I’m leaving New York in a month. The other night I told that to an acquaintance who asked if I had read Goodbye to All That (2013), a collection of writing about “loving and leaving New York.” I’ve only read the 1967 Joan Didion essay that gave the book its title.1 A friend suggested we go to the used bookstore around the corner. “They probably have a shelf dedicated to it,” I said.

“You see I was in a curious position in New York,” Didion writes: “it never occurred to me that I was living a real life there.” She came for a few months and stayed for eight years. I came with an intention to stay, but “a real life” is elusive or impossible under the current political system. The third iteration of Condo New York, an initiative begun in London in 2016 in which local spaces host visiting galleries, opened in the same month MoMA closed for renovations as it soaks up the building of its displaced former neighbor the American Folk Art Museum, and in the same week I skipped an opening at the New Museum because I didn’t want to cross the picket line of its employees rallying the museum to negotiate with the union they voted to join. The real life of an art institution, some would say, involves looking away from the “defense technology” company the vice chairman of your board may own. A project like Condo, the reality of which is traveling with small drawings and video work to show in a different city and expand your collector base, can be a reminder of the role galleries play in the art ecosystem, for artists and collectors, yes, but also visitors and one another. Eighteen New York spaces—including nonprofit White Columns, hosting Visionaries + Voices, an artist-run space in Cincinnati dedicated to artists with disabilities, showing paintings and sculptures by Curtis Davis—are hosting 20 others.

