On her first visit to Africa in the early 1970s, Angela Davis was surprised to find her speeches interrupted by dancing. Being pulled from the lectern whenever an idea moved her audience showed the philosopher and activist, she tells filmmaker Manthia Diawara in a work commissioned for the fifteenth edition of the Sharjah Biennial, how damaging is the western separation of intellectual speculation from embodied action. She proposes art as the form through which these two expressions of human freedom are reconciled. How it might do so is the question that haunts this sprawling exhibition of over 150 artists “conceived” by the late Okwui Enwezor and curated by Hoor Al Qasimi.

The difficulty is encapsulated by Diawara’s Angela Davis: A World of Greater Freedom (2023), which joins incendiary footage of Nina Simone singing “Mississippi Goddam” (1964) to Davis’s testament that the song did more to mobilize resistance than a thousand books. Simone’s performance leaves no room to doubt it, but the black box in which the film is screened leaves no space in which to dance it. Similarly, Bouchra Khalili’s The Circle (2023) combines accounts of the campaigns by which French-Arab workers asserted their rights in the early 1970s with dramatic monologues by the participatory theater group Al Halaka. Sitting on a semi-circular platform designed to resemble the amphitheater in which Al Halaka performed, it’s hard to ignore the fact there are few comparable opportunities here to unsettle the lines separating performance from dissent. And to reflect that this film, like Diawara’s, relies on archive material from the heroic era of protest to illustrate the capacity of art to effect change: is this what it means to “think historically in the present”?

Other standouts among the more than 300 works spread across five towns consider whether and how art might break the cycles that shape our historical moment. Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s Until we became fire and fire us (2023) transforms the ruins of a house in the reconstructed old town—itself an unsettling mix of temporal registers—into a series of rooms cast in cool sepulchral light by a canopy of purple fabric. Onto the walls are projected scenes of collective protest and communal release, their colours inverted like photographic negatives, that assert the freedom of a culture to express itself even under occupation. “We are the negative,” reads a poem printed on a plate of corten steel and hidden in a nook, “how many times have we died?” The irruption of the past into the present is literalized in Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s Under the Cold River Bed (2020), which tells how a Roman city was uncovered by a 2007 conflict in a camp for Palestinian refugees in northern Lebanon. Centred around three slide projectors, the work offers a reminder that historical complexity can be communicated in a tone that is not didactic and through forms that do not mistake technical convolution for intellectual sophistication. This sparse installation conjures the temporal and ideological confusion generated by war and displacement: a series of frayed timelines that crisscross and contradict each other.

If the attribution of the show to Enwezor might generously be interpreted as an act of curatorial self-effacement, then the exhibition is weakest when venerating his past achievements rather than adapting his thinking to the present. A number of new commissions by artists closely associated with the curator fail to scale the heights of earlier achievements. The romanticism inherent to the work of John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien shades—in their immersive, multi-screen video installations—into bombast. The restaging of Berni Searle’s Com-fort (1997/2022), commissioned for Enwezor’s Johannesburg Biennale, divorces the sculptural installation from the physical and political infrastructures from which the power of its critique derived. Carrie Mae Weems’s The In Between (2022–23), meanwhile, seems designed to resemble Enwezor’s pied-à-terre in the afterlife. Complete with blooming white orchids, piped spiritual music, and bound copies of the curator’s back catalogue, the homage only adds to the sense that the past might here be obstructing the birth of the new.

