The world is burning. This is not a metaphor. The sky is bleached a searing lime green, tinged with burned orange that reflects off relentless choppy waves. Suddenly, the sky goes blood red and the horizon blackens, the sun a dull hole punched in the sky. Our view shifts, panning quickly to the left, then back again, as if searching for something, anything. The sky then changes again to a blinding sherbet yellow. The screen depicting this scene, mounted on a metal rack above a whirring circuit board, gives us a certain vision of our current reality. The shifting colors are a translation of information from a small atmospheric monitor mounted on the back of the rack. It’s not clear what directly causes the hues to brighten or waves to get that bit higher or more intense in Yuri Pattison’s sun[set] provisioning (2019) at mother’s tankstation—whether the car exhaust from the street outside, or the hungover breath from bodies in the room might make the scene that bit more trippy. The contraption offers a heavily mediated fiction, but it also makes an actuality visible and present: a drowned world, made hallucinatory and beautiful by toxins that saturate the air and water.

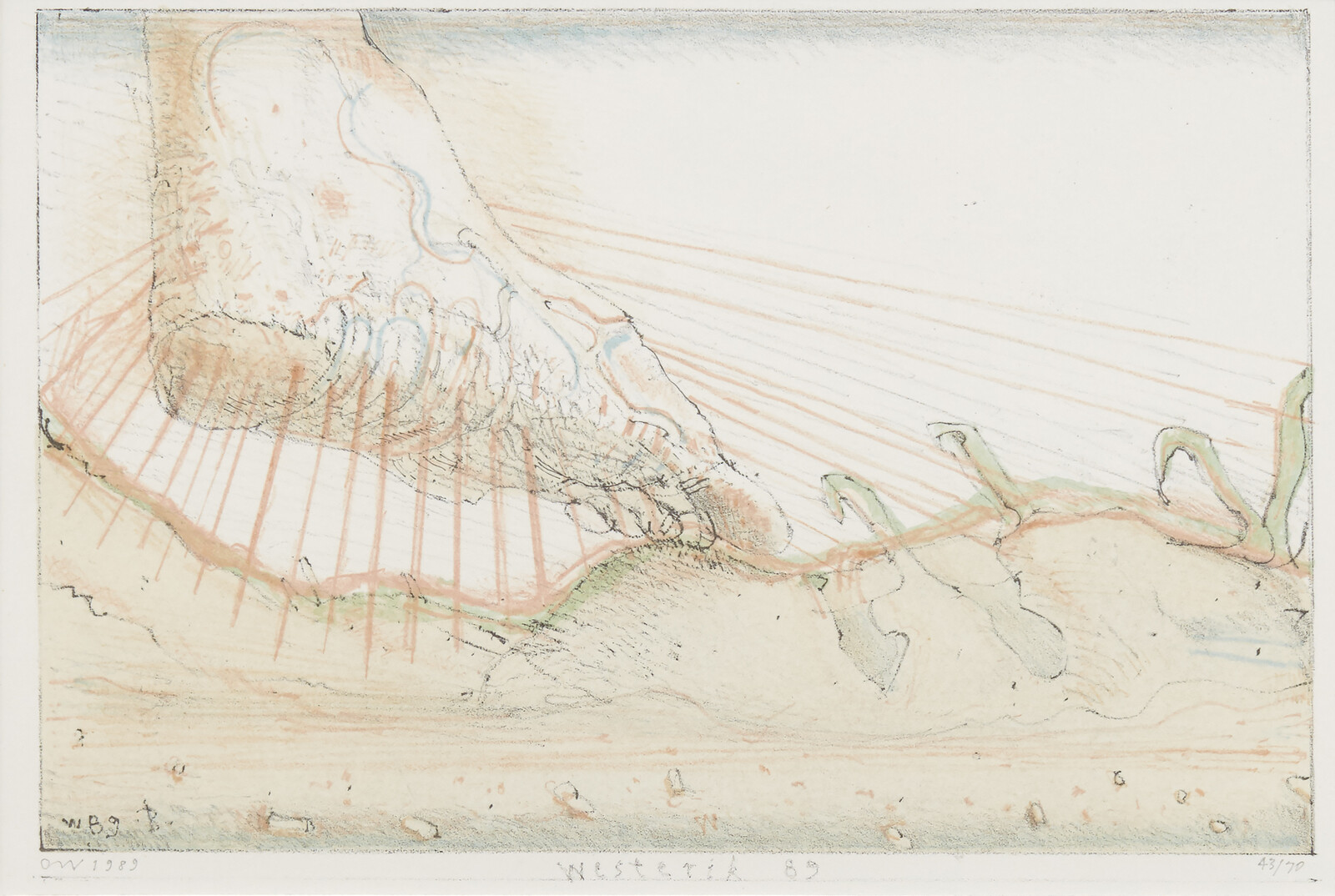

In moments of concentrated, entangled turmoil—events that feel too numerous and pointless to list or give name to yet again—art embodies the act of grappling with questions of agency and efficacy. How do we talk about things, what can we do about them? Above ground, in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, Kara Walker faces matters more directly, her massive fountain Fons Americanus (2019), adorned with figures from the colonial age and the transatlantic slave trade as a reminder of what England’s ongoing empire nostalgia rests on, told in its own language of hyperbole and monumental pomp. But it’s a short video in the basement hallway of her exhibition “From Black and White to Living Color” at Sprüth Magers, curated by writer Hilton Als, that feels more apt. The barely half-minute of Bad Blues (2011) is just Walker slouched on a dimly-lit couch with an acoustic guitar, staring dead-eyed at the camera to sing a standard blues song: “I got the blu…”—it cuts her off, jumping between multiple tries and re-starts, at one point layering the sound to make a ghostly, brief harmony. There’s no exultation of sadness, there’s no release; just a cluster of frustrated fragments. This is the language that feels appropriate to articulate the present, like another spectral fragment tucked in the corner of “body and landscape,” a posthumous exhibition of Dutch painter Co Westerik (1924–2018) at Sadie Coles HQ. The show’s set of paintings all seem to carry a sense of illness and unease with the human body, but it is the small print Luchtspiegeling [Mirage] (1989) that hits most directly: a wrinkled, white foot, looming over a hilly landscape. Deep veins trail river-like down the ankle, while pale orange rays radiate out from the limb like a perverse sun. It’s eerie, with the warm sense of celebrating something doomed, and it’s hard to not just take it at face value, as an old, white foot hovering over the land, about to push down, oblivious to whatever’s beneath it.

