“Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship in the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick,” wrote Susan Sontag in Illness as Metaphor (1978), “although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.” This quote opens “Misbehaving Bodies” at the Wellcome Collection, which places Jo Spence’s healthcare work from the 1980s in conversation with Oreet Ashery’s 12-part web series “Revisiting Genesis” (2016). Through references to chronic and fatal illness, identity formation, medical discourse, and the politics of healthcare, the exhibition pays particular attention to how citizenship to the “kingdom of the sick” might productively disrupt and diversify common understandings of life and death, the…

A pair of bland, near-identical phrases printed on banners in front of London’s Wellcome Collection assert the similarity of the two artists featured in the current show: Oreet Ashery and Jo Spence, they respectively read, “explore illness and identity.” Head inside, however, and the design of “Misbehaving Bodies” emphasizes the two artists’ differences. Three of the five flat screens showing Oreet Ashery’s “Revisiting Genesis” (2016), a meandering, 12-episode video series about a fictional woman with a terminal illness, are displayed in booths hung with fabric dyed in shimmers of rose-pink, wine-red, and liver-purple. They bring to mind protective divisions in otherwise open spaces—the curtains pulled around beds in hospital wards, say, or the dens that children construct by draping bedsheets over furniture (complete, at…

“Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship in the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick,” wrote Susan Sontag in Illness as Metaphor (1978), “although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.” This quote opens “Misbehaving Bodies” at the Wellcome Collection, which places Jo Spence’s healthcare work from the 1980s in conversation with Oreet Ashery’s 12-part web series “Revisiting Genesis” (2016). Through references to chronic and fatal illness, identity formation, medical discourse, and the politics of healthcare, the exhibition pays particular attention to how citizenship to the “kingdom of the sick” might productively disrupt and diversify common understandings of life and death, the body, and community.

Spence’s autobiographical artwork Beyond the Family Album (1979) takes the conventional form of the family photo album—photographs and press clippings are affixed to large sheets of paper, accompanied by captions and extended passages of text—but subverts the form by manifesting as a counter-archive of the self. By charting her divorce, her parents’ ill health, and her own struggles with chronic asthma, in addition to interrogating the invisibility of women’s domestic labor and damaging representations of class, gender, and sexuality in the media, Spence sought to “represent the un-representable”.1 Her politicized and confrontational style was designed to be both pedagogic and emotive: formulating a new pictorial language that reclaimed control of the image of the female body. “Much of my [work] has been described as in ‘bad taste’, ‘unsuitable for galleries’, ‘revolting’, ‘ugly’, ‘narcissistic’ and ‘obsessive’: pejorative and dismissive words, presumably spoken because of thwarted expectations of the viewer/critic who might prefer to continue to consume the female body.”2 The series “Phototherapy” (1984-86), a collaboration between Spence and Rosy Martin, demonstrates how they adapted co-counseling techniques by performing and re-enacting traumatic memories through photographic narrative and montage in order to develop agency over their pictorial representation.