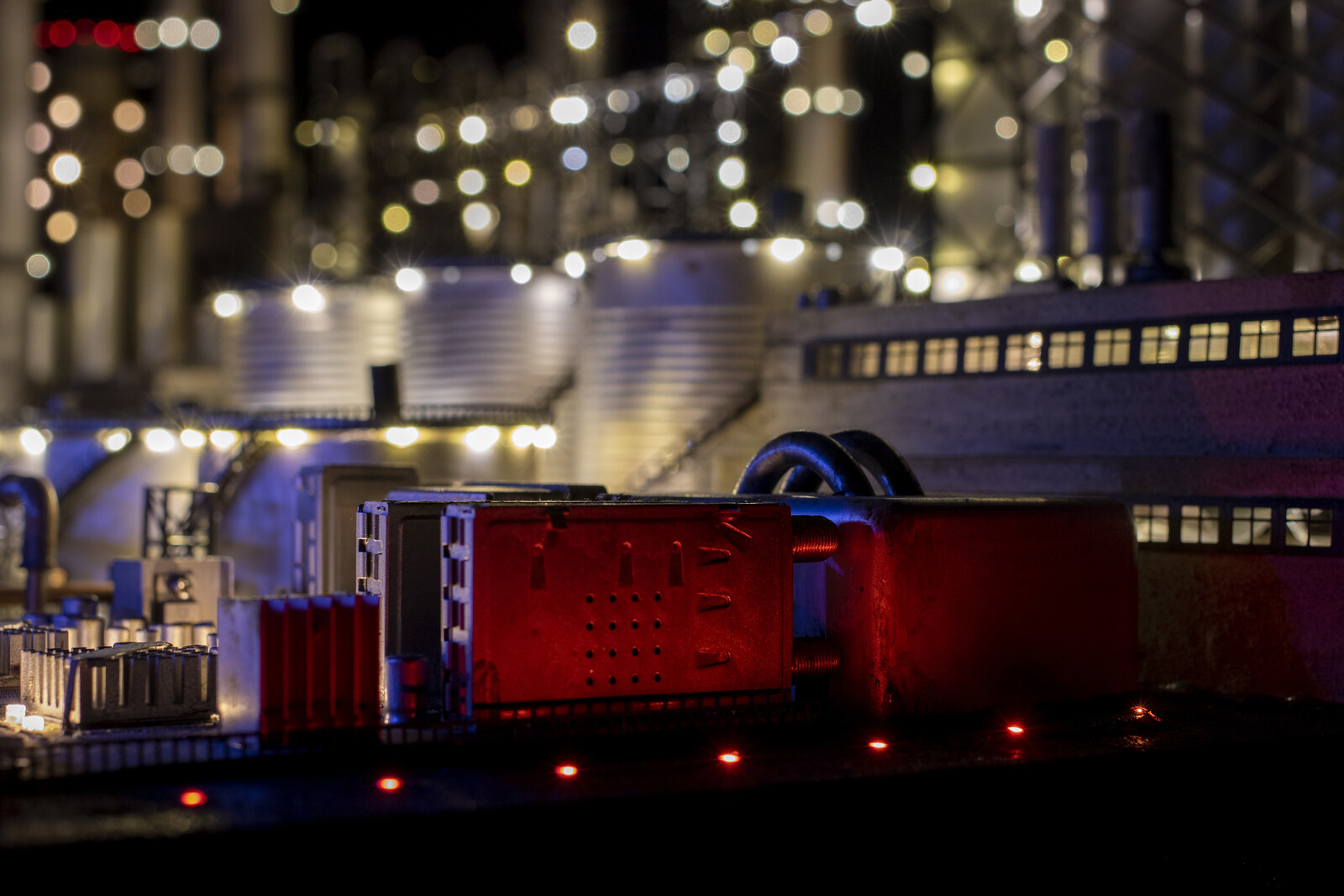

While Enwezor’s exhibitions frequently staged the consequences of slavery and colonialism in the cities built upon their profits, it can feel on occasion that the “deterritorializing” project outlined in the biennial’s curatorial statement has a hole at its center. There are powerful and intelligently chosen expressions of dissent from oppressed populations in Palestine, South Africa, South America, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Australasia, but these are rarely complemented by comparably direct engagements with the domestic and international impacts of Gulf politics. Fables and visions are mobilized as “paradigms of knowledge transmission,” and works including Farah Al Qasimi’s playful Um Al Dhabab (Mother of Fog) (2023) retell regional histories through encounters with historical artefacts or figures (the ghost of a pirate, in Al-Qasimi’s example). Yet the dangers of confusing fairytale with history are alluded to by Monira Al-Qadiri’s deceptively complex short film Crude Eye (2022), which connects the childhood dream of a marvelous palace to the illuminated oil refinery that inspired it.

