October 18, 2023–February 25, 2024

If the Global South is itself an imagined community then, this edition of Videobrasil suggests, therein might lie its emancipatory power. Exhibitions focused on the Global South are in welcome vogue, from the current Bienal de São Paulo to next year’s Venice Biennale, but Videobrasil has been ploughing the furrow for thirty of its forty years now. While curators Raphael Fonseca and Renée Akitelek Mboya took a line by poet Waly Salomão as their guide to select sixty artists from thirty-eight countries out of 2,300 open submissions, this edition is most effective as a snapshot of the conscious and unconscious preoccupations of a constructed region. One that, for the curators, stretches from South and Central America, to Africa, Asia, and former Soviet states (as well as Indigenous artists from any continent). This region, the curators suggest, is “a plural and fertile accumulation of visions.”1

What binds this imagined community together? On a series of plinths, Ali Cherri has placed what seem like stone monuments of antiquity—which they are, in part. The scrunched, snarling face and neat mane of Lion (2022) is a historic architectural fragment that the Lebanese artist found in a Beirut antique shop. The bulky clay body, however, is the product of Cherri’s own hands; likewise the doe-eyed head of Standing Figure (2022), which possesses a similarly amorphous body, like Frankenstein’s creature. In common with much of the work exhibited, these sculptures’ sense of self is constructed piecemeal, through the accumulated ruins of history.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Youqine Lefèvre’s moving video installation the Land of Promises (2023). Against a photograph of a crumbling building in rural China printed in vinyl onto the wall, near other framed photographs from Lefèvre’s travels through Hunan Province, a video plays on a monitor. In thick Belgian French, the artist narrates amateur footage documenting a trip made by a group of Belgian couples in early middle age across China in the mid-nineties, eventually arriving by minibus at an orphanage housing babies born in violation of the CCP’s one-child policy (in place from 1979 to 2015). The footage—it has the pasty graininess of the mass-market camcorder and shaky handling of an amateur cineaste—shows a baby being presented to its adoptive parents. Lefèvre nonchalantly reveals that she is the baby shown in the video: this is the first time she met her father, who filmed the occasion. The jump-cuts in the footage when her father stops filming only to resume, minutes or hours later, imply absent memories in which a fuller sense of identity is irretrievably lost. “Time has erased this information,” Lefèvre says.

