January 31–February 4, 2018

To my left the casual love of mismatched hearts is expiring. The American woman says, “you’re sad,” and the Frenchman nods. She tells him to calm down. It is breathtakingly awkward. They resign themselves to stillness until a grinding electronic drone heralds their graceless end. She makes a break for the cash bar, and he, with less determination, joins the nearest crowd. He stares with them in solidarity at a webcam feed showing empty winter highways projected large, and finds solace.

This is transmediale, Berlin’s premier art/media/technology festival and sometimes boneyard for feckless romance. Over three decades it has showcased ideas by those working at the forefront of digital aesthetics and theory. Its mandate, by its own decree, “…aim(s) at fostering a critical understanding of contemporary culture and politics as saturated by media technologies.”

“Face value” is this year’s umbrella motif, and, like past themes, it is highly accommodating. Spanning five days, the lectures, exhibitions, conversations, and screenings investigate the power of surfaces, from the origins of “face value” as economics lingo to its application by racist ideologies within the mediasphere. With so many experiences to be had and shared here, both visitor and contributor are apt to become lost in the fray, as are the festival’s original intentions.

The group show “Territories of Complicity,” curated by Inga Seidler, garnered mixed responses for this very reason. Housed in dark cubicles, the exhibition “takes the free port as referential starting point to explore how covert systems, technological infrastructures, and zones of exception shape our economic, socio-political realities.”1 Some think it is complicit by name and nature for touting injustices anointed as art. For others, the installations touch upon diverse global crises in unexpected and profoundly instructional ways. Both assessments hold credence, but the strongest elements of “Territories” succeed in broadcasting a message difficult to ignore, and for that I must cast my vote in its favor.

Finding Fanon (2015-2017) by Larry Achiampong and David Blandy belongs especially to this latter category. The project’s title refers to three films that use the writings of Frantz Fanon as a departure for investigating how systemic racism complicates the artists’ friendship and shapes their respective lives. Part two is distinct for taking place entirely within the lambent world of Grand Theft Auto 5 (2013). Its protagonists are the artists rendered as avatars, treading through an empty Los Angeles. They stare at shipping container yards, into a tunnel, and out across nightwaves beneath a virtual moon. A woman’s voice speaks about heritage, fraternal bonds forged in game space, and future human cruelty. In time, the figures approach the edge of the continent, and the narrator invites us to contemplate absolute emancipation. Before fading away, she initiates a call to arms: “… only when restraint is exercised at the right moment, in the calm of night, then can power be exemplified. But when will we find peace? … Only the oppressor knows peace because he is rarely challenged.”

Challenging oppression is as much a mission for the speakers as for the artists. Right out of the gate, Nina Power rallies for beheading hegemonic leaders, inspiring an audience member to cheer.2 Alex Foti does something similar with a freestyle rap. However, enticing the crowd with protest energy is only a preliminary warm-up for the intense discussions about cyber warfare, fractal fascism, cryptocurrency, and the weaponization of language that follow.

The last of these categories is a panel discussion unto itself, during which the conjecture is made that all utterances participate in the perpetuation of oppression. Sybille Krämer demonstrates this idea, at least in part, by arguing that words perform two violences. The first being insult, the “brutal force” that marks someone as a target for abuse. The second being language utilized by administrative authority to malicious ends. The two work in tandem as a “janus-head” of power, superimposing a value system on humans via its self-authored hate rubric. Within the digital realm, Krämer claims, identities are represented by symbolic monikers and are therefore all the more susceptible to verbal reduction, discrimination, and control—conditions that could quickly manifest in the physical world with dire consequences.

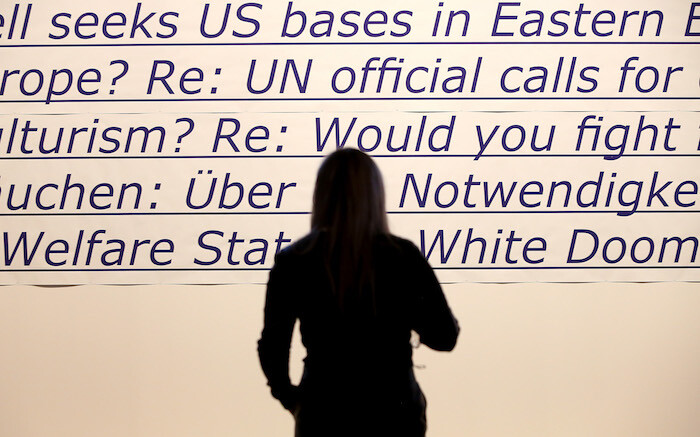

If one finds the underlying dangers of linguistics to be less than riveting, then it is only a matter of turning one’s attention to Nick Thurston’s Hate Library (2017) to fully appreciate the immediacy of Krämer’s concerns. According to the artist, the installation consists of five-and-a-half components, including twelve music stands arranged in a circle (referencing the EU flag); twelve comb-bound books containing exhaustive collections of hate speech; and three walls also mostly filled with hate speech. Engaging procedural contemporary poetics, Thurston culled his source material from the online chat rooms of extreme right-wing communities, and he did so with apparent ease and glut. The sheer quantity of text alone is chilling, and predictably the messages held within are appalling and dumb, but most disconcerting is its accessibility. If all of this vitriol is “just a few clicks away,” as the press release states, then the term far right is truly no longer an accurate description of distance.

Near to Hate Library is transmediale’s most visually arresting feature, Probably Chelsea (2017) by Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea E. Manning. Using genomic identity construction technology and DNA provided by Manning herself, Dewey-Hagborg produced thirty possible gene expression portraits of her collaborator. The result is collection of 3D-printed faces that span the scope of race or gender but are all, technically, Chelsea Manning.

Suspended from the ceiling on lines of monofilament, the portrait objects are hollow shells reminiscent of ancestral death masks. Their placid expressions and blind eyes contain a hint of Buddhist charm that turns eerie when hued with the oversaturated dyes that fail to replicate dermal luminosity. The portraits attain peak bizarreness from a posterior view because they look exactly the same only inverted, like a face that has been sucked into itself. For better or worse, they are Januses, too, and in light of Sybille Krämer’s language beast, we should consider ourselves lucky they cannot talk.

https://2018.transmediale.de/program/text/territories-of-complicity.

Moments later she tests out a similar bid for castration which is, shall we say, not as popular.