In 2001, Maurizio Cattelan invited a group of the 49th Venice Biennale’s VIP guests to join a satellite event in Palermo: a cocktail reception in Bellolampo, the city’s main landfill, where the artist had installed a larger-than-life replica of the Hollywood Sign overlooking the Conca d’Oro, the defaced coastal “golden bowl” once filled with citrus groves. It was a vitriolic triumph of trash and a homage to the fictionalization of “a city that has to struggle every day with its own conceptions of its past and present,” the artist said.1 A few months later, Diego Cammarata, the candidate from Silvio Berlusconi’s party Forza Italia, won the local elections. His victory ended the long tenure of Leoluca Orlando, who during two nonconsecutive terms as mayor between 1985 and 2000 championed the anti-mafia movement known as the Palermo Spring.

Seventeen years later, Orlando is back in the mayor’s seat for the fifth time, as leader of a center-left coalition; a new biennale has landed in town; and another work—art collective Rotor’s installation Da quassù è tutta un’altra cosa [From up here, everything looks different] (2018)—invites viewers to visit another devastated hill perched atop the city. Nicknamed “the hill of shame,” the Pizzo Sella is home to 170 aborted villas built by the mafia before being sequestered (but never demolished). On the walls of these modern ruins, which offer panoramic views of the Gulf of Mondello, in 2013 the Palermitan art collective Fare Ala created the Pizzo Sella Art Village by covering the empty concrete skeletons with graffiti. Another Grand(iose) Tour of contemporary ruins is provided by Alterazioni Video. Since 2006, the collective has mapped and catalogued Italy’s more than 700 incomplete buildings (250 of which are in Sicily), putting forth a theory of the stile incompiuto, or unfinished style, as the most significant architectural vernacular of the Bel paese. Their research on this perennially deferred modernity—displayed at the photography center run by Letizia Battaglia at Cantieri Culturali alla Zisa—is included in the “Palermo Atlas,” a comprehensive urban study of Palermo carried out by OMA for Manifesta 12 and published as a book for the occasion.

And yet the do-good tale spun by this biennale (signed by a group of four “cultural mediators”: journalist and filmmaker Bregtje van der Haak, architect Andrés Jaque, Sicilian-born architect and OMA partner Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, and curator Mirjam Varadinis) is not one of decadence and nostalgia, but of revitalization and care, despite old problems and new emergencies. Manifesta has again moved to Southern Europe under the hopeful title of “The Planetary Garden. Cultivating Coexistence,” inspired by radical gardener and botanist Gilles Clément and Sicilian syncretism. In recent decades, Bangladeshi, Tamil, Ghanaian, and Chinese communities have moved into Palermo’s historic center, next to the UNESCO Arab-Norman heritage sites. Meanwhile the Charter of Palermo, signed in 2015 by the UN’s International Organization for Migration, demanded recognition of international mobility as an inalienable human right. The city, which this year is also the Italian Capital of Culture, is clearly assessing and promoting itself as a “capital of cultures”—and a liberal one, when compared to the urban and political contexts of St. Petersburg and Zurich, where the two most recent iterations of the self-proclaimed “European Nomadic Biennial” took place. Culture has always been a key factor and political tool for the EU and, as a seasoned politician, Orlando is aware of it.

Manifesta 12 has positioned its headquarters in the historic Piazza Magione in the Kalsa area (an ancient Arab quarter near the promenade of Foro Italico, reclaimed from the ruins of World War II), and more precisely in Teatro Comunale Garibaldi, reopened in 2017 after its occupation by a collective of theater workers. The main venues of the exhibition are chapels and palazzi (Butera, Forcella Da Seta, Ajutamicristo, Costantino, Trinacria) owned by civic authorities, noble families, and powerful collectors, currently undergoing renovations often underwritten by European and Italian public funding. While the overall feeling is of the inner city being recolonized and gentrified, these grand venues form an itinerary of enchanted ruins, secret gardens, and usually inaccessible places of wonder, and will be further expanded by more than 70 collateral events that will unfold through November. Of these, two in particular stand out. Protocol no. 90/6 (2018), an installation by Italian duo Masbedo at the State Archive, features a video of a pale, frowning pupo (puppet) in a blue jacket shown on a giant LED screen and surrounded by thousands of folders and records covered in dust, mold, and rat bites. Meanwhile, in the rooms of the Grand Hotel et Des Palmes, artists Luca Trevisani and Olaf Nicolai have curated “Raymond,” a secretive infiltration of events, performances, and artworks by international artists in homage to the dandy poet and novelist Raymond Roussel, who died at the hotel in 1933.