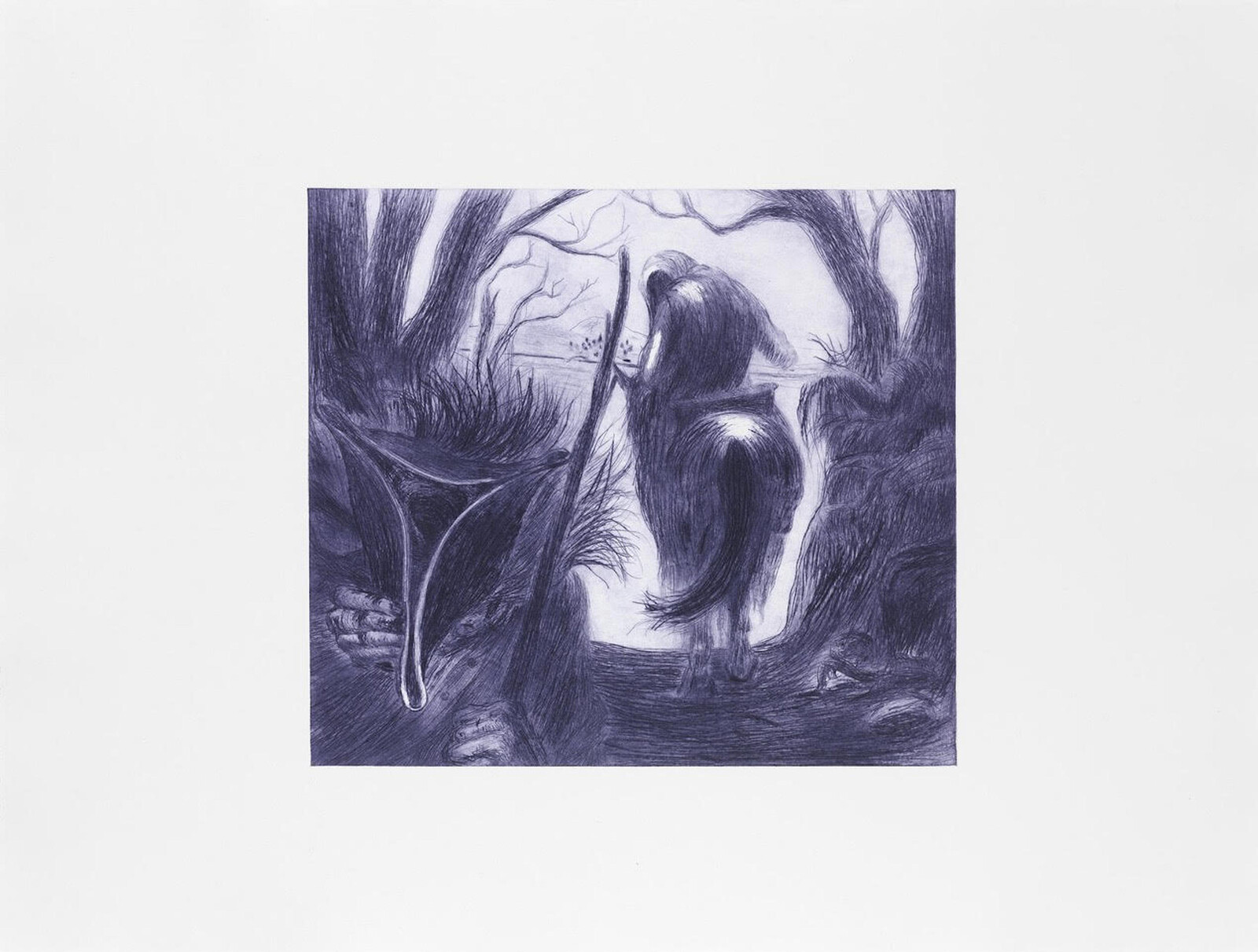

Several exhibitions cohere as group shows. At Queer Thoughts, hosting dépendance from Brussels, an aquarelle on canvas by Sofia Duchovny, Heart Shaped Box (ripped) (2019), makes this 1990s object into the subject of a sorrowful narrative. Next to it is an acrylic on paper of a bird (Toucan, 2019) by Genoveva Filipovic and an untitled drawing by Peter Wächtler (2018) of a figure on horseback going through a dark wood. The three works are not fully representative of these artists’ practices, yet together feel like a lucid group show of contemporary drawing. (There’s also a monitor with a funny short film, Mayonnaise Number 1 [1973], by Charles Atlas of a model pretending to be in a Renaissance portrait only he eats the fruit, breaks the pose, ruins all illusion.) Lomex—named after an urban planning proposal by Robert Moses, the man who imagined New York City as a collection of highways, called Lower Manhattan Expressway, which luckily was never realized because it would have razed much of the Bowery area in favor of a road—hosts O-Town House from Los Angeles, exhibiting little drawings by Gerry Bibby (Note to Self 1, 2, and 3, 2019) printing tiny poems and scribbling notes on found envelopes. They’re framed like family photos and placed on the mantelpiece of the gallery that kept its apartment layout (which used to be Eva Hesse’s studio), a small gesture that allows viewers to stop and read before looking at louder work like John Boskovich’s framed pink bumper stickers reading messages like Screw Guilt and Reality: What A Concept (both 1997).