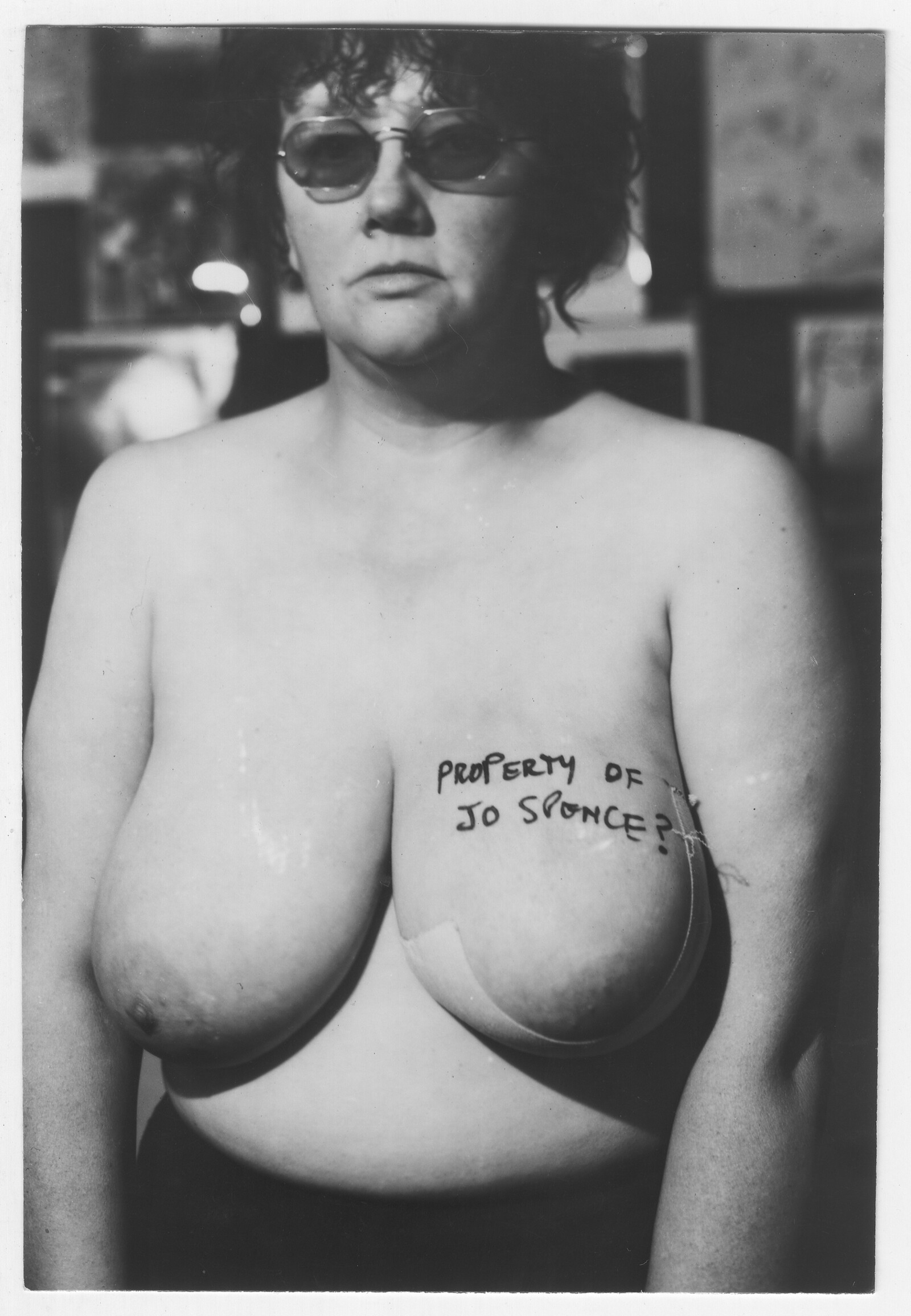

Influenced by Bertolt Brecht’s ideas on the importance of visual education, Spence often made work using materials that could be both accessible and disseminated widely. “This is a people poster,” reads a segment of Beyond the Family Album. In private, she produced scrapbooks, which incorporated writing, personal photographs, nutritional plans, and newspapers clippings. On one, the word “CANCER” is scrawled in black felt tip across a photograph of Prince Charles and Princess Diana. Another double spread asks, “How do I give up RESPONSIBILITIES without being ILL?” That question, among others, reverberates throughout both Cancer Shock (1982–84) and The Picture of Health? (1982–86), particularly in her 1982 self-portrait, in which “Property of Jo Spence?” is written across her bandaged breast. In the late 1980s, Spence used her experience of breast cancer as a nexus to explore the stigmatization and infantilization of the ill and aged, in addition to considering the difficulty of retaining psychic or physical autonomy within the space of healthcare. Spence saw individual bodies as nuanced sites of intersecting political conflicts. For example, the work particularly connects the objectifying medical gaze with the way women’s breasts were perpetually fetishized in popular advertising and pornography.