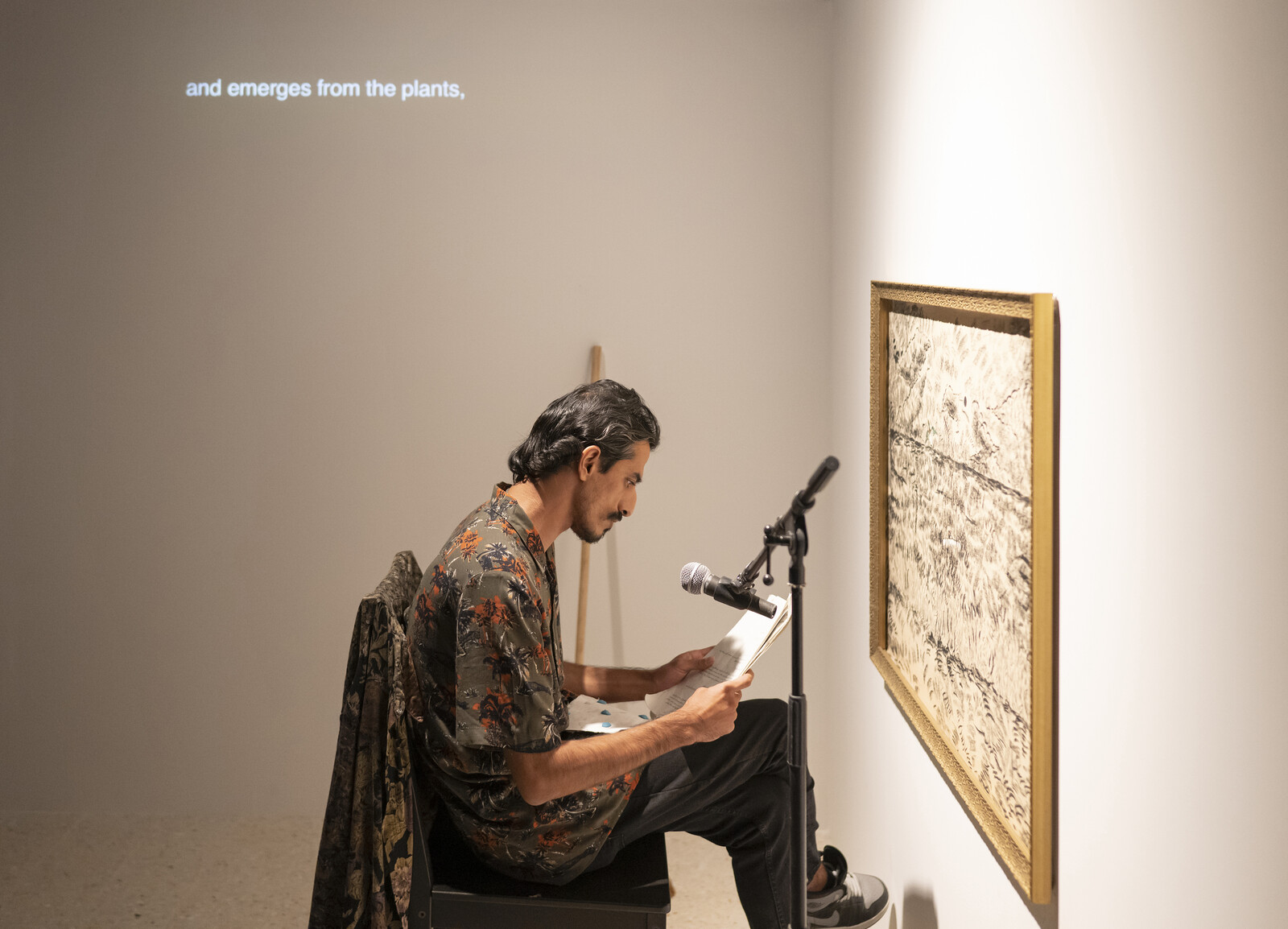

The exhibition is on firmer ground when the task of thinking historically is interpreted as the responsibility to bear witness to the present for the benefit of posterity. Mounira Al Solh’s A Day is as Long as a Year (2022) repurposes the embroidered tent of a nineteenth-century Qajar prince as a shelter for six heartbreakingly mundane stories of female subjection, writing their experience into a form designed to sustain the patriarchy. Hajra Waheed’s Hum II (2023) sound environment also functions as a living archive of women’s resistance by gathering songs from around the world. The suspicion that the vaguely devotional space in which it is housed might be trading in the same ecumenical transcendentalism that makes the Rothko Chapel so objectionable is dispelled by a pamphlet succinctly outlining the revolutionary histories of the songs—from Palestinian folk song to K-Pop—that are broadcast within it.

By stark contrast with these places of respite, Doris Salcedo’s monumental Uprooted (2020–22) sculpts several hundred dead trees into the imposing form of an uninhabitable house. It is chief among several works in the biennial which by dwelling on issues of migration and statehood might conceivably be interpreted—in a state which relies on foreign workers and restricts citizenship to a fraction of the population—as critique applicable to the place in which it is exhibited as well as other sites of inequality. In the context of a renovated ice factory on the fringes of a desert, the impenetrable thicket also suggests a more fundamental separation from home: the dying natural world closing in on itself, to the exclusion of humanity. In whatever context you read Salcedo’s work, its interpretation of the biennial’s title is shared by the best work in it: wake up and look around, because history is happening now, and here.