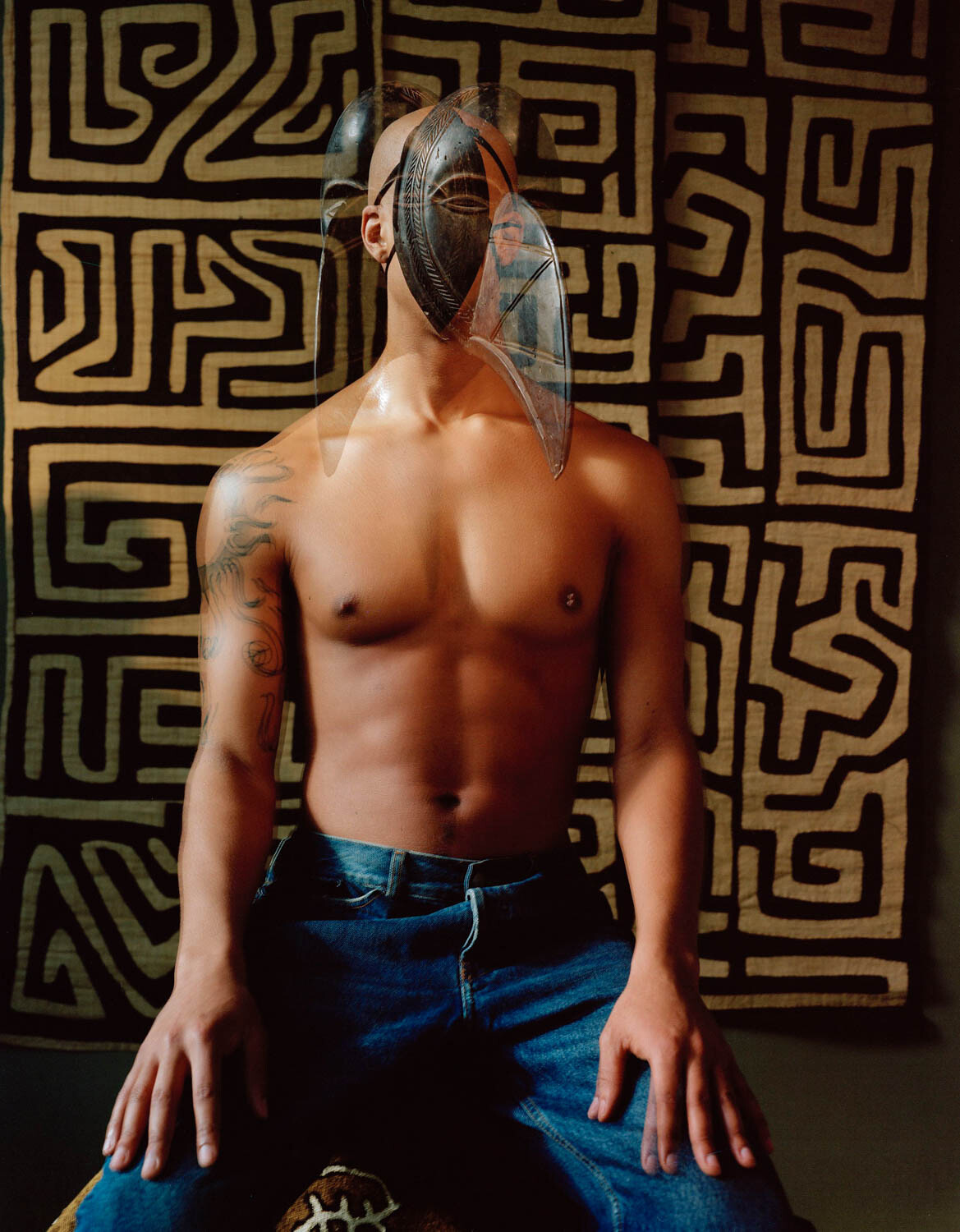

Chance meetings happen across Condo. At Company, two artists who graduated a year apart from Yale with MFAs in photography are showing in the gallery’s two spaces. At the main gallery on the Lower East Side, photographs by John Edmonds merge portraits with West African sculptures; Two Spirits (2019), in which a bare-chested man wears an African mask, feels like a re-appropriation of Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) in MoMA’s collection. Around the corner at Baby Company, Commonwealth and Council from LA present David Alekhuogie, whose photographs repurpose flags to pay tribute to African-American quilting. Chapter NY hosts London gallery Emalin: two paintings by Paul Heyer, Summer Fruit and Broom Tree (2019), in shades of blue and purple that are much darker than the titles suggest, hang by two photographs from Bruce LaBruce and Kembra Pfahler (Wall of Vagina I and II, 2004/18) drawn from a photo of three stacked naked bottoms that Pfahler remembered seeing in a porn mag, and three drawings by Pfahler (Wall of Vagina Study I, II, and III, 2019) made for the show in pen, acrylic, and glitter. The works come together formally, in their purple and black colors, and conceptually, in the fact that this departure from what a regular visitor to Chapter NY would usually expect from the gallery’s program is still presented in a restrained exhibition of only seven two-dimensional works.