With a conscious nod to the Insta-friendliness of Palermo’s grande bellezza and the experiential lures of cultural tourism, one of the three sections of Manifesta is titled “City on Stage.” In it, a personal favorite is Jordi Colomer’s video installation New Palermo Felicissima (2018) at the Fondazione “Casa Lavoro e Preghiera” Padre Messina, a former orphanage overlooking the Caletta Sant’Erasmo, a tiny harbor used by local fishermen. It conveys, with a healthy dose of humor, the sense of disorientation induced by the anthropological agenda of much contemporary art. On the screen, a small group of people move by boat along the city’s Costa Sud. A young guide, played by actress Laura Weissmahr, offers information about the surroundings with a tentative Italian accent—she is in fact repeating lines from a text by writer Roberto Alajmo, dictated to her by earphones. Fiction, oral history, a temporary community of voices and bodies, and the undulating perspective of those who look at a land from the water subtly come together.

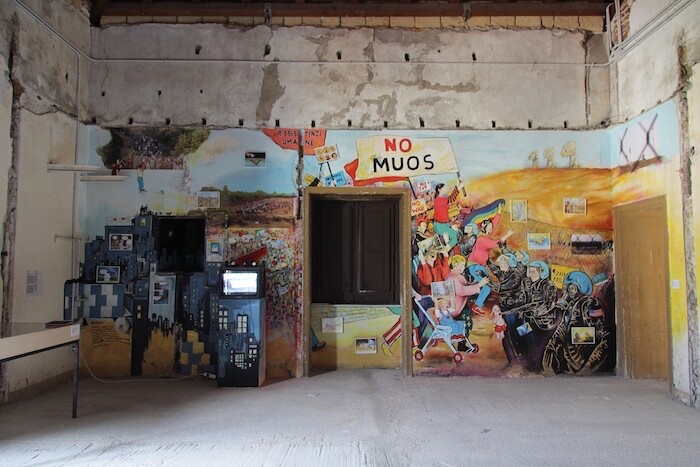

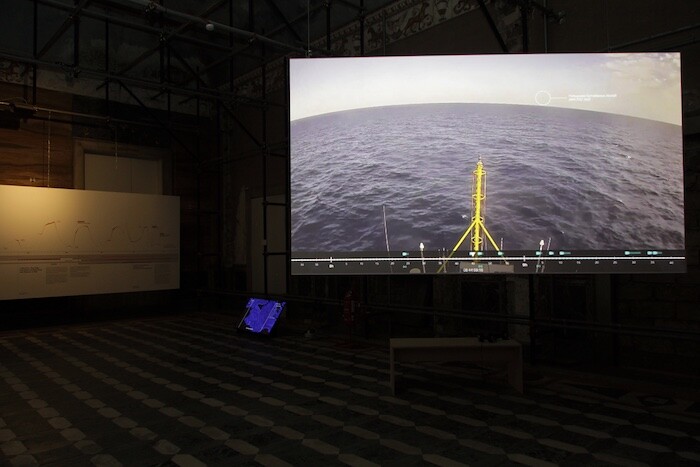

Sicily is the largest island in the Mediterranean. In 2018, themes of migration by sea, human trafficking, and technology-infused border control are very much on its map. They inform “Out of Control Room,” another of the biennale’s main sections, which features the video installation Signal Flow (2018) by Laura Poitras (shot in collaboration with Rome’s Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia) and Tania Bruguera’s installation Article 11 (2018), which documents the Sicilian political movements opposed to MUOS, the US Navy’s new global communication satellite system in Niscemi, in the southern end of the island. Concurrently, John Gerrard’s chilling simulation Untitled (near Parndorf, Austria) (2018) digitally reconstructs the titular portion of Austrian highway where a truck containing the corpses of 71 migrants was abandoned in 2015, while Forensic Oceanography’s striking video installation Liquid Violence (2018) investigates how the Mediterranean’s increasing militarization impacts the rising numbers of deaths among migrants. The work reminded me of Solid Sea, a research project started by the Multiplicity collective after the death at sea of almost 300 people and presented at Documenta 11 in 2002. Decades change, but so-called emergencies don’t.

