“Everyone has the right to a nationality,” states article 15 of the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” (1948) and “no one shall be deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.” As part of “Self-Determination: A Global Perspective,” Banu Çennetoğlu has filled the Irish Museum of Modern Art’s East Wing Gallery with three gigantic bouquets of gold helium letter balloons. Each bouquet, a mass of oversized jumbled letters, spells out a different article from the declaration. Throughout the course of the exhibition the balloons that make up right? (2022–ongoing) will deflate, lowering to the ground, until nothing remains but their empty carcasses.

An initiative of Annie Fletcher, IMMA’s director since 2019, “Self-Determination” explores the establishment of new post-World War I nation-states—including Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Ukraine, Turkey, Egypt, and Ireland itself—focusing on the role that art and artists played in statecraft and the formation of the national imagination. The site of the exhibition, the Royal Hospital Kilmainham (built in 1684 as a home for retired British soldiers), holds significance in the construction of the Irish nation. It was considered as a potential headquarters for Oíreachtas Shaorstát Éireann, the newly established government of the Irish Free State in 1922. Included in the exhibition is a set of architectural drawings, borrowed from Ireland’s National Archives, detailing the unrealized plans for the building’s conversion.

Occupying much of the former hospital’s vast interior, the exhibition takes as its starting point calls in 1919 for the rights of oppressed small nations to “self-determine” made by US President Woodrow Wilson at the Paris Peace Talks and, from Gloucester prison, by Sinn Féin founder Arthur Griffith. These are hefty historical reference points and, with over 200 artworks and as many archival documents, “Self-Determination” is one of the largest and most ambitious exhibitions ever mounted at IMMA. Its subject matter is reflective of Fletcher’s wider aspiration to transform the museum into a “shared civic space” where urgent political issues facing the Irish public can be thought through and debated together in community. The exhibition, which is being unveiled in three stages, is the culmination of three years of research funded by the Irish government’s Decade of Centenaries program to mark the nation’s independence.

The epic historical, geographic, and political scope of “Self-Determination” is both commendable and sometimes frustrating. It defies, in an often exhilarating manner, any tendency for Irish centenary projects to be either inward-looking or self-congratulatory, presenting a complex and appropriately messy view of Ireland’s national emergence within a global context. But missing a printed floorplan or guide to its twenty thematic sections, it can also be bewildering and, with its multiple lengthy information panels, maps, and timelines, feel like a history lesson as much as an art exhibition.

