The photographs in the first UK show of the Essen-based artist Niklas Taleb describe intervals and cadences rather than people or events. In particular, they outline the rhythms of the home: most of them show the artist’s apartment, where, it would seem, time passes slowly. Arranged in a spare hang across the gallery’s two small-ish spaces, these are reserved images in which rooms feature more prominently than the family inhabiting them. Often untitled yet all dated 2023, they are populated by toys and crockery, computer screens, flowers, and mementos. The remains of a snack sit on a carpet, multicolored building blocks are balanced on the rim of a drawer, snapshots of relatives are tucked in the gilt frame of an old print. In their reticence, these glimpses into the day-to-day life of a household leave viewers to establish what narrative and thematic continuities they can.

The family itself is largely offstage. The shadow above the building blocks may be the artist in silhouette. Elsewhere, a woman, his partner perhaps, files an infant’s fingernails, but only their hands are visible. Social life makes a marginal appearance in two pictures of visitors absorbed in their own thoughts. In the liveliest scene here, four friends sit close together in a café or bar. As if to muffle their animation, Taleb divides the picture into two horizontal strips and swaps them around while focusing his lens on the textured wall behind the group rather than on the figures themselves. An image of a social occasion, it is also a still life.

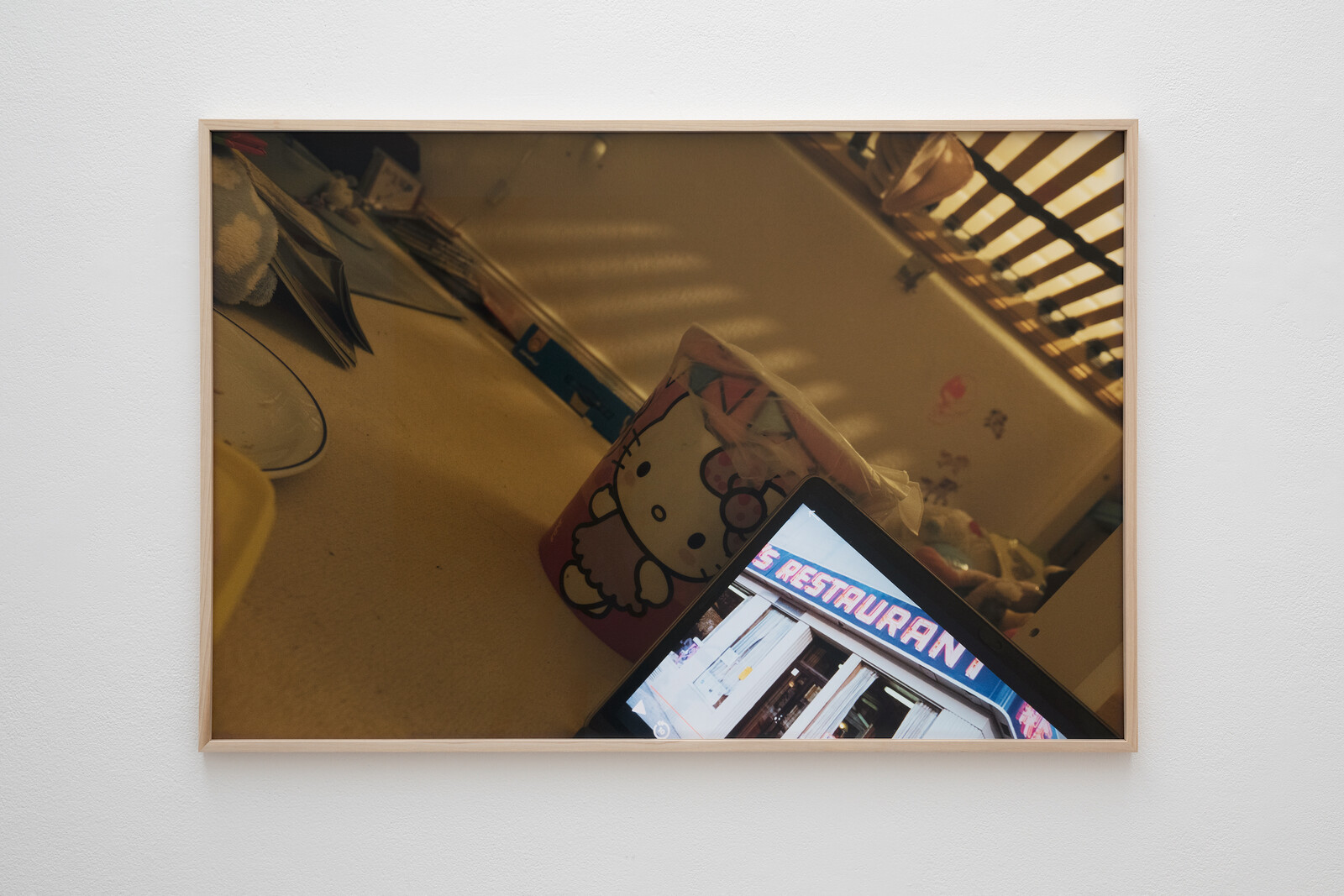

Informally composed, the photographs would be snapshots if they had a stronger hold on particular characters or occasions. As it is, they paint periods of relative stasis. How long did it take to make that cityscape out of building blocks? In one print, an image of Tom’s Restaurant in New York appears on the screen of a device on a carpet, next to a Hello Kitty mug and a crumb-flecked plate, like the projection of a housebound parent itching for a night out. The now-absent adult who was attending to a child as it ate on the floor must have been watching Seinfeld, which regularly includes scenes shot at Tom’s. In this winking aside, the artist suggests that in his world the singleton’s lifestyle is available only in the form of an entertaining fiction. A similar message is conveyed through the show’s title, “Solo Yolo,” which has to be read as ironic, or at least as knowingly contradictory. Yolo, short for “you only live once,” was a popular hashtag a few years ago, at a time when the artist may not have been a parent; in using it, Taleb is knowingly intimating that he is behind the times. To someone responsible for young children its implied injunction—go wild!—is in any case silly, while “Solo” points to the shrinking social horizons of parenthood.