A few days before the opening of Manifesta, Italy’s new interior minister, Matteo Salvini—who learned well (via Steve Bannon) the Trumpian “shock and awe” strategy of occupying public debate with racist discourse and violent tones on a daily basis—banned the Aquarius, an NGO ship carrying 629 migrants, from Italian ports. Orlando, meanwhile, announced that Palermo would receive it. (The boat was later accepted by Spanish authorities in the port of Valencia.) As instinctive as it is to side with Orlando and Manifesta’s engagé stance, I wonder if the frequently literal focus on migration risks further polarizing the issue, mirroring populists’ obsessions rather than embracing complexity. Among those works that address the subject more subtly is Algerian-born artist Lydia Ourahmane’s The Third Choir (2014). This sound installation is composed of 20 oil barrels that she struggled to import from the Algerian company Naftal to Europe. Each barrel holds a cellphone broadcasting fragments of sound pieces recorded in Algeria. It soberly attests the movement of bodies across borders by being the first artwork to be legally exported from Algeria since 1962, because of its restrictive legislation on the circulation of art.

The third section of the biennale is titled “Garden of Flows,” in accordance with Palermo’s luscious nature and exotic resident plants, such as the gigantic ficus macrophylla, an evergreen banyan tree presiding over Piazza Marina like a vegetal cathedral, or the magenta bougainvillea lining the streets. One of its main venues is the peaceful Orto Botanico. In the greenhouse, Alberto Baraya installed among the living plants his own herbarium, New Herbs from Palermo and Surroundings. A Sicilian Expedition (2018), which gathers artificial botanic samples collected from flower offerings all over the island. Zhang Bo positioned the video screen of his Pteridophilia (2016–ongoing) amid the trunks of a bamboo grove. In order to see it, viewers have to peep across plants. It is one of the most captivating and least comfortable works on show: a declaration of eco-queerness in which the artist portrays sensual interactions between naked young men and a forest of ferns. The duo Cooking Sections built simple structures around different trees scattered in city gardens and the open-air Chiesa Santa Maria dello Spasimo, to study how stones can be used to combat desertification, while Renato Leotta’s minimalist installation Notte di San Lorenzo (2018) evoked the slow falling of fruits of the ground in a citrus grove, by replicating their round marks imprinted on the maiolica tiles that cover an entire floor of Palazzo Butera.

Leotta is the only Sicilian artist invited to participate in Manifesta, which raises questions of institutional ecology. How polycultural can a biennale be? For how long will it fertilize the local scene, its museums and independent spaces? For how long will the community garden created by Coloco and Gilles Clément in the dilapidated Zona Espansione Nord (ZEN) keep on existing? Cultivation notoriously requires time, while the pace of communication is fast. The biennale’s opening performances—Matilde Cassani’s Tutto, (2018), which recreated the explosions of confetti and frenzied drumming that marks the festivities of Santa Rosalia, and Marinella Senatore’s Palermo Procession (2018), which brought together dance and activism—offered moments of epiphanic magic and provisional joy. Time will tell whether such celebratory moods can endure. Over the last weekend, an editorial published by Italian journalist Antonio Polito in the newspaper Corriere della Sera pondered the end of Italian buonismo (do-goodism), which naively oversimplified reality but relied on the construction of an inclusive culture, and the contrastingly rampant growth of cattivismo (do-badism), which enhances negative behaviors, divides the world into friends and enemies, and spreads the disruption of the common good.2 In times of trouble, we should recall Voltaire’s Candide (1759). After all, il faut cultiver notre jardin.

Nancy Spector, Maurizio Cattelan: All (New York: Guggenheim, 2011), 112.

Antonio Polito, “Il buonismo è finito. Ma il cattivismo di Salvini è meglio?,” in Corriere della Sera, June, 17, 2018, https://www.corriere.it/politica/18_giugno_18/cattivismo-leader-che-riduce-7683dcde-726b-11e8-845f-3f4efe05492d.shtml.