The world has experienced immense changes since the turn of the millennium, including the spread of neo-fascism, a deepening of the climate crisis, and advances in digital technologies. Yet one situation has remained consistent throughout that time: infernal war across the Middle East. Whether in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, or Yemen, the devastation these countries have experienced remains almost unfathomable to those living in the West. For much of this time, Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz has addressed the repercussions of these conflicts through a cross-cultural artistic practice rooted in processes of translation across mediums, disciplines, and national borders. At the same time, Rakowitz aims to engage with a history of the Middle East that expands far beyond the prevailing narratives of war and insurrection.

In an exhibition entitled “The invisible enemy should not exist” at New York’s Lombard-Freid Projects in 2007, Rakowitz used everyday materials from the Middle East, such as food packaging, newspapers, and cardboard, to make replicas of some of the nearly 7,000 cultural artifacts plundered from the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad following the disastrous US invasion in 2003. Versions of small statues, friezes, cups, vases, and more from ancient Mesopotamia were displayed in rows on wooden tables, accompanied by detailed labels in Arabic and English. Rakowitz’s current exhibition at Jane Lombard Gallery is a continuation of this project under the same title, although the objects on display are much larger. Specifically, they are reproductions of wall reliefs from the banquet room of a ninth-century BCE palace near Mosul in Iraq. Like the rest of the ancient city of Nimrud, the palace was severely damaged by ISIS in 2015.