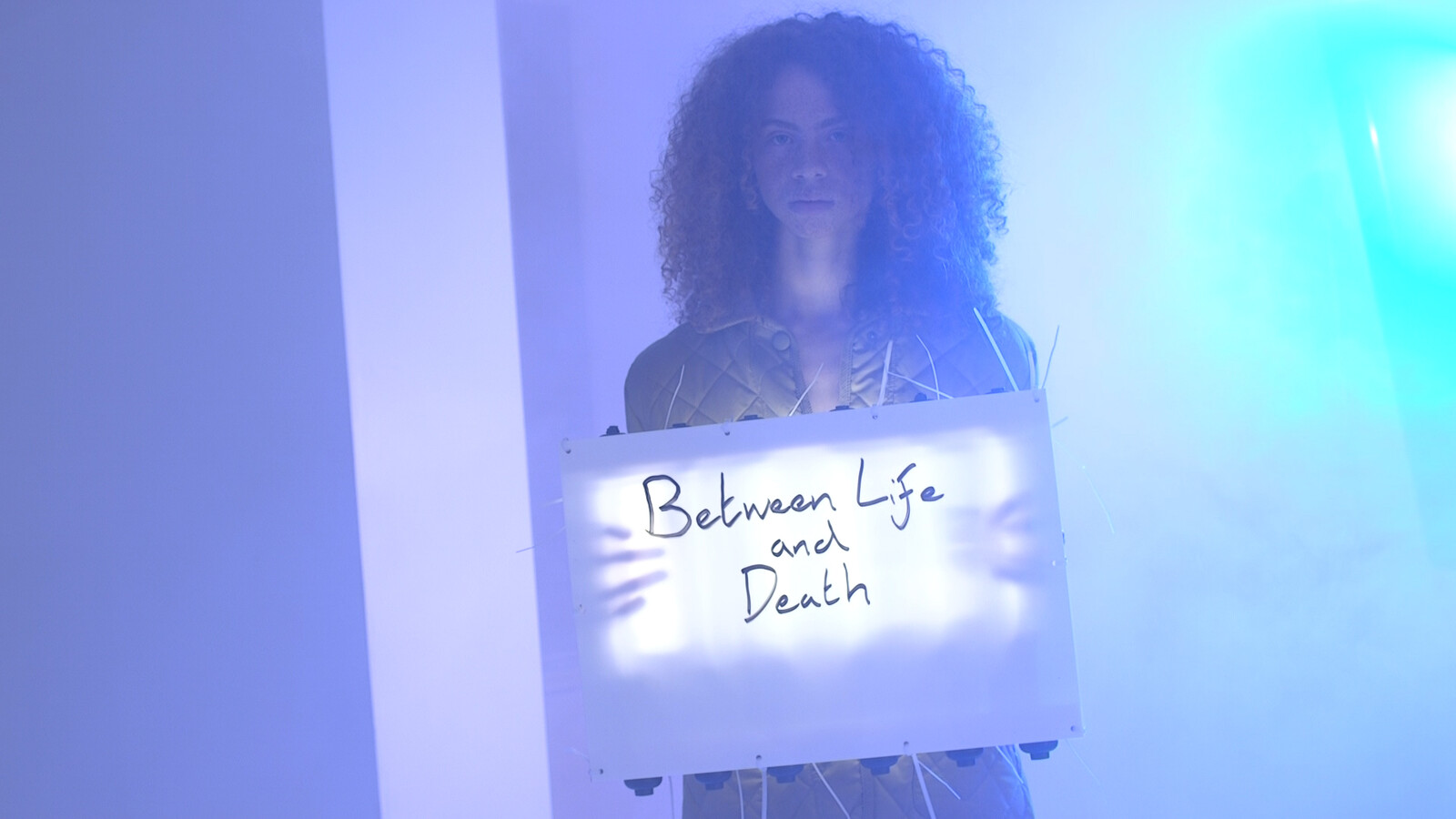

An activist, Spence intended for her personal experience to be a catalyst in enacting wider social change: she was invested in the liberation of women, the working class, and other marginalized communities. Similarly, in the roundtable discussion published in the exhibition’s accompanying booklet, Ashery talks about the interplay between the intimacy of both artworks and the institutional scale of the Wellcome: “this is where the politics are situated: between the private and personal themes and how a large audience will encounter this.”3 The multiple tent-like viewing environments in which episodes of “Revisiting Genesis” are screened have been carefully designed in order to be soft and comfortable for those with chronic illness or pain. Their tie-dye fabrics and the giant teddy bear shaped beanbags lean into the saccharine tendencies favored by establishments of care. The episodes intersperse the fictional story of Genesis—a dying artist and an allegory for the invisibility of female artists—with real-life experiences from individuals who live with life-limiting illness and conditions like cystic fibrosis, cancer, and Crohn’s disease. The narrative questions the role of death in the contemporary digital era: the effect of social media on grieving, breaches of privacy, and emergent technologies, such as AR gravestones. The gaze of social media—the body as statistics, an algorithm, data to be harvested—is analogous to the medical or patriarchal gaze interrogated by Spence.

Akin to Spence’s work, “Revisiting Genesis” is intersectional, anti-capitalist, and feminist. Personal mourning is connected to cultural and historical loss, reflecting on the erosion of the welfare state in tandem with Ashery’s own memories as a precarious, young migrant worker. “Death is an exaggerated form of life, so that if you are poor and you become ill you will become poorer. The economy of marginality people experience over their lives becomes highlighted in death.”4 Ashery’s words bring to mind Johanna Hedva’s text “Sick Woman Theory” (2016): “An insistence that most modes of political protest are internalized, lived, embodied, suffering, and no doubt invisible […] that the body and mind are sensitive and reactive to regimes of oppression—particularly our current regime of neoliberal, white-supremacist, imperial-capitalist, cis-hetero-patriarchy […] that it is the world itself that is making and keeping us sick.”5

