The Minimalism nurtured in SoHo and Marfa produced industrial cubes, steel beams, and gleaming planes until it was fortified and impenetrable, refracting metaphor or intimacy. Exposing rather than building up, its economical materiality favored the truly elemental, ruling out the human, or even the organic, as frill. So what to make, literally, of a substance like gold—an element weighed equal parts malleable and stable, mythical luxury, electrical conduit, and vitamin? The average human bloodstream contains a fraction of a milligrams of it; it is the treatment for both rheumatoid arthritis and dental cavities.

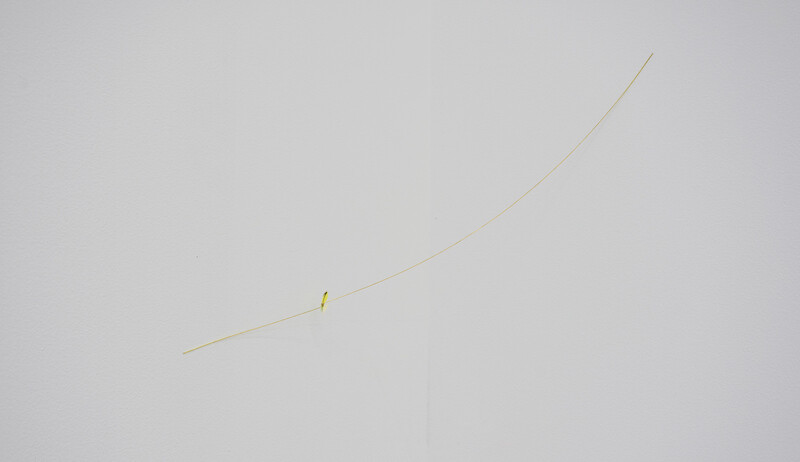

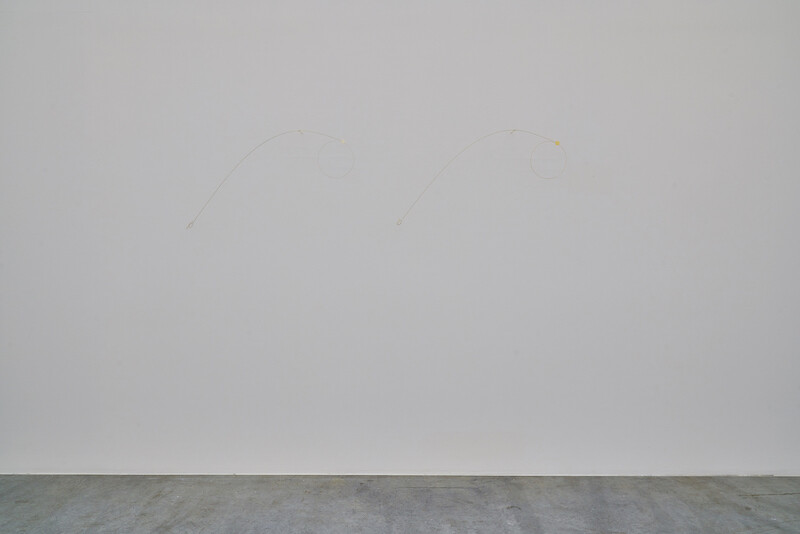

Joana Escoval’s fine, elegant gold wires embody Minimalism’s essentialism but not its burdens. She makes lines. This exhibition is an arrangement of soft, flat sculptures in pleasing shapes hanging on walls that share the movement’s austerity: the components of Escoval’s sculptures take up room in the way of Fred Sandback’s yarns delineate negative space, but refuse to occupy their volumes; they echo the gilded repetition of Walter de Maria’s Broken Kilometer (1979) while sidestepping its mass. Installed, her sculptures are aware of but don’t draw attention to each other, a whisper network over a choir ensemble. Lithe, skinny forms like An empty list of things missing (all works 2018), slackly parallel to an ensnared stray vine, and Our land was a forest, catching a single electric-lemon and obsidian parakeet feather, both resemble a seam that has come loose from its environment, rather than interrupt it. Pinned to points over the full height and width of the gallery space, the few spare works on view are assembled so modestly and quietly that they highlight their own displacement, scattered around the antiseptic stage of a couple of white cubes, many of the works positioned far enough from each other and so thread-thin that it’s entirely possible to miss one at a glance. Every work on view could be pressed into and hidden in a closed hand.

