The dedication of the guidebook accompanying “Long March Project: Building Code Violations III – Special Economic Zone” reads: “To the freezone imagineers.” A portmanteau combining “imagination” and “engineering,” “imagineering” was first coined by the Alcoa Corporation during World War II, and later popularized—and trademarked—by the Walt Disney Company during the 1970s to extol the modus operandi of their construction of Disney theme parks worldwide. The imagineers, their parks, and the visitors hooked on the promise of speed and disequilibrium: this sci-fi-infused image makes an apt analogy for the Special Economic Zones that have mushroomed in China since the Reform and Opening Up process. It also offers a point of departure for this timely survey on artistic investigations into the great acceleration of China’s technological epoch.

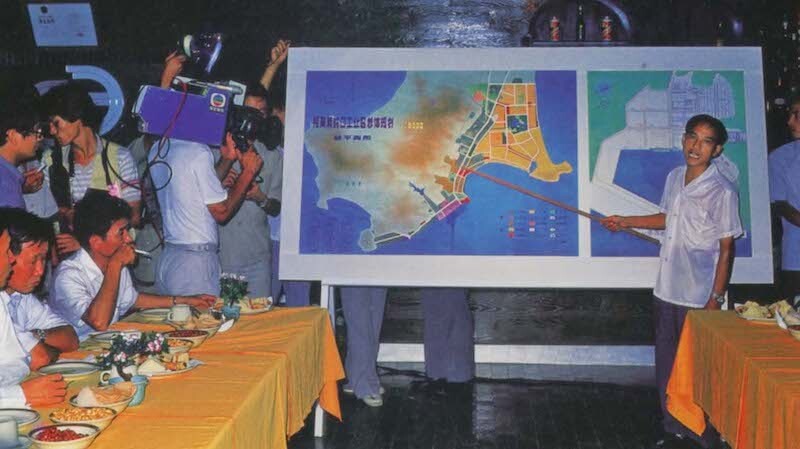

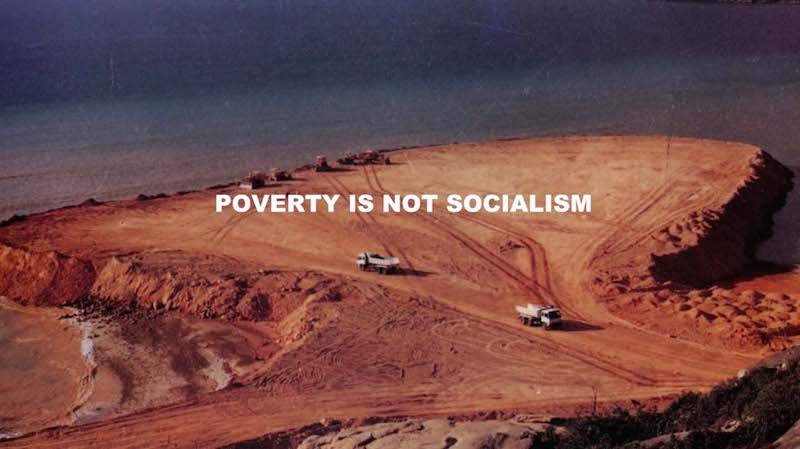

Four decades after the Reform, the zeitgeist of China today can best be summarized as “an unfettered optimism for the future and the rapid development of China’s technological infrastructure,” as curator Zian Chen and artist Liu Chuang write in “Revisionist Accelerationism,” their essay for the exhibition’s catalogue.1 Arguably, the seeds of this futurist disposition were first sewn by Deng Xiaoping’s cabinet in Shenzhen, China’s first Special Economic Zone, the original site of the country’s tech hub boom, which is the focus of Liu’s work in the exhibition, also called Special Economic Zone (2018). Liu moved to Shenzhen after college, in the early 2000s; his experience there, which included dabbling in advertisement and a failed entrepreneurial attempt to run a counterfeit painting production company, will be relatable to many of his generation, and informed much of his socially engaged work, a lot of which depicts the lived realities of populations in Chinese urban centers. In the video Special Economic Zone, Liu interweaves found photographs, archival sound recordings, and personal history into a biopic of a city that transformed from a desolate fishing village into a metropolis of more than 10 million inhabitants within three decades. At one point, there is a montage of familiar slogans, from “Time is Money” to “Science and Technology are Primary Productive Forces,” fading in and out superimposed over images of the city under construction. The focus then shifts to a propaganda exhibition in Shenzhen dedicated to the city’s miraculous rebirth; in that exhibition there is a digital map of the Special Economic Zones in China, dozens of red dots twinkling along the coastline, on the verge of encircling the country. The video captures the extent of the state’s orchestration behind what, for the public, is a shift in technological, temporal, and ontological awareness. And, as if tailor-made for this show, it highlights the inversion of “normalcy” and “state of exception” in contemporary China, which is the crux of the polemic of this exhibition series. (First launched in 2006 by Long March Project, the research group founded by the Beijing commercial gallery, “Building Code Violations,” has put on four shows, the third of which was mounted at Long March Space in Beijing over the summer before travelling to the Times Museum.)