Jo Spence, Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography, ed. Frances Borzello (London: Camden Press, 1986), 98.

Jo Spence, Cultural Sniping (London: Routledge, 1995), 198.

Oreet Ashery, “A roundtable discussion between the artists Oreet Ashery and Martin O’Brien with the academic Patrizia Di Bello and curator George Vasey,” in Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery, Wellcome Collection, exhibition booklet, 2019.

Oreet Ashery, “A roundtable discussion between the artists Oreet Ashery and Martin O’Brien with the academic Patrizia Di Bello and curator George Vasey,” in Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery, Wellcome Collection, exhibition booklet, 2019.

Johanna Hedva, “Sick Woman Theory,” Mask Magazine (January 2016), http://www.maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory.

A pair of bland, near-identical phrases printed on banners in front of London’s Wellcome Collection assert the similarity of the two artists featured in the current show: Oreet Ashery and Jo Spence, they respectively read, “explore illness and identity.” Head inside, however, and the design of “Misbehaving Bodies” emphasizes the two artists’ differences. Three of the five flat screens showing Oreet Ashery’s “Revisiting Genesis” (2016), a meandering, 12-episode video series about a fictional woman with a terminal illness, are displayed in booths hung with fabric dyed in shimmers of rose-pink, wine-red, and liver-purple. They bring to mind protective divisions in otherwise open spaces—the curtains pulled around beds in hospital wards, say, or the dens that children construct by draping bedsheets over furniture (complete, at the Wellcome, with giant pink teddy bears sporting creepily long, snake-like arms). Spence’s works are more soberly displayed. Hung on freestanding white walls, her photographic self-portraits and laminated collages are supplemented by explanatory texts and audio commentaries by other artists. So far, so museum. But the standard wall paint is complicated by a note in one of the scrapbooks that date from her breast cancer diagnosis in 1982 until her death from leukemia ten years later, displayed in a vitrine: “Everything is stripped from you in that white, clean Hell.”