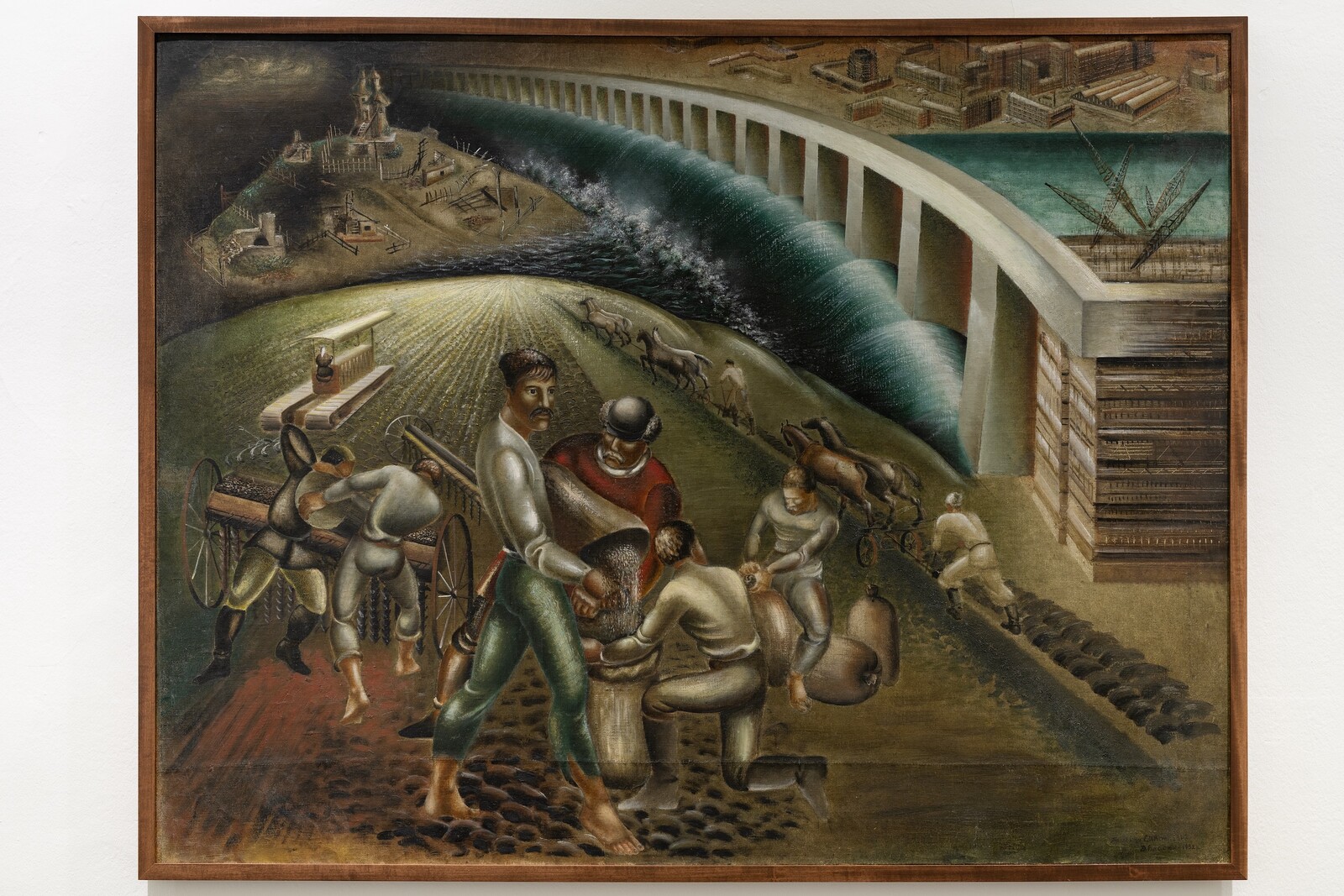

The show’s ambitions pay off in moments such as its detailed investigation of Ireland’s first hydroelectric power plant built in Ardnacrusha, County Clare, in co-operation with the German engineering firm Siemens-Schuckert. Officially opened in 1929, the Ardnacrusha plant was one of the largest and most advanced engineering feats of the period and served as a model for large-scale electrification projects worldwide. It’s depicted in Seán Keating’s 1928 heroic painting View of Dam from Power Station Side with Figures in the Background (1927–28) and in Declan Clarke’s film One Power For All The Land (2023), commissioned for the exhibition.

Keating’s painting hangs alongside other works portraying grand modernist projects, such as Ukrainian artist Dmytro Vlasiuk’s painting Dniprelstan (Dniproges Dam) (1932) and Polish artist Rafał Malczewski’s Building the Rożnów Dam (1938). Brought together under the theme “Extractive Industries,” these works generate a sense of how these initiatives functioned both as infrastructure and as national symbol—their power exists at the level of both energy and image. Vlasiuk’s painting also forms a link to our current moment of global unrest, provoking thoughts of the 2023 Russian detonation of the Kakhovka Dam on the Dnipro River in Ukraine and the devastation that ensued.

Commissioning new works that respond to the socio-political themes of the exhibition is also a significant part of the project. Many of these invited artists have addressed the marginalized communities, such as women and children, that were often excluded from visions of self-determination and sovereignty predicated on upholding the patriarchy. Finnish artist Minna Henriksson’s Limits of the State (2023) skillfully and sensitively maps out, in a wall-drawing and audio work, the shared struggles of both Irish and Finnish women for reproductive rights during the establishment of independent nation-states. This is one example of the exhibition exploring a more sinister side of nationalism, particularly in its convergence with organized religion. “Self-Determination” could have gone further down the darker paths that nationalism can and has followed, especially in light of the shocking anti-immigration riot that occurred in Dublin in November 2023 and the far-right protest outside Dáil Éireann in September.

