In the wing mirror on the passenger side of a vehicle, objects are closer than they appear.

The texts republished in the Rearview series are those that we wish to draw attention to because they reveal certain “blind spots” in contemporary art criticism. These “found” documents (indeed, quasi-artifacts) are prefaced by one of our writers.

Mary Josephson is, to my knowledge, the first fictitious female art critic conceived of by a man. She is one of Brian O’Doherty’s four, otherwise male, alter egos, among them the (by now late) artist Patrick Ireland. Josephson was born out of lack. Becoming the editor of Art in America in 1971, O’Doherty needed authors to write for the publication he was going to reinvent. Apparently, he made some of them up. That he decided on one female moniker is due to his lifelong fascination with fluid gender roles: “There is a deep curiosity, and certainly I have it as to the nature of the other, the ultimate, that other, the other sex.”(1) The name itself, Mary Josephson, is a twist on O’Doherty’s upbringing in a stoutly Catholic environment.

Writing under a pseudonym comes with a great deal of freedom. Josephson surely thought outside the box, and so she devoted her first contribution (March/April 1971) to architect Morris Lapidus. Labeling him “the builder of kitsch hotels,” she nonetheless suggested him for serious cultural debate: “There are no critics in this country to comment on the Lapidus phenomenon with the intellectual firmness and lack of condescension with which Roland Barthes, for instance, dealt with Billy Graham and burlesque,” she complains.(2) Her text is a beginning, at least. In the same year, she explored the relationship between rock music and sexuality as embodied by Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix. Artists whose shows she reviewed include now-canonized names such as Richard Tuttle, Richard Artschwager, Willem de Kooning, and Ray Johnson, as well as—at least today—lesser-known ones such as Raphael Soyer, Paul Waldman, or the modernist John Marin, who had been set up as an American counterbalance the dominance of French artists. To Josephson, however, this seems too much of a burden for the poor man: “a bit like asking a butterfly to pull a battleship.”

Josephson herself certainly wasn’t struggling when it came to language: her criticism is full of equally humorous and striking images. Her essay on Andy Warhol, whose appearance and practice she calls mediumistic, is a brilliant piece of writing: “He is an example, I think, of the artist as perfect medium—both in the spiritualist and artistic sense. A medium, like a mirror, is defined by what it reflects, what is put into it, or done with it. But it remains itself essentially unchanged, though inhabited by this translucent and infinite sense of potential.” Female artists are, unfortunately, missing on her list. They were, as O’Doherty would later argue, hardly present in the New York scene of those days, a fact that Josephson took without complaint.

Protected by her anonymity, Josephson wasn’t shy when it came to criticizing her own trade and peers. In her review of de Kooning and Soyer (January/February 1973) she analyzes what she calls “network criticism”: “That’s what critical obtuseness is all about, not lack of insight into the work at hand, but into the subtler political effects of one’s stances.” The, if you like, collateral damage of such an approach is the worthwhile but standalone artist who is therefore being ignored. Her contemplations on Soyer, an outsider to New York’s art scene, are as a much a reflection of his work as of her role as critic: “In a situation where my praise and blame wouldn’t threaten anyone by proxy, I felt quite abandoned.” Her review of Johnson, reproduced here, is full of similarly savvy observations of the then New York art scene’s “how-to.”

In the April 1988 issue of Artforum, Josephson published “The History of X,” a kind of meta-narrative on history and identity, complete with false biographical details. All of these texts are gathered in the recent publication A Mental Masquerade. Josephson put down her pen when she was casually outed by O’Doherty himself some 20 years ago. She’s still hanging around somewhere, though, ready to return to her desk should necessity call her.

(1) Brian O’Doherty quoted in Astrid Mania, “A Mental Masquerade,” in Brian O’Doherty, A Mental Masquerade: When Brian O’Doherty was a female art critic: Mary Josephson’s collected writings, eds. Astrid Mania and Thomas Fischer (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2019), 13.

(2) All quotes from Brian O’Doherty, A Mental Masquerade: When Brian O’Doherty was a female art critic: Mary Josephson’s collected writings, eds. Astrid Mania and Thomas Fischer (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2019).