Spence was referring to the cancer ward, with its spotless walls and bleached floors, its doctors in white coats and surgeons in white masks. The Picture of Health? (1982–86), a photo montage comprising dozens of laminated collages made with Terry Dennett, Rosy Martin, and Maggie Murray, is the largest of her works on display. Covering four years of her life, and two large walls, it echoes the diaristic, improvised feel of her scrapbooks: staged self-portraits pasted onto colored card alongside newspaper clippings, polemical texts, and photographs taken in the hospital. Spence’s confusion, terror, and fury are palpable, but so are her defiance and humor. In one panel, she describes an occasion when, without introducing himself or asking permission, a young male doctor drew an X on the skin above her left breast, and told her he was going to remove it. She was 48, but the experience made her feel as powerless as a child. In “Phototherapy,” a cycle of self-portraits made in collaboration with Martin between 1984 and ’86, Spence dresses as a snarling baby, a toddler, and an angry child: a punkish parody of the infantilizing effects of her treatment.

Spence’s photo montages can be didactic, but that was part of the point. She wanted them to perform a social function: to educate, inform, and perhaps even heal. Illness imposed a system of power relations—between the healthy and the sick, doctors and patients—that Spence reconfigured through her work. “In the shadow of my fears,” she wrote in a text panel in Cancer Shock (1982–84), another photo montage shown opposite The Picture of Health?, “came a kind of rebellion.” “Property of Jo Spence?” she wrote on her breast—the same spot the doctor had marked—in a black-and-white photo taken just prior to surgery (The Picture of Health: Property of Jo Spence?, made with Dennett in 1982). She refused a mastectomy and had a lumpectomy instead, the results of she documented in several photographs on display. A fragment of text in The Picture of Health? meanwhile reads like an invocation of renewal in the face of a death sentence: “I begin to see beneath the surface of the image. I can now begin the work of re-inventing myselves.”

Rather than her rebellion, it’s Spence’s collaborative instinct that is echoed in Ashery’s work. The episodes of “Revisiting Genesis,” which feature shifting casts of non-professional actors, feel like dreams set in heavenly waiting rooms. Nurses and patients gather in bright, pale spaces to talk about death and the digital afterlife, while shimmery visual effects, hand-held camerawork, and digital animations contribute to the dissociative mood. The pervading sense is of agreeable disintegration: the physical collapsing into the digital, living becoming dying, documentary melting into fantasy, yet none of these processes (in contrast to Spence’s experiences) generate much in the way of trauma. As such, “Misbehaving Bodies” never quite succeeds in making the case for the pairing of these, beyond the obvious thematic parallels and desire to foster a sense of intergenerational dialogue (Spence was born in 1943, Ashery in ’66). This is partly thanks to the inexplicable decision to brand the respective halves of the exhibition with their names. The vitrine housing Spence’s notebooks is mounted on a white plinth that yells “JO SPENCE” in chunky, monumental letters, while a curly “Oreet” is hung from the ceiling on a gold chain, like an oversized necklace. The result is a frustrating show that encourages viewers to investigate these artists’ work further—anywhere other than the institution.

Jo Spence, Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography, ed. Frances Borzello (London: Camden Press, 1986), 98.

Jo Spence, Cultural Sniping (London: Routledge, 1995), 198.

Oreet Ashery, “A roundtable discussion between the artists Oreet Ashery and Martin O’Brien with the academic Patrizia Di Bello and curator George Vasey,” in Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery, Wellcome Collection, exhibition booklet, 2019.

Oreet Ashery, “A roundtable discussion between the artists Oreet Ashery and Martin O’Brien with the academic Patrizia Di Bello and curator George Vasey,” in Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery, Wellcome Collection, exhibition booklet, 2019.

Johanna Hedva, “Sick Woman Theory,” Mask Magazine (January 2016), http://www.maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)