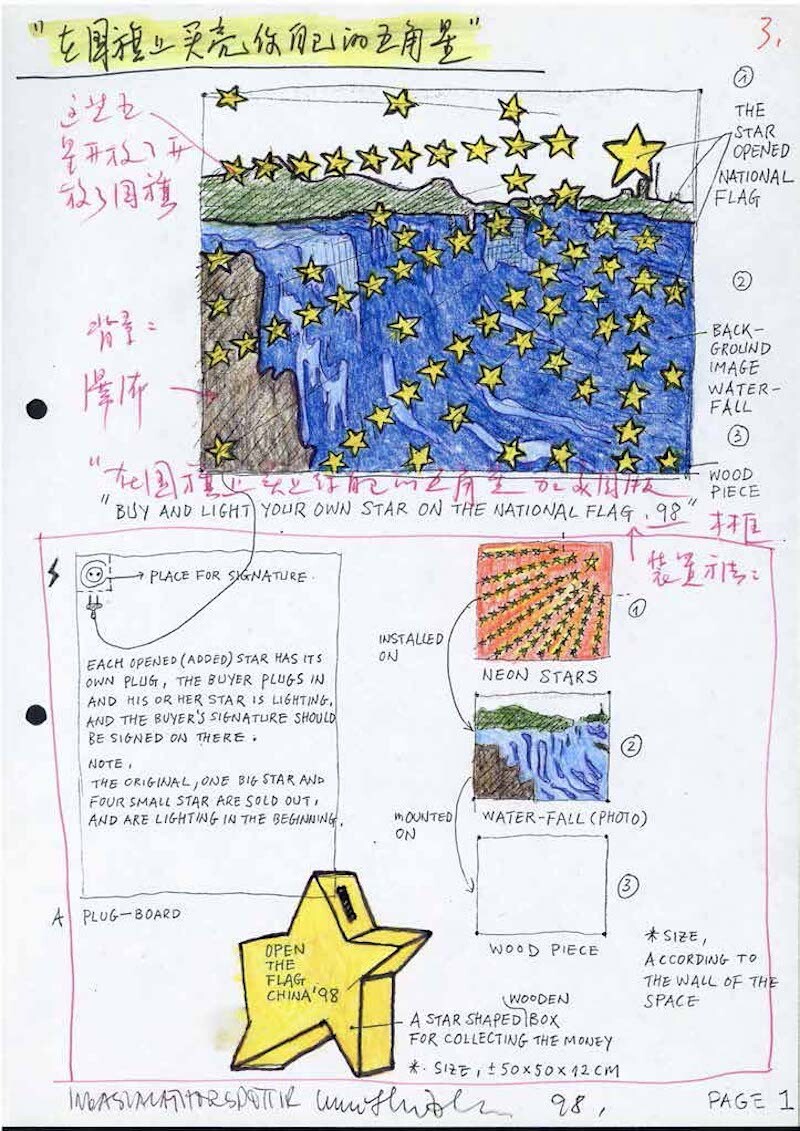

The second half of Liu’s single-channel video comprises documentation of an early iteration of his ongoing project, Buying Everything on You (2005–ongoing). For this work, Liu approached migrants who were job-hunting in a labor market in Shenzhen and asked if he could buy their belongings. He then exhibited those objects in the museum as stand-ins for the people he had met. A witty testimony to the distribution and implementation of capitalist ideology in the public imaginary of post-socialist China, the work is shown alongside Inga Svala Thórsdóttir & Wu Shanzhuan’s conceptual installation, A Letter to the Nation’s Manufacturers (1994) and Showing China from its Best Sides ’95 (1998), which relates to Liu’s work in taking a process-driven approach to probe the vanishing boundaries between art, commodities, and artifacts in global capitalism. The installation includes paper documents of the duo’s proposal for a show in Barcelona in the 1990s, such as the artists’ letter addressed to a manufacturer, as well as the contact information of various manufacturing companies that the artists meant to exhibit as artworks.