—Astrid Mania

Mary Josephson, “Ray Johnson at Betty Parsons”

Formalism’s art-from-art DNA linkages are still, despite bandwagon anti formalists, a beautiful historical model. But I was always aware of a fallacy in the system that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Some bright kids, who can’t find their way across the street alone, do well on tests because their talent is for taking tests. Formalism is a kind of art-historical test and you have to be bright in a dumb sort of way to read it “right”; it perpetuates itself exactly the way you’d expect, through a kind of historical narcissism. The artists in the class are good at taking the Formalist Projection Test, too. In such ways does history get a high from its own processes.

What gets neglected are those ahistoric or casual incidents without any theoretical armature to hang themselves on. Usually they belong to the overcrowded Dada ghetto, where the residents are dying to get out into the formalist suburbs. One way out is to piggyback not on art history but on the art scene—its rumors, gossip, oral traditions. Not that this is preparatory to an apologia for pickling trivia and putting them on MOMA’s shelf. It’s prompted by Ray Johnson’s show, “A History of the Betty Parsons Gallery,” at, of course, Betty Parsons.

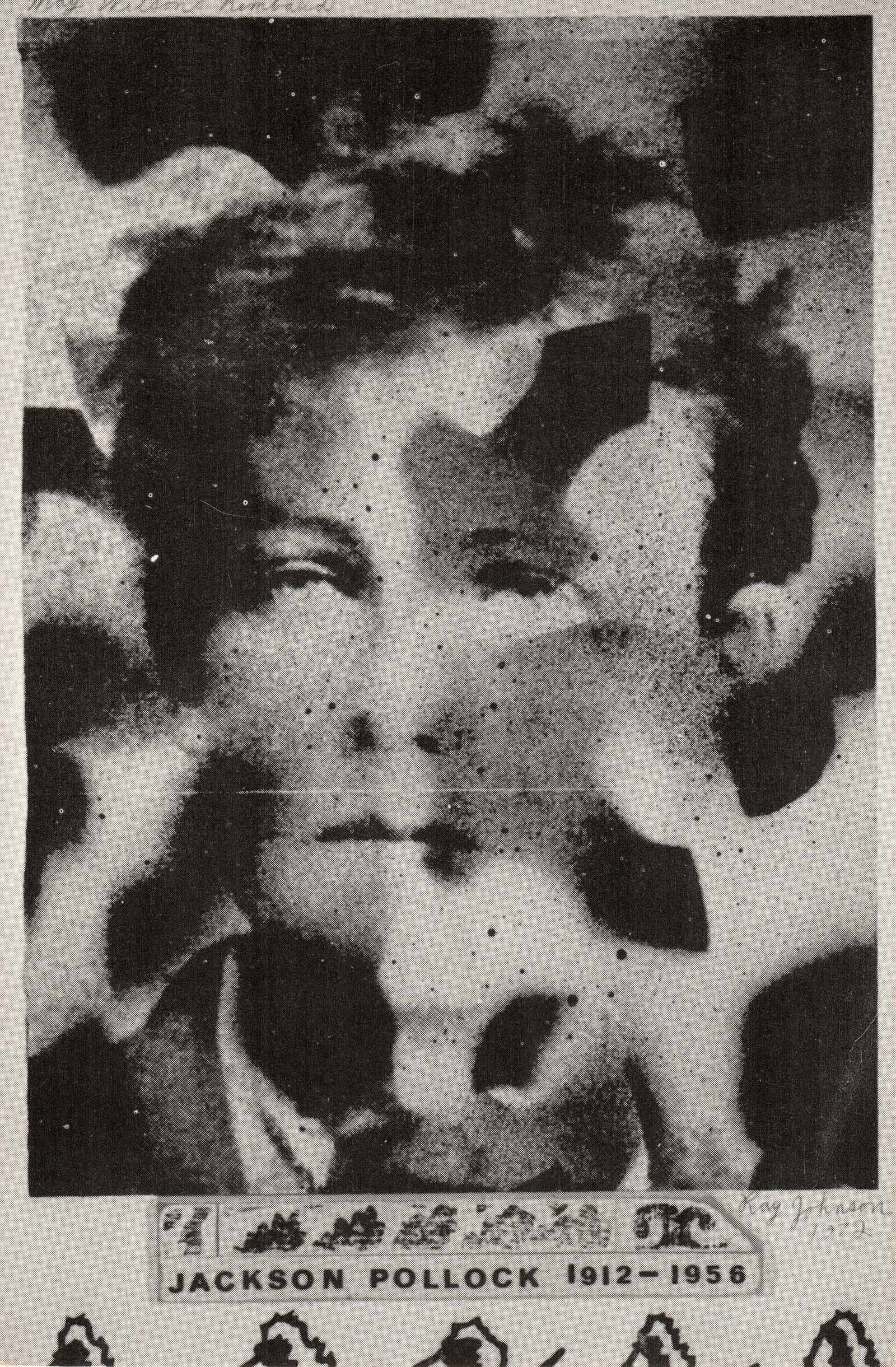

Making art out of the New York scene has been Johnson’s tireless occupation for Dada knows how long, and his “New York Correspondence School” keeps the mailman fairly busy. I understand he even has meetings, or at least announces them, and the invited guests are usually a neat political cut though the artist-critic-dealer-collector Big Apple. I don’t know if anybody ever goes; I suppose the announcements, often witty and sly, serve as anterior documentation, so that it doesn’t really matter if the meetings take place or not. If they did, they would merely be a New York opening without a show, that is, a place for gossip, which is, after all, Johnson’s medium.

I suspect all this may be a bit more valuable than we usually think, not just because of Johnson’s activities as attendant at the art-zoo, but because he may have a place in the unwritten history of neo-Dada, the only part of the New York scene to keep its pipelines to Europe open. Maybe more came through that pipeline than we know about, and maybe Johnson’s Kleenex version of history is trying to tell us something we don’t