Along their descent down the ramp into the MAAT’s ovular, central exhibition space, visitors encounter a series of angular, austere, and imposing structures that are formally reminiscent of military architectures. Like medieval castle walls, with embrasures mediating the simultaneous necessity to look out while not letting anything in, gaps between the structures obstruct and frame views into a brightly illuminated, enfilade-like space. The perceptual logic of concealment and revelation is carried further by a series of circular cuts made to the structures’ inward-facing walls that confess their hollowness while presenting a panoply of material from the architect/artist’s dynamic, evolving, and multifarious practice.

Over the nearly thirty years covered by this mid-career retrospective, Faustino has worked with buildings, installations, furniture, prosthetics, video, photography, speculative design, performance, and more to confront and transform the normative limits of architecture and the body, which, as his work proves, inextricably condition one another. This is evident in Asswall (2003), which creates a literal hole in a wall the size of a single body, and Home Suit Home (2013), which refashions stiff carpet into a garment for the body. But it is perhaps best demonstrated by the scale model of One Square Meter House (2001–06), a seventeen-meter-high structure with a one-square-meter footprint that provocatively questions the minimum amount of space that might be needed to live. While originally created as a critical response to speculative real estate practices, the conceptual affinity between One Square Meter House and Absalon’s Cellules (1991–92) allows us to read an additional, subversive layer of meaning in Faustino’s work: inhabiting an architecture which is defined by and defines the limits of one’s body might actually be a transcendental, emancipatory experience.1

Like laws, limits are often virtual, with their power only becoming real when certain thresholds are crossed. But these thresholds are not always evident or known; they must first be discovered. “Exploring Dead Buildings” (2010, 2015) maps out and explores the relations between bodies and different canonical, abandoned works of architecture through the use of performative, mediatic apparatuses such as a cage that hangs over the body and a kart-like motorized vehicle. Yet not all limits are designed, human, or otherwise “constructed.” Opus Incertum (2008), for instance, builds the empty space into which Yves Klein launched his body in search of freedom and abandon in Leap into the Void (1960). By placing one’s body in the same position as his, one feels not only the weight of gravity, but in its clunky confrontation with the wooden artifact, also the pain of temporarily suspending it. Once limits are identified and understood, however, to approach, reach, or even transgress them can be a sublime and deeply pleasurable experience. This becomes most clear in Doppelgänger (2011), a 3D-printed artifact shaped to fit two people’s faces that brings them together for a kiss—their heads slightly tilted to opposite sides—yet ultimately prevents intimate contact, thus charging the state of close proximity and sublimating desire.