Taleb’s shots conjure routines, intervals of unspecified length, periods drained of forward momentum. In places you catch a hint of boredom: that construction out of building blocks may be the work of a parent, not a child. There are signs of labor and distraction too, in the image of two desktop computer screens, for instance, one showing a livestreamed poker contest. Following the card game is presumably the indulgence of a telecommuting parent, who may be working on the other screen. The motif confirms an impression that runs through the whole show: what excitement there is in the family home is mediated, it comes in on broadband.

Taleb distends time—not just by picturing oases of stillness but also through repetition. The clearest example of this is a trio of pictures of different sizes, all showing the same bedroom at night. The lighting varies from image to image: green-tinged in one, it is purplish in the next, and dappled green and purple in the third. It takes a moment before you understand that this is a child’s room, lit by both streetlamps outside and a kaleidoscopic bedside light inside. There is no knowing when the photographs were taken, whether they were shot in quick succession or over a period of hours, even days, so the temporality of parental responsibility sketched here is loose. And this looseness is Taleb’s central concern, though “concern” is perhaps too pointed a term. His vision is milder than that, less obviously willed and organized.

Martin Heidegger illuminates this slack temporality when he writes, in The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics (1929–30), that boredom is the one condition that opens onto a clear consciousness of the passing of time. It is the absence of narrative drive, of tension or exchange, that gives Taleb’s work its distinctive time-tone. His perspective is neither nostalgic, though he hints at lost pleasures, nor entirely detached—the tenderness in the shot of the hands is plain to see. His work is best understood as a counterpoint to the images that circulate on social media. Where they are attention-grabbing, these pictures address us in a minor key. Where they communicate in the first person singular, these downplay the artist’s authorial presence. Above all, social media posts speak to a narrow present, whereas Taleb’s work details a more expansive time—not, or not just, a mindful slowness but the more ambiguous longueurs of creeping middle age.