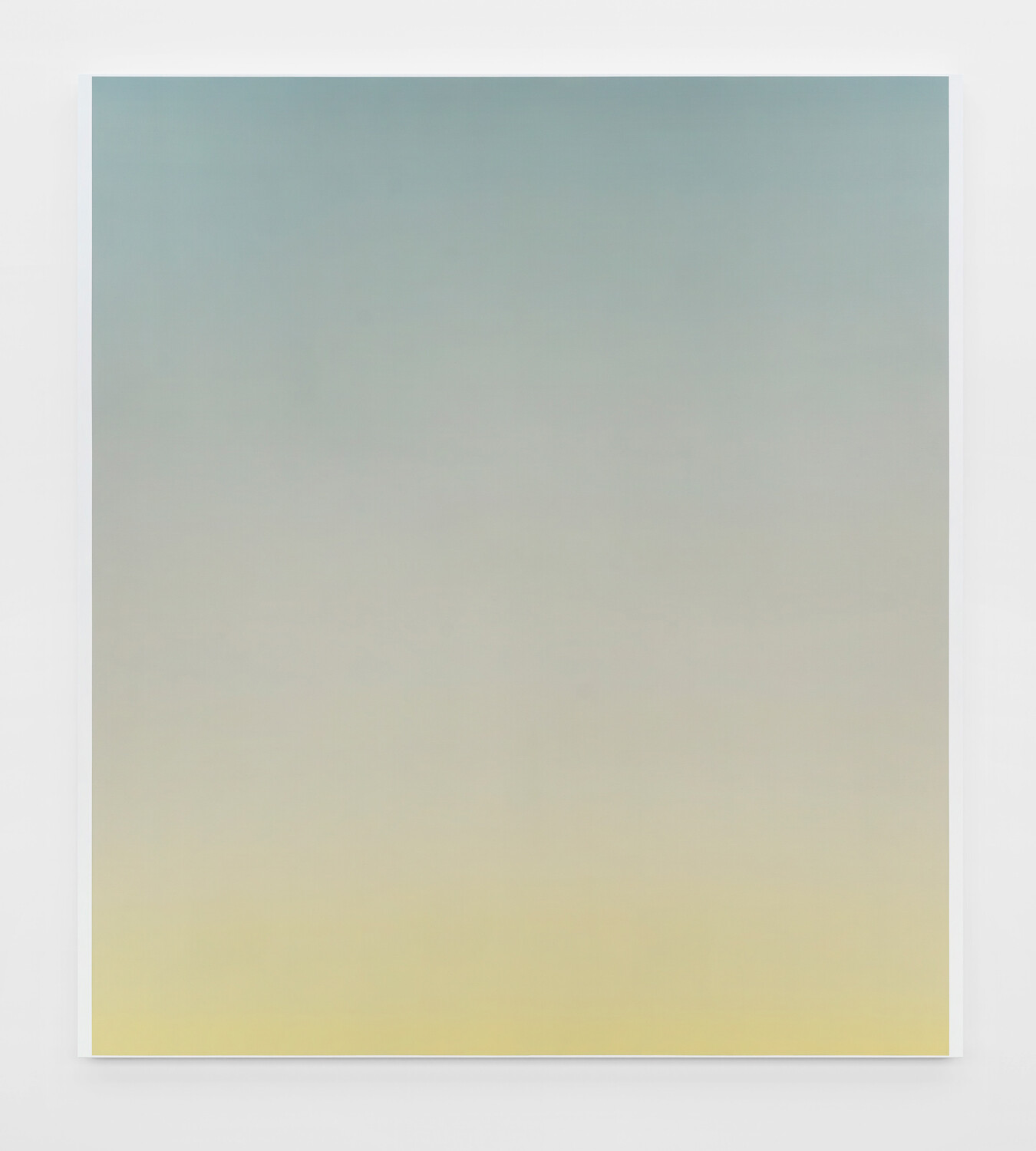

Coherence, though, isn’t necessarily what makes a good Condo project. Several galleries simply handed over their spaces or parts thereof. In Chelsea, Metro Pictures gave its upper floor to Glasgow gallery Koppe Astner, showing Miguel Cardenas, who makes the most of the space with murals on both ends of the wall leading to it, framing his small landscape paintings and sculptures on pedestals. In Tribeca, Bortolami is hosting Paris gallery Jocelyn Wolff, with works by Katinka Bock, which echo the sculptures of Ann Veronica Janssens in the main space. But where Janssens spills glitter on the gallery floor (Untitled [White Glitter], 2016–ongoing)—accompanied by a warning not to step on it—Bock covers her part of the gallery with fine rocks (Sand, 2018). Treading on it, Bock’s show feels foreboding, intense, grating, and much more effective. Uptown, Petzel gave its Upper East Side location to Edouard Malingue Gallery from Hong Kong, showing gradient paintings (Vertical Gradient #1–8, all 2019) by Chou Yu-Cheng that look like they were made digitally by simply reproducing Photoshop’s color palette but are actually handmade abstractions in a refusal of the expected. In the other room is Soliloquy (2018), an installation by Indonesian collective Tromarama composed of lamps linked to binary code that commands them to light up whenever a Twitter user posts something with the hashtag “kinship.”