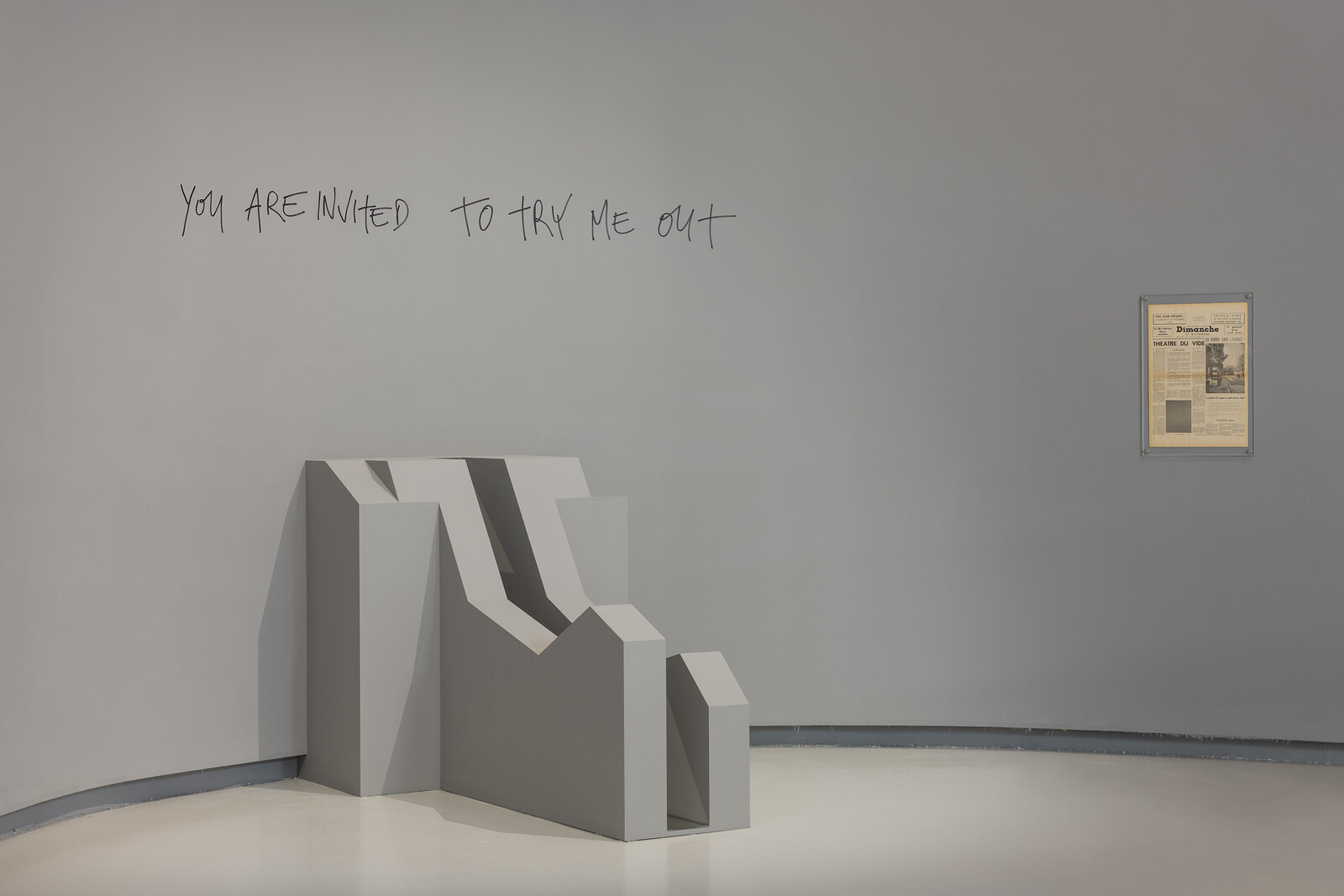

A complementary strand of Faustino’s practice explores the potential violence and inherent power of domestic and other design objects. Love Me Tender (2000), for instance, is a chair made of stainless steel whose tube legs are whittled down to meet the floor in sharp points. Threatening to penetrate the surface of whatever lies beneath, concentrating the weight heightens the agency of whatever sits on top. Other chair works, such as Tetsuo (2012), resist the furniture type’s normative functionality by providing an armature for sitting without it being clear exactly how one is supposed to sit, or how the chair itself is supposed to stand. The idea of a non-normative design is carried even further by Intruder C (2021), an awkward multicolored steel tubular object whose form resists any conventional mode of usage and demands to be discovered through experimentation. Dismantling the power of design objects is made most explicit in his series of works with steel barricades, such as BUILTHEFIGHT (2015) and Untitled (2019). Most commonly used to control crowds and police public space, the power of these objects can be formally manipulated, recomposed, and deployed towards other, more sublime and emancipatory ends.

Curated by Pelin Tan, the fifty or so works on display in the central hall and a smaller side room represent just a fragment of Faustino’s oeuvre, as well as that of his architectural studio, Bureau des Mesarchitectures, which also designed the exhibition. It is unfortunate that the relationship between Faustino and his studio is left unresolved within the exhibition, given that Faustino (or his studio?) has been increasingly realizing more permanent buildings and other architectural spaces, including interiors, houses, apartment buildings. While it is clear that Faustino’s practice as an artist is informed by architecture, it would have been relevant to focus more on the opposite trajectory of influence. Faustino understood early on that artistic practice provided him the opportunity to more practically engage with concepts, questions, and concerns that are inherent to architecture such as norms and normativity, comfort, and desire. What is not entirely evident in the show, however, is how—and to what extent—his critical agenda towards space, design, and bodies might become operative in architectural practice. Yet what Faustino’s practice teaches us is that to identify a limit is to act upon it. To formalize limits is to render material their power, and demonstrate that it is always capable of becoming something else.

Absalon, “Lecture: École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, May 4 1993,” reprinted in Absalon, ed. Susanne Pfeffer (Cologne: KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2011), 255–73.