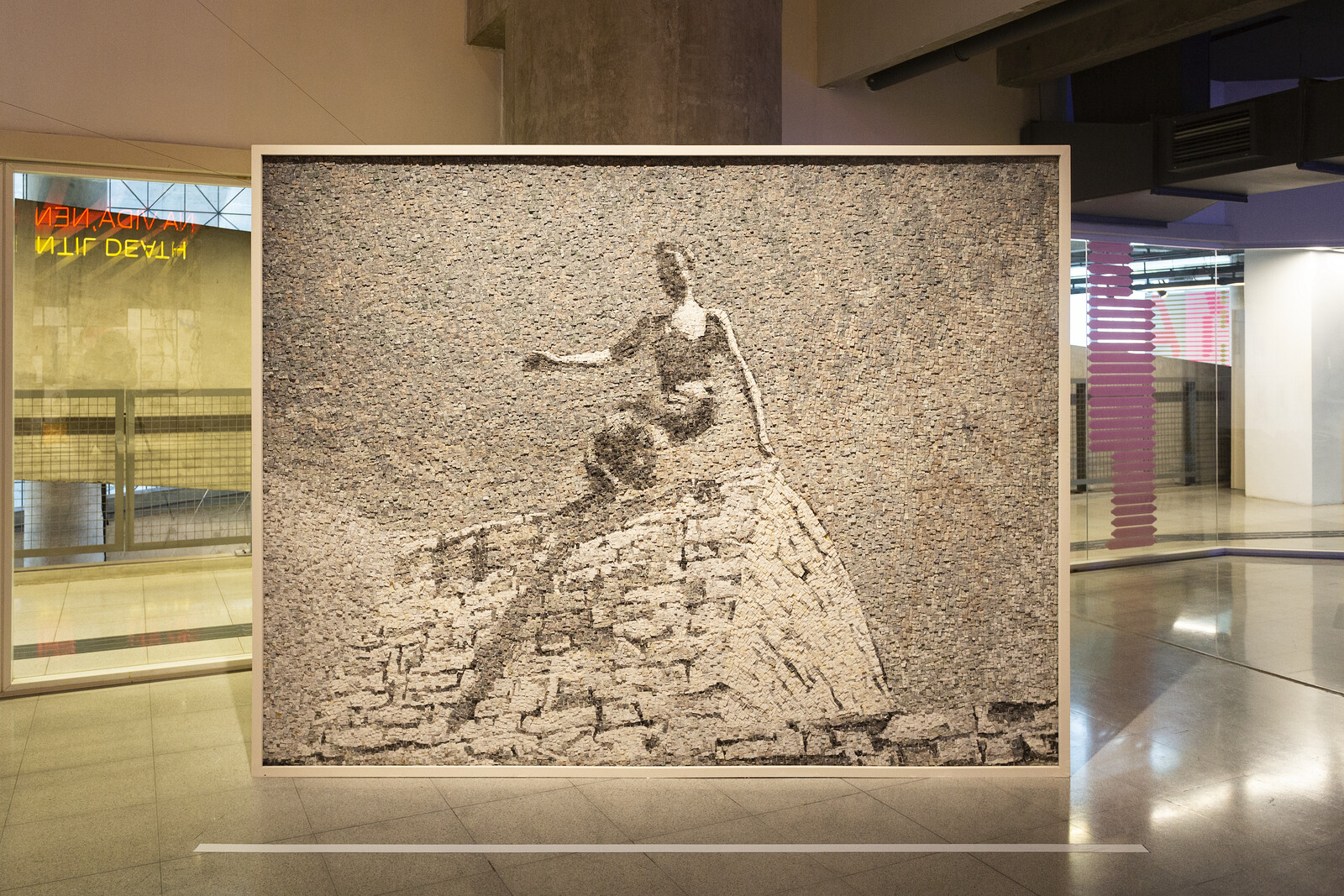

The fallacy of intransigent selfhood, fixed by a single nationality, is also suggested in Adrian Paci’s Il Salto (2014). This image of a soldier jumping over a wall, a still from an army training video, is reconstructed in a two-meter–tall mosaic of differently toned grey marble blocks. It feels as if the monument of militarism and the nation state might crumble with the slightest push. Isaac Chong Wai’s series of six prints, Crying People (2022), similarly undermines belligerent nationalism. Each is partially shrouded behind an individual metal chain curtain, in which the artist replicates found images of people in China and North Korea mass-crying at state funerals, but with their tears enlarged and darkened.

Doplgenger’s Fragments untitled (2021–22), a four-channel video work for which the Serbian duo have edited and collaged television footage broadcast around the dissolution of Yugoslavia, feels equally haunted. One of the floor monitors shows a compilation of perturbed looks, opening and closing doors, phones ringing, and sharp breaths from soap operas and dramas of the era; in the most recent of the series, we see footage of the infamous Dinamo Zagreb–Red Star Belgrade riot, which took place between Croat and Serb fans at Maksimir Stadium in May 1990, digitally manipulated—in a style reminiscent of Paul Pfeiffer—so that only the riot police remain. They maneuver around the silent pitch, ill-equipped and lost, their foe absent.

If the Global South is marked by colonial erasure and violence, it also provides opportunities for emancipatory self-construction—a place where, in Fonseca and Mboya’s vision, a more ecological, intersectional society might emerge. Maksaens Denis’s My Dreams (2021) is a twenty-minute video documenting hundreds of young men ransacking the streets of Port-au-Prince. While My Dreams suggests that the ongoing security crisis in Haiti since the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse is fueled by machismo and desperation, Denis also intercuts the footage with tender scenes of two naked, embracing men—an imaginary queer alternative to the current hell. Maisha Maene’s fourteen-minute Mulika (2022) presents another dystopia, when an “afronaut” (as Maene terms him in his artist statement) lands in Congo and wanders a landscape scarred by environmental crime and capitalist exploitation. Yet this figure—in a shiny, slightly glamorous space suit—acts as a beacon of hope amidst the reality.

At the fifth World Social Forum in Brazil, in 2005, the Portuguese writer Jose Saramago argued: “I consider the concept of utopia worse than useless […] What has transformed the world is not utopia, but need.”2 This transformation is needed in the relationships between species as much as between humans, and the tension between ecological disharmony and coexistence is at the center of films by Georgian artist Andro Eradze and Brazilian Maurício Chades. In the former, Raised in the Dust (2022), the camera is trained on a dark wood as fireworks illuminate the trees and provide a series of loud, popping bangs. This disharmonious human soundtrack is cut with occasional glimpses of taxidermied animal faces.

Chades’s Cemitério Verde [Green Cemetery] (2023), which follows the artist’s construction of a garden near Alto Paraíso de Goiás, a city in central Brazil, could be described as an avant-garde nature documentary, though its abstract soundtrack and blurry takes lend it the weird and dreamy feel of Eradze’s work. With the camera lighting on insects and blooming flowers, the garden feels like a paradise shielded from the pesticides and clearing fires of the land beyond, given over to agribusiness. “The only time and place where our work can have impact—where we can see it and evaluate it—is tomorrow,” Saramago continued in that speech. “Let’s not wait for utopia.” Whether Chades’s garden, like the Global South as imagined in this biennial, is an impotent utopia or a blueprint for tomorrow, is left up to the viewer.

De Voltao Ao Futuro,” 22nd Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, https://bienalsescvideobrasil.org.br/direcao-artistica/.

See Jose Ramos, “Toward a Politics of Possibility: Charting Shifts in Utopian Imagination through the World Social Forum Process,” available online: https://jfsdigital.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/112-A01.pdf.