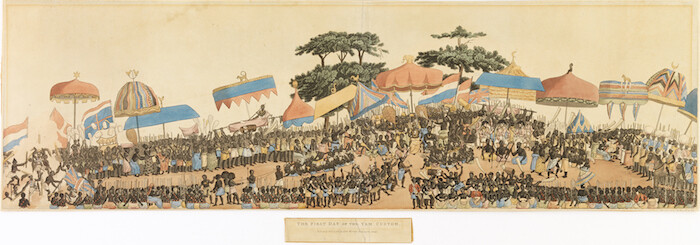

Copying and re-using others’ images or artworks always generates considerable debate. Just like solving a crime, it becomes necessary to establish a motive. Almost 200 years separate Thomas Bowdich’s original colored aquatint The First Day of the Yam Custom (1818) from Godfried Donkor’s large replica, which takes the same name and hangs center-stage in his first solo show in Ghana since 2006. His purpose is not repetition or appropriation, but re-imagination and re-presentation.

This nine-panel painting, along with three other pieces also on wood and a series of ten collages, is the product of Donkor’s recent four-month residency with Gallery 1957, Accra. Supported to set up a studio, and given time to reconnect with his country of birth and childhood, the artist has re-produced and re-conceived a number of Bowdich’s images, occasionally introducing details from his own observations. The works are hung around a newly created gallery space, in the midst of which sits A Gold Stool (2017) placed upon a plinth covered with a dark cloth.

The First Day of the Yam Custom (2017)—almost eleven meters wide—repeats the layout and composition of the earlier and smaller image, a mere 725 mm across. Using oil and acrylic rather than resin and ink, occasionally accompanied by an application of gold leaf, the artist recreates the procession of the Asante Yam festival in Kumasi, as witnessed by Bowdich in 1817. The Englishman, employed by the Royal African Company, was part of a delegation negotiating a trade treaty with the King of Asante. In 1818, he returned to Britain and published his account in A Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee, &c. (1819). His illustrations are some of the first images recorded by a European of the Gold Coast, now known as Ghana. Today the aquatint is held in the National Maritime Museum, London.

Donkor first saw Bowdich’s image of the yam festival in 1995, when he was studying African Art History at SOAS University of London. Later the same year he observed the annual durbar in Kumasi, where hundreds of people continue to pay respect to their king and celebrate the beginning of the yam harvest. Comparing his photographs to Bowdich’s print, he was amazed at the similarities of the event across two centuries—the colorful umbrellas topped with animal motifs, the king’s throne, and the figures wrapped in Kente cloth. Yet Donkor’s epic piece is subtly different—his colors are darker, his figures flat, he never uses shading. At either end he has extended the crowd scene to envelop the modern-day viewer.

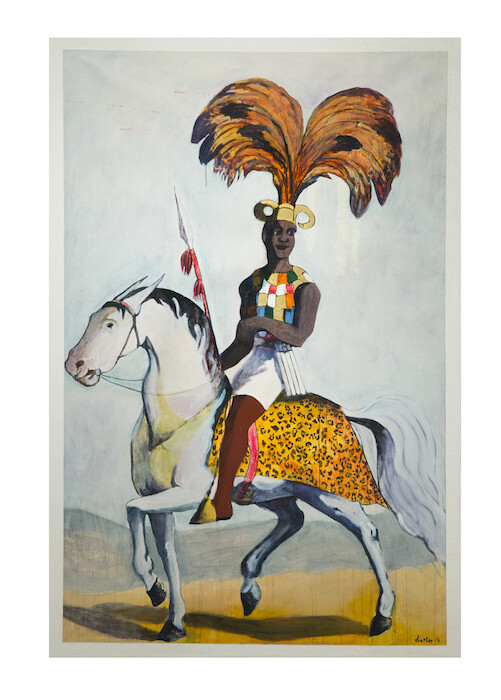

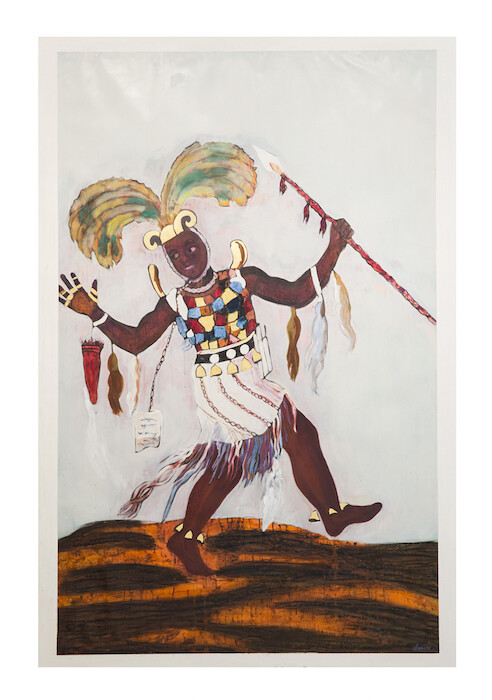

His Ashanti War Captain I-III (2017) are also based in part on Bowdich’s images and account. Realized in oil, acrylic, ink, and gold leaf and life-size, they evidence the military prowess of the Asante then as much as the pageantry of the king’s court now. The collages are made of paper used to print The Financial Times and cut-outs from the artist’s 1995 photographs. Together with the inclusion of Asante, Jamaican, and Barbadian proverbs as well as financial data, they become a form of story-telling, offering glimpses of Asante history and mythology. In the midst of all these works a small stool sits on a plinth. Replicating the domestic stool found in every Ghanaian’s kitchen, A Gold Stool serves as a symbol of popular culture and in its familiarity, it offers a stark contrast with the re-presented images.

Donkor’s retelling of Bowdich’s account is focused on questions of history, authorship, circulation, and authority. By presenting these works first in a Ghanaian gallery, he offers a reminder that nineteenth-century images of Africa were circulated widely outside the continent but seldom within it. The trade treaty that Bowdich was involved with may have secured peace for British settlements along the coast, but it also heralded the start of the rush to seize Asante gold for Europe: the festival procession contains flags from Holland and Denmark as well as Britain.

Donkor has consistently been interested in the representation and histories of Africa and its diaspora, as attested by both his Slave to Champ (2007) and Black Madonna (2004) collages. Here he considers shared histories and how cultural identities are constructed. His works highlight an inherent contradiction in the way that the reproduction of images has been used to create and reinforce identities of people and place. The fixity of identity, the work suggests, is imaginary. In re-presenting Bowdich’s version, he slyly acknowledges that much has changed in Ghanaian society, even though the Asante have found ways of retaining their culture and traditions despite centuries of European exploitation.

This exhibition re-examines history and the single-perspective stories of which it is often comprised. The exhibition is curated by Koyo Kouoh, and while the show’s straightforward layout without supporting information seems to preclude the visitor’s deeper engagement, the project’s long gestation and complex associations confirms the importance of peer discussion between artist and curator. In reviving Bowdich’s images Donkor has not only changed their authorship but also re-directed their meaning and purpose. In re-circulating them, he is contributing to an important re-evaluation of power relations and representation.