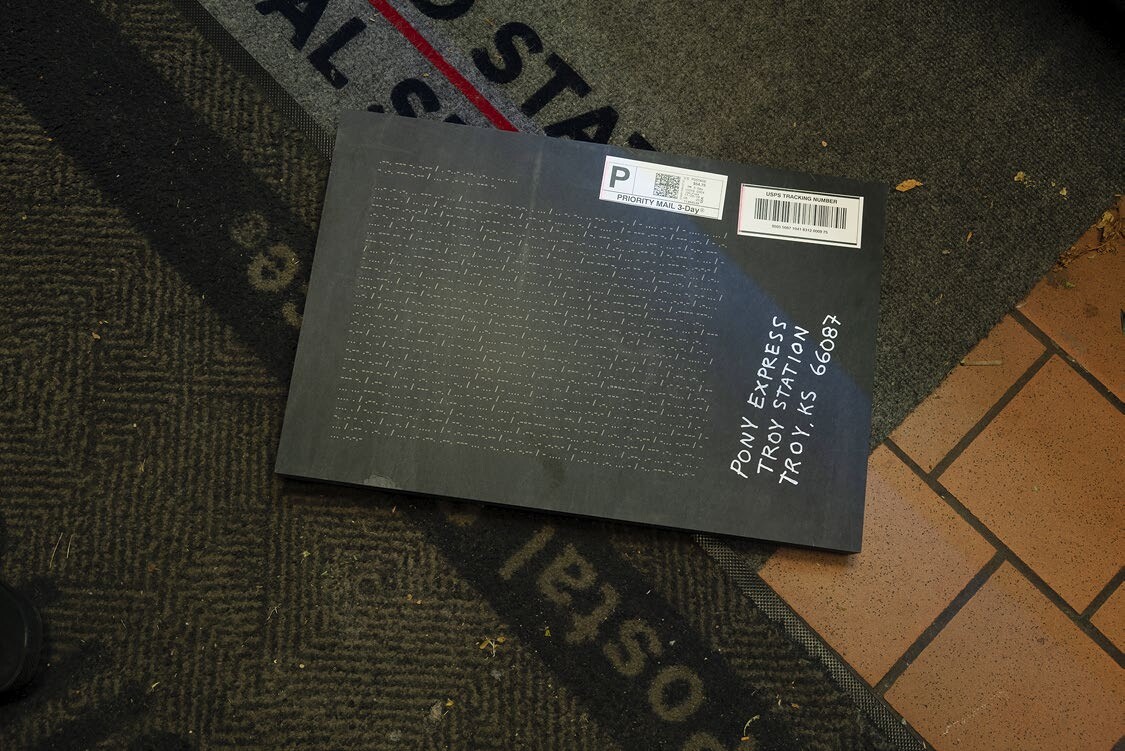

On the subway ride to Petzel, I reread Didion’s essay and couldn’t help but smile, sometimes laugh—“Was anyone ever so young?,” she writes of her first days in town. When I look back at a decade in New York—the galleries where I never missed a show, the galleries I loved and closed, the museum exhibitions that formed me and the ones I accidentally skipped (and sometimes still pretend I didn’t)—what comes through is the works of artists that stayed with me. I discovered new artists at galleries I’ve been to before: José Manuel Mesías at Lubov (brought by Apartamento, Havana), Maria Montero at Simon Preston (hosting Sé from São Paulo, where Montero is the director, a brave and conscious reflection of how different ways to participate in art can collide). And some of my favorite pieces were by artists I already knew, like Filipovic’s work, which I haven’t seen in years though I thought about it often, only to encounter a small drawing of a toucan, complicating what I thought I remembered from other shows of hers. At Simone Subal, two pieces by Frank Heath, whose work I’ve seen at the gallery before: Fixed Window (2011), a 38-minute sound piece in which a man calls numerous businesses recounting how overnight someone replaced all his windows with stone slates, is accompanied by a sculpture of a stone slate encased in glass. On the phone, he tries to explain what happened. “That’s strange, very strange,” a woman at a glass repair shop says. “I believe you,” she confirms. “Numbers Station for The Pony Express” (2018) are two photographs of slates sent through the US Postal System laser-etched with information in Morse code about the stations of The Pony Express, a relay horseback mail-delivery system between Missouri (it originated in Heath’s hometown) and California, which lasted only a year, between 1860–61. The sculptural objects are postmarked to the defunct Pony Express stations. The two works are related: both involve sending something—an object, an idea, a call for help—out into the world, knowing it’s bound to be lost.

Didion’s essay begins with the line, “It is easy to see the beginning of things, and harder to see the ends.” I reviewed the first iteration of Condo, in London in 2016, and I was wrong about so many things then. Then it was new. Now, like the condominiums it was named after, this project pops up everywhere, in cities where rents are rising, where it’s ever harder to keep going. Then, I thought that to be meaningful, Condo had to make connections and form shows that cohere; I thought it was in desperate need of a curator. Now I see—introspection—the meaning is in looking (back) at a place and seeing it for all it has to offer.

All quotes in this review are from Joan Didion, “Goodbye to All That,” in Slouching Towards Bethlehem (New York: FSG, 1968), 225–238. Reprinted in Sarri Botton, ed., Goodbye to All That: Writers on Loving and Leaving New York (Seattle: Seal Press, 2013).

%20©%20Marius%20Land.jpg,1600)