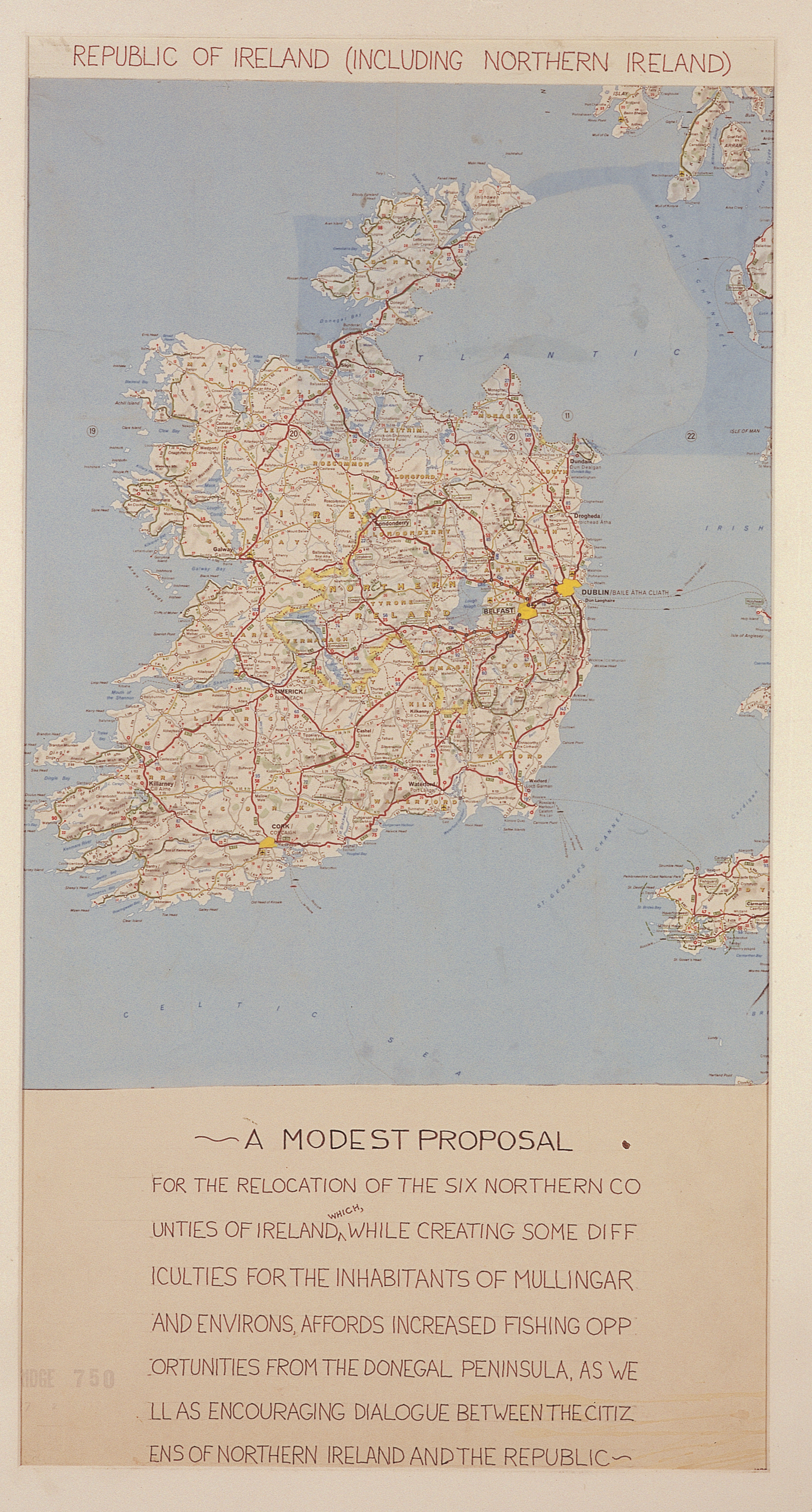

There are moments of humor or levity that punctuate the predominantly serious subject matter. Brian O’Doherty’s 1980 collage map work A Modest Proposal activates a Swiftian Irish tradition of satire as critical response to tragedy, suggesting as a solution to The Troubles “the relocation of the six Northern counties of Ireland,” superimposing them onto the center of the Republic and, admittedly, “creating some difficulties for the inhabitants of Mullingar and environs.” Not all attempts at satire sit comfortably within an otherwise sober and sincere exhibition. Several works have been commissioned from Belfast-based Array Collective, whose creative method involves “‘craic’ and collaboration as a means of resistance.”

Their work Regalia: The Slapper (2023) presents the viewer with a small castle-like structure built from children’s bright yellow Lego bricks, mounted on the wall at eye-level. According to the collective, the title refers to Bernadette Devlin McAliskey’s slapping of British Home Secretary Reginald Maudling after he claimed, falsely, that British soldiers “fired in self-defense” during Bloody Sunday, as well as the rubber gloves of domestic labor and hidden reproductive work of child rearing. This and other gestures, like the curatorial decision to place Irish artist Niamh McCann’s Stream of Consciousness (2022), a bronze copy of Michael Collins’s nose, in front of an image of the John Hughes statue of Queen Victoria that resided in the courtyard of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham for decades, feel overly flippant in the context of this exhibition.

It’s doubtful that Ireland has reached the comfortable point of being able to look back at its turbulent past with such detached humour. And current world conflicts have made clear that other nations and regions present in “Self-Determination” certainly have not. The Irish public sense a connection between their own historical struggles and current global injustices, demonstrating a commitment to engaging with these political events, from the Ukraine to Palestine. If Fletcher’s vision of transforming IMMA into a shared civic space is to be fully realized, then more of these discussions and actions must also enter the halls of Kilmainham.