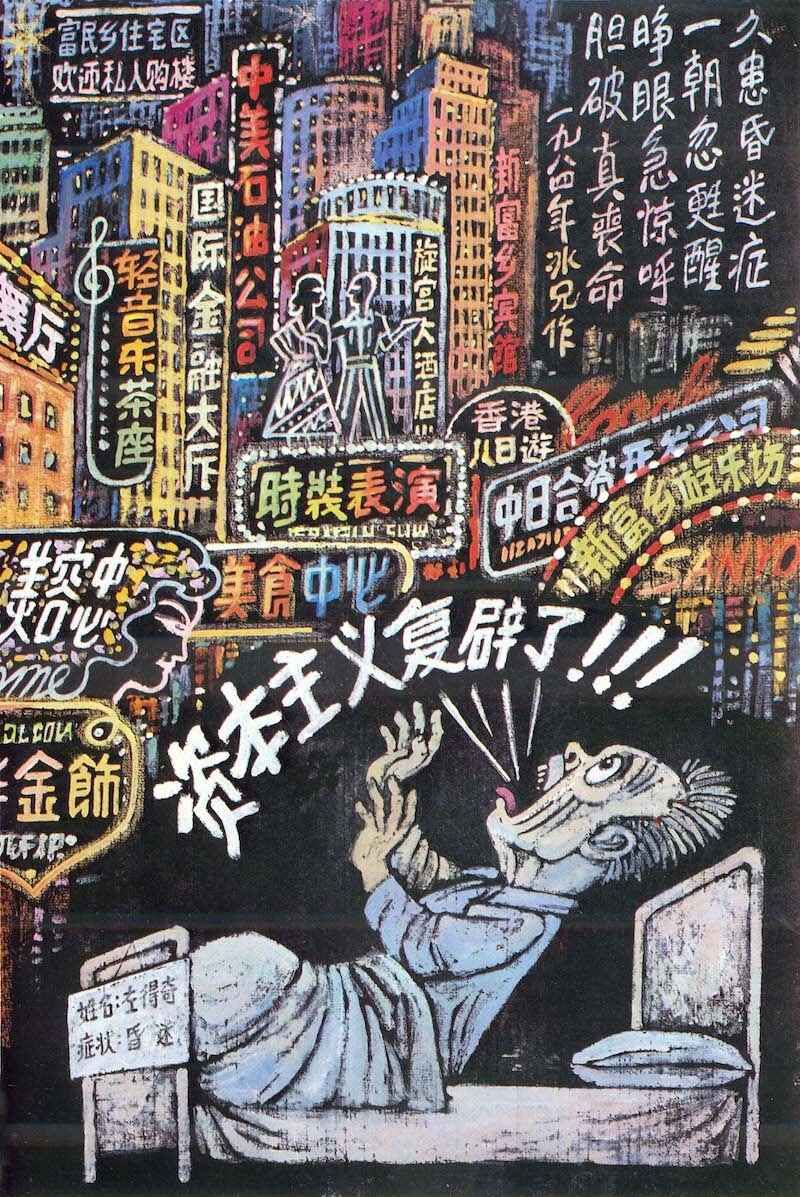

The aforementioned works were included in the first iteration of the exhibition in Beijing over the summer, but the Guangzhou edition features a new selection of works and archives. Some of these pieces, such as the late Liao Bingxiong’s political cartoons from the 1980s and ’90s, were pulled from the collection of local institutions. Where No One Has Been Before (1954), a controversial woodblock print by Liang Yongtai made in the heydays of socialist realism, is a fictional scene that alludes to the rising conflicts between China’s infrastructure building project and nature. Breathe (2017), an example of Liang Shaoji’s lifelong work with silkworms, displays the kind of organicist ruminations that run through ancient Chinese thought. Comprising a series of Buddhist sculptures that the artist scavenged from a group of apprentices and hung on a window railing, they simultaneously resemble homemade cured meats and cyborg extensions. Xu Qu’s Balcony (2017) calls to question the inscription of value by different modes of production, like technology and artmaking. Compared to the Beijing iteration of this exhibition, which focused on capital and technological advent, these new additions weave together a more pronounced narrative about the history—and philosophy—of technology in modern Chinese thought.

Focusing on historicizing technological acceleration in contemporary China, most works in the show share a conceptual density, almost at the risk of seeming detached from lived realities. Hao Jingban’s video essay Slow Motion (2018) goes against this tendency. It juxtaposes footage of Beijing’s draconian suburban slum clearances at the end of 2017 and YouTube clips of objects destroyed by physical forces, accompanied by the artist’s evocative association between the technique and ethics of filmmaking and Max Roach’s buoyant jazz. It’s exceptional how Hao employs the temporal nature of moving images in opening up an interstitial space to speculate on the politics of speed while magnifying the pain and violence that are often neglected—or deliberately shunned—in narratives of progress. As the film ends, the melody of Roach’s song “Freedom Day” (1960) lingers, and gives me chills: from mobility to liquidity, what the freezones, in their polyvalent forms, essentially exploit is the promise of freedom. What kind of artistic engagement would be the most effective in deterring—or intervening with—that cruel optimism?

Zian Chen and Liu Chuang, “Revisionist Accelerationism,” in Long March Project: Building Code Violations III – Special Economic Zone Guidebook, ed. Zian Chen (Beijing: September 2018), 88.