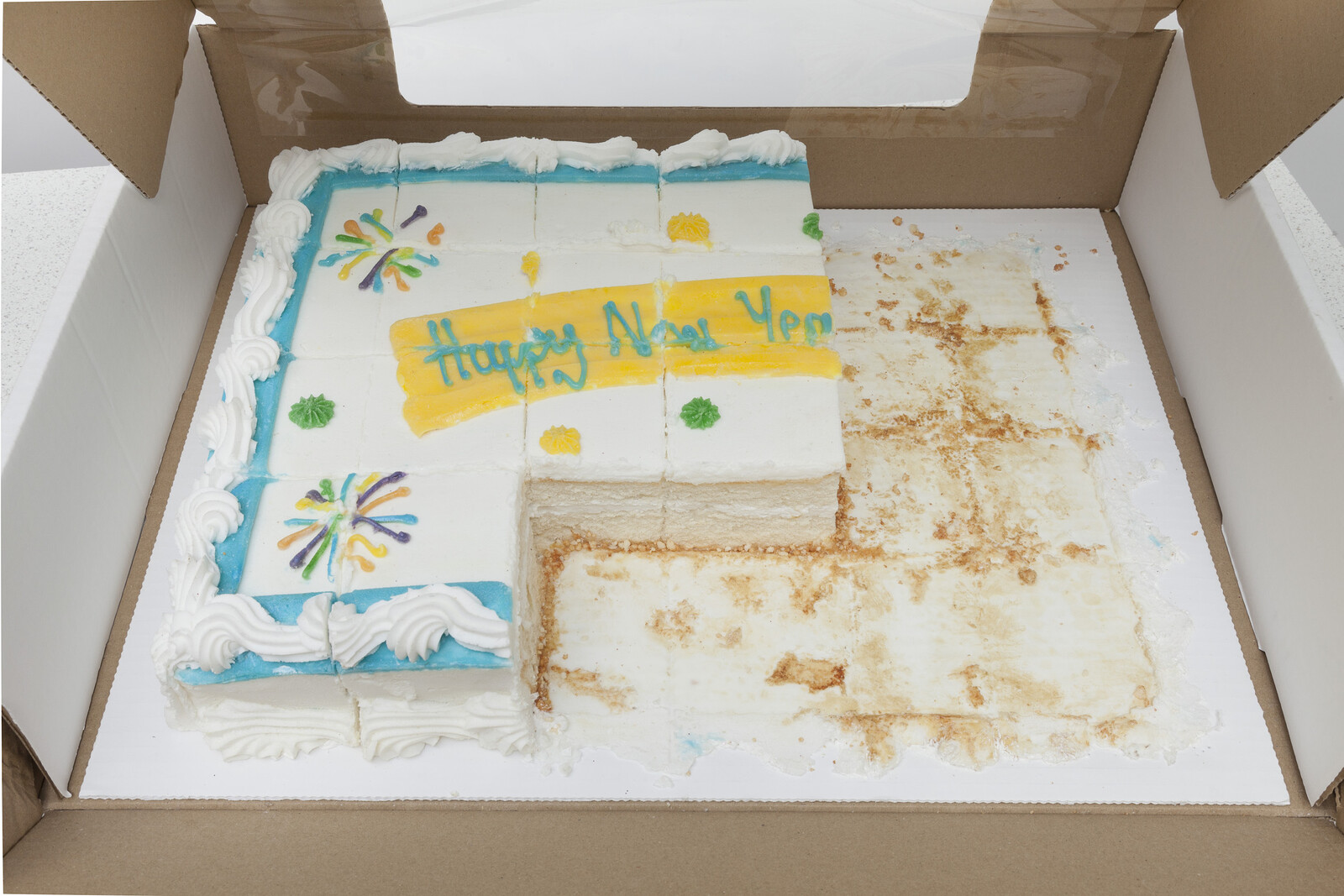

The other left foot, as it were, was in the Frieze London fair: a slightly different version of the same Westerik print at Sadie Coles’s stand, the sky in this version a steady, serene blue. There were some intrusions of life into the business and blue-sky affectations of the fair, like the shuddering street corners and sharply present portraits found in the solo booth of Ming Smith’s photography at Jenkins Johnson Gallery from San Francisco in Frieze Masters, or Cian Dayrit’s cloth banners at 1335Mabini from Makati in the Philippines in Frieze London, with archival colonial-era staged portraits embroidered over with slogans like “Pacify, Preach, Colonize.” At London’s Carlos / Ishikawa, an excerpt of a bland white kitchen counter sits in the middle of the floor, with a fairly lifelike plastic model of a half-eaten cake sitting on top, its icing spelling out “Happy New Yea.” Steve Bishop’s Thank You (2019) feels like an appropriate misplaced celebration here, the cake being one of those generic, over-sugary confections that fuel awkward office parties. On the other side of the fair at Cologne gallery Drei’s stand, Megan Rooney’s Renter’s Paradise (2019) is a trio of characters who seem to populate the same uneasy realm, temporary street bollards that have been dolled up with mops, burlap sacks, and Brillo-pad eyes. These don’t feel like satire so much as a clear mirror to their surroundings, sitting here in the waiting room at the end of the world.

Back in the supposedly real world, a circular blade is going full belt. Danh Vo’s exhibition “Cathedral Block Prayer Stage Gun Stock” at Marian Goodman Gallery includes a storehouse of tree stumps and stacks of wood downstairs, whereas upstairs there is a workshop turning the wood into various pieces of furniture and art. The wood is from a Californian walnut farm owned by the son of the former US Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, one of the main instigators of America’s increased involvement in Vietnam, where Vo was born. The open-ended process involves using the dark, knotted wood to make replicas of various twentieth-century chair designs, or to make whatever a purchaser might want from this wood touched by the wand of narrative. Though the show also unintentionally reflects other artistic and political realities. “Can you ask them to stop upstairs?” a gallery