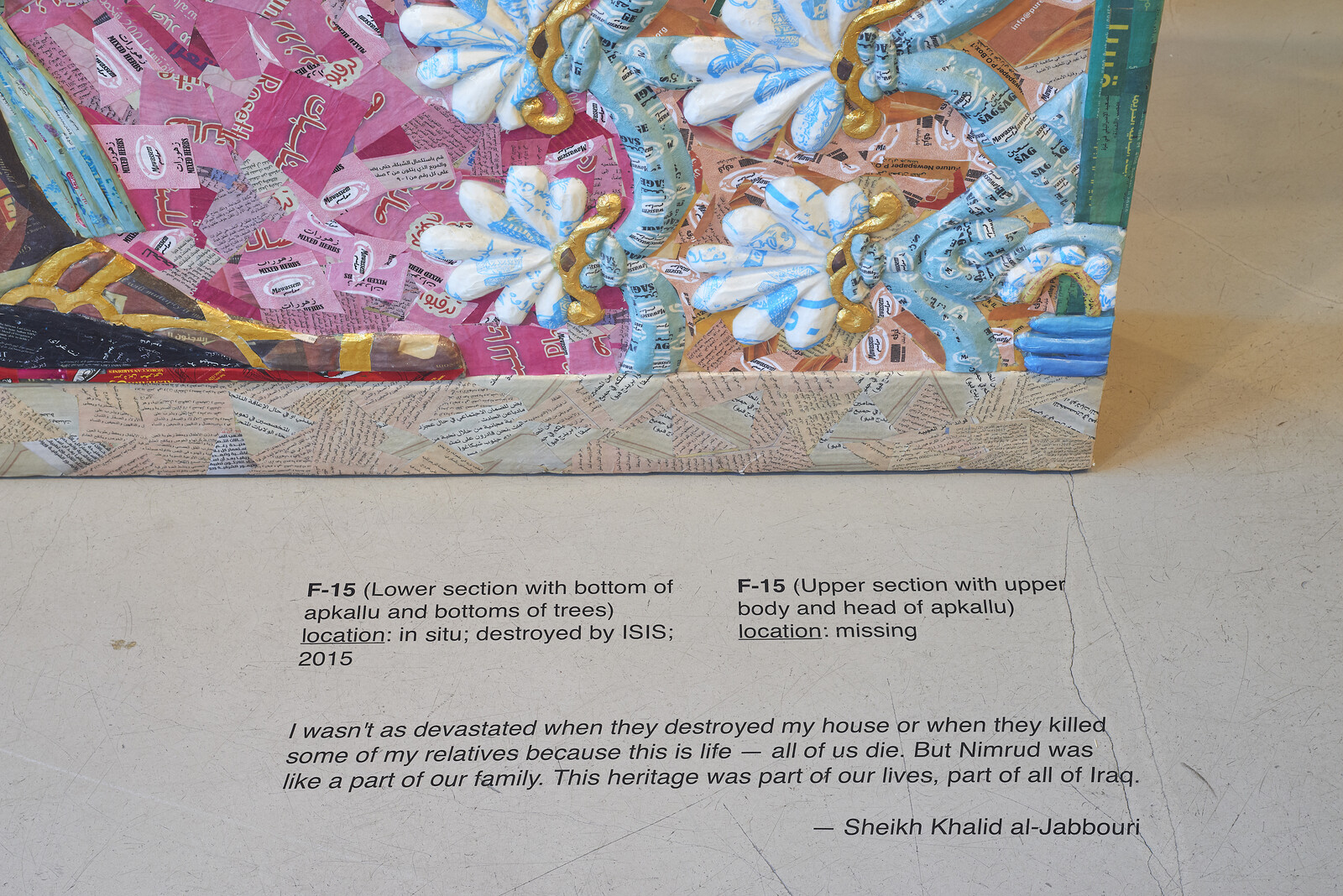

Each of the five freestanding wall-relief panels (all 2019) at Jane Lombard features palm trees and a latticework of flowers that together represent sacred vegetation within Assyrian cosmology. Two panels depict a figure—a semi-divine apkallu—with a human body, bird head, four wings, and carrying what looks to be a type of handbag, but is in fact a bucket. Two other panels consist solely of a palm tree and white flowers. The fifth is primarily a dense pattern of brown and dark gray portraying the scarred wall from which part of a relief has been removed. Again constructed from food packaging, newspapers, and cardboard, the panels are more than seven feet tall, with the largest more than seven feet wide. Rakowitz has rendered them in vibrant pinks, blues, greens, and whites: like ancient Greek statuary, the original wall reliefs were brightly painted. The panels contain replications of cracks running through them, evoking both their fragility and their age.

The five panels that Rakowitz and his group of fabricators (their names prominently listed at the entrance to the exhibition) have re-created for this exhibition were either destroyed by ISIS or have gone “missing”—most likely pillaged after 2003. The gallery remains more than half empty: sizeable gaps between the panels allude to other reliefs, previously removed—some might say stolen—from the palace by archeologists and excavators going back to the mid-nineteenth century. These were relocated to museums in the West, most prominently the British Museum, although artifacts from Nimrud can now be found in more than 75 museums around the world. Text stenciled onto the floor of these empty spaces indicates the reliefs’ fates, including year excavated and year acquired by an institution, followed by a quote from a contemporary Iraqi or earlier archeologist reminiscing about the site.

Rakowitz’s video The Ballad of Special Ops Cody (2017) is projected in the rear gallery. Its protagonist is a plastic military action figure, animated by stop-motion technology, who attempts to liberate a dozen or so small, ancient Middle Eastern statues from a display case in the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. By the end of the nearly fifteen-minute video, the doll—voiced by a US Iraq-war veteran—has taken its place among its sold and stolen brethren. That the action figure is African-American amplifies the historical resonance.

Although not a traditionalist, Rakowitz seeks a continuity in history that global capitalism—assisted by the nation-state war machine—would prefer to destroy, as would various fundamentalisms, including western ones, when confronting a history other than their own. The net of cultural annihilation has been widely cast, and Rakowitz seeks to counter this by drawing from the past in order to point toward a more survivable future. He does so, both in the ongoing, multi-component “The invisible enemy should not exist” and in his public art projects involving food trucks and import services, by instigating dialogues among diverse groups and institutions. His aim remains not to collapse difference but to highlight the difficulties and rewards in negotiating it.