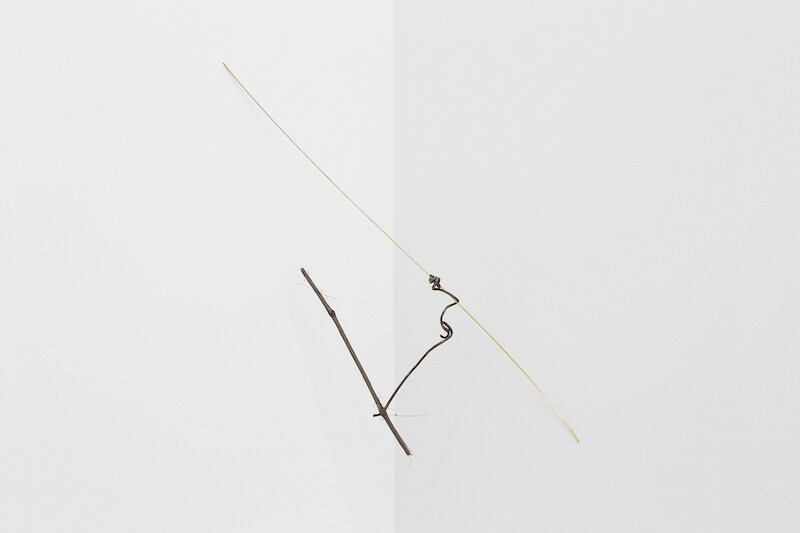

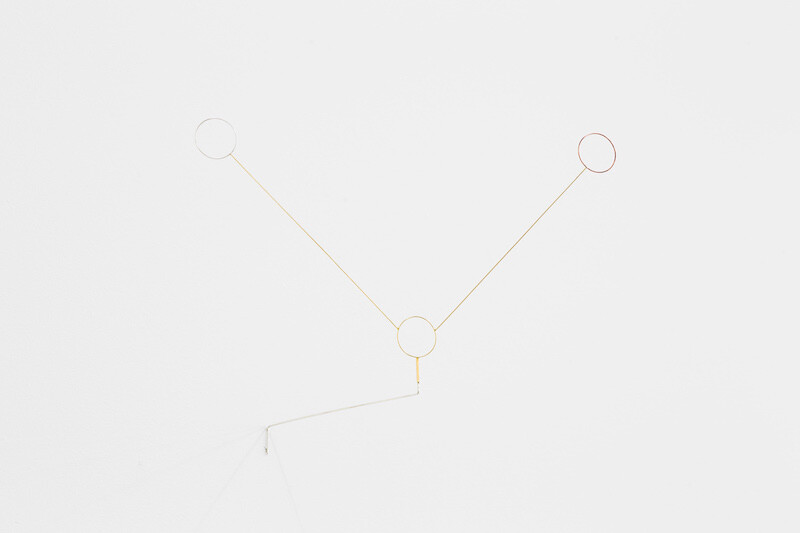

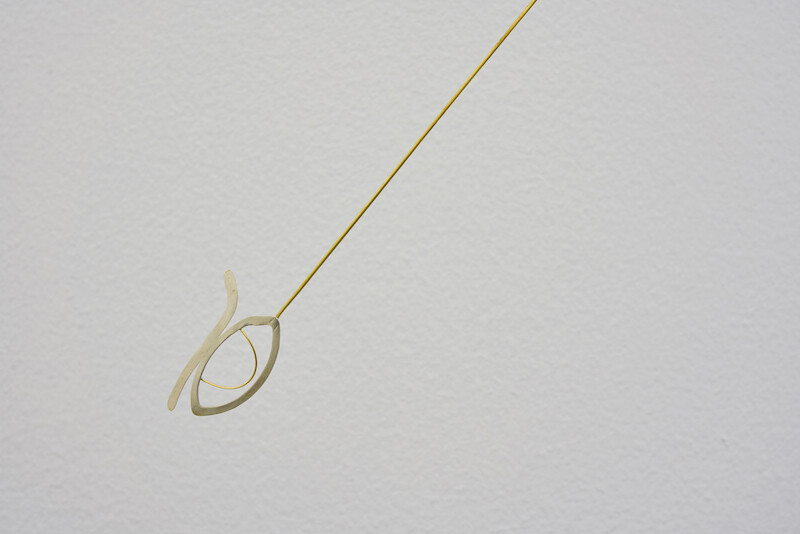

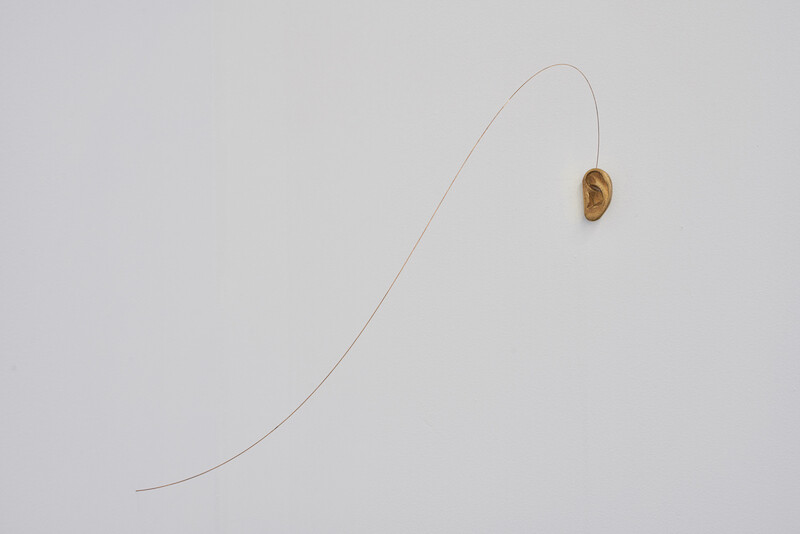

Melting and coaxing copper, silver, brass, and bronze, these contours—such as the circles and lines of Time flows ever on and the pair of heavy-lidded, gazing eyes tacked much higher up into the wall in Dia [Day] and Noite [Night]—undergo subtle transformations out in the open: shape-shifters in captivity. The same goes for It arises not from any cause, but from the cooperation of many, an isolated, startlingly lifelike human ear dipping from a gentle curve. The conducive metals also form an anthropomorphic bridge from material to animation in The sun lovers I, a fist-sized creature dragging a tail several times its length while climbing up the wall, though it only makes it a few inches off the ground.

Hanging from a single, centered golden nail very high up, hovering just below the ceiling fold, two intertwined hoops the size of dinner plates form something of an infinity symbol in Healthy forests provides clean water provides healthy forests. Repetition of the work’s deadpan, cyclical title announces both diagnosis and solution to one of our most urgent environmental crises. Healthy forests is typically installed outdoors, the brass sculpture eventually rusting from humidity and rain, refreshed by the very message written in its vulnerable matter.

Weathering brass is a process of refining as much as it is ravage; decoration will not add to, but obliquely replace, what is already there. Minimalism’s reluctant commander, Donald Judd, sharpened a characteristically brusque manner of writing; he set aside the least number of words for the work he was closest to. On frequent subject Kenneth Noland, he devoted most of his column inches to laboriously describing Noland’s “Circles” series, comparing their ultramarine, cerulean, and light blue concentric hues before ending the review with a typically compressed, yet satiated, “This does a lot.”1 The slight, shimmering strokes of Escoval’s smooth sculptures, intervening into nothing but occasionally themselves, lifeless but giving life, are equations, legends, an SOS. Each millimeter-thick line continues itself until it has reached its natural lifespan, and maybe falls away; some maintain their cyclic existence, loops without hinges. Concrete and galvanized iron are commandments, menace, thunder, relics, authority; these are pencil tracings on paper already caught in the tide. Still—they do a lot.

Donald Judd, Complete Writings 1959–1975 (New York and Marfa, Texas: Judd Foundation, 1975; reprinted 2005 and 2015), 57.