attendant asks the front desk as I walk in. “It gets a bit too much sometimes.” We are, we must remember, in a representation of a working workshop, the story of the wood being the actual work. Some of the wood makes an appearance in Vo’s concurrent exhibition, “untitled,” at the South London Gallery, providing wall paneling and forming the bases of several low, cushioned seats that dot the main gallery. “Untitled” gathers paintings, photographs, and a few sculptures by various friends, family, and collaborators that coalesce into an intricate and at times touching group show. It’s more telling, however, of the state of our public art institutions that it’s the institution that holds a slick, reserved exhibition of discrete artworks, while the commercial gallery presents a more messy, ongoing experiment, that at least poses a few more questions, not least: What kind of story do we want to invest ourselves in?

At an art school further down the road, a steel-girder lined room flickers with strobe-like intensity. The ten looping videos that make up Tony Cokes’s exhibition “If UR Reading This It’s 2 Late: Vol 1” at Goldsmiths CCA are a set of lectures animated by music, with appropriated texts touching on Aretha Franklin (The Queen is Dead: Fragment 2, 2019), Morrissey’s right-wing turn (in The Morrissey Problem, 2019, adapting a Guardian article by Joshua Surtees, titled “As a black teenager, I loved Morrissey. But heaven knows I’m miserable now”), and the use of music as a torture method. Mikrohaus, or the black Atlantic? (2006–08), although depicted in only black, white, and gray, manages to feel more personal, tracing some of the racial implications of minimal techno, quoting Paul Gilroy and members of Basic Channel over a half-hour mix of some of the music mentioned. At one point it features a quote from Édouard Glissant: “for us music, gesture, dance are forms of communication, just as important as the gift of speech (or writing).” Despite all its cerebral churning, Cokes makes this point best wordlessly in the video’s first few minutes, bombarding us with a frenetic and joyful burst of driving beats and flashing lights that feels like a temporary release and an instruction. How do we engage, communicate, grapple with a burning world? We should dance. Fiercely, ecstatically, and with intent.

%20provisioning_hr.jpg,1600)

%20Tate%20(Matt%20Greenwood).jpg,1600)