want to hear. He seems to be pretty smart about putting together the necessary survival kit for weathering New York’s smoggy esthetic atmosphere: he has the visual gifts (he clearly can make “serious” art if he wants to—the historical/genealogical shadow boxes at Parsons were all impeccable, if a little repetitive), the pre-pop deadpan, and a way of making the trivial almost serious in a town that often seems devoted to the opposite. He also has a keen estimation of the specific gravity of vanitas, and it’s a consummation of a sort to do the history of the Betty Parsons Gallery in the Betty Parsons Gallery. But he’s the one New York artist who can, like a dope pusher, move with impunity among freaks devoted to coke, hash (color-field), speed (kinetic), skag (Greenbergian esthetic—once you’re hooked, it’s hell on withdrawal). He’s gotten a show on a gimmick and then delivered.

The mail art people are pretty trivial, but triviality doesn’t mean they’re not fun or talented. It just means they have happy, post-comic-strip minds, a fatigue with high seriousness, and don’t feel like dressing their art in antiseptic clothing for uptown, or dirtying it up a bit for SoHo. Johnson disarmingly admits, as they do, that his art is at best minor, but his subject may not be. It’s a bit like a still-life painter who manages to tell us more about history than a big history painter. Very good minor work makes a lot of serious work look a little strained—which may mean no more than that minor work is informal and most major work is formal and vulnerable. Our best minor artists, however—and I use this here in the nonpejorative way one refers to good minor poets—are thus our best critics. Johnson exercises humor rather than wit, wryness rather than epigram; he collects New York artists like stamps, that is, without irony. In other words, he likes his subject matter, and could no more function outside the New York scene, to which he inescapably belongs, than Cézanne could do without apples.

“Ray Johnson at Betty Parsons” was first published in Art in America vol. 61, no. 3 (May/June 1973): 104–5, and later reprinted in A Mental Masquerade: When Brian O’Doherty was a female art critic: Mary Josephson’s collected writings, eds. Astrid Mania and Thomas Fischer (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2019, 53-55). The text is reprinted with the kind permission of Art in America, Brian O’Doherty, and Spector Books.