Naeem Mohaiemen’s new film, which lends its title to this solo exhibition of his work at the Bildmuseet in Umeå, opens with an image of a beautiful young woman. Sufiya, played by Kheya Chattopadhyay, is standing with her eyes closed, her head caught between two old-fashioned surgery lights covered in dust. In Listening to Images (2017), Tina Campt follows Fred Moten in asking “what is the sound that precedes the image?”; the question comes unbidden into my mind as a landline telephone begins to ring softly but insistently off screen, forcing the woman to open her eyes and return to the surface of the world.1 As the film cuts to a slow panning shot of the crumbling façade of the abandoned Lohia Hospital in Kolkota—formerly a maternity hospital—I wonder what this woman heard in the privacy of her own mind before she faced the ruinous present.

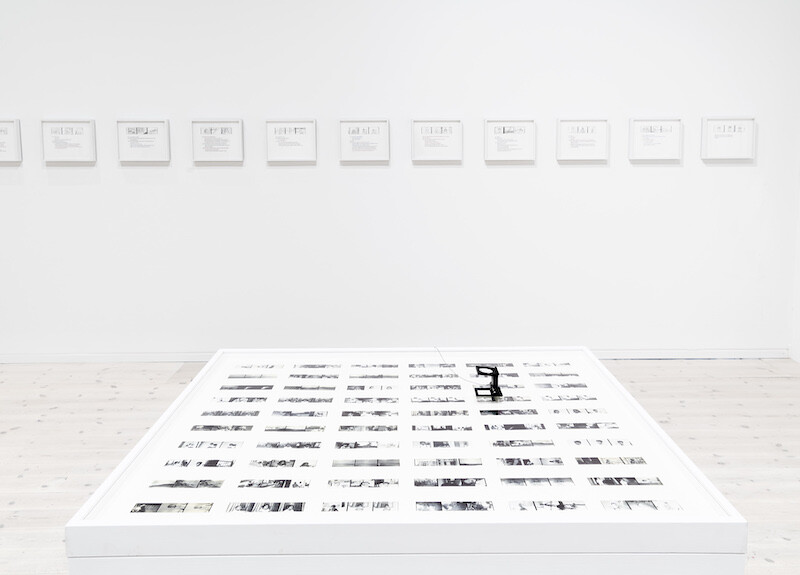

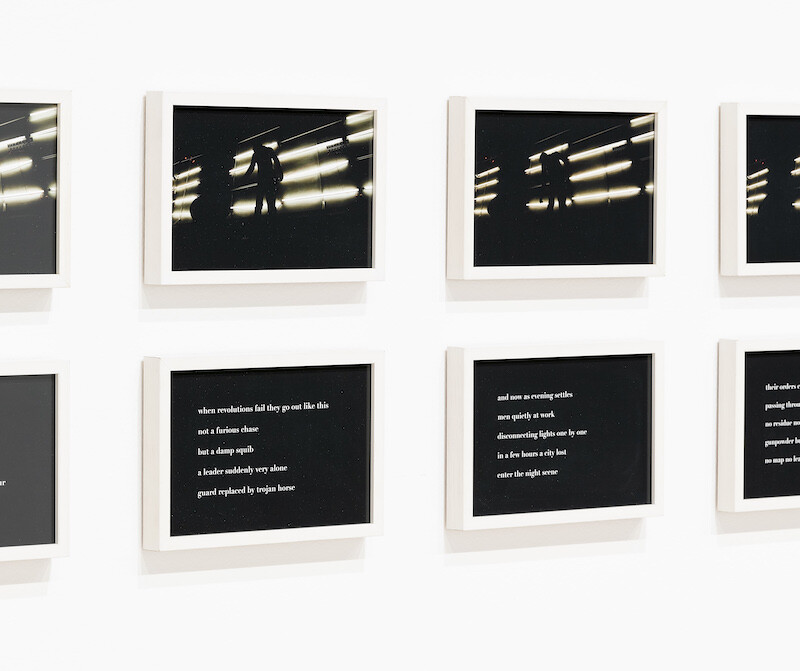

According to the exhibition guide, Mohaiemen’s work is “a counter-history of minor events” that destabilize grand historical narratives using imaginative annotation, slow panning shots, and speculative documentary strategies. I think that both the exhibition and the film are more profoundly about the frequency at which loss becomes audible, sensible. For example, the installation of altered photographs and a short video, Ranklin Street, 1953 (2013), nominally focuses on a box of photographic negatives the artist’s father took with his first camera of close relatives in their family home in Old Dhaka. A more recent work, Baksho Rohoshyo (Chobi Tumi Kar?) (2019), takes the same box of negatives as a point of departure for an installation of drawings that “slow the photograph down as a form of simulacra and projection,” according to Mohaiemen.2 Each work pictures fragments of a family history that has been scattered across the world in the wake of Bangladesh’s independence in 1971. Yet the lingering meaning produced by both projects matches the overwhelming effect of Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown) (2020), which is not historical deconstruction but mourning for a time before the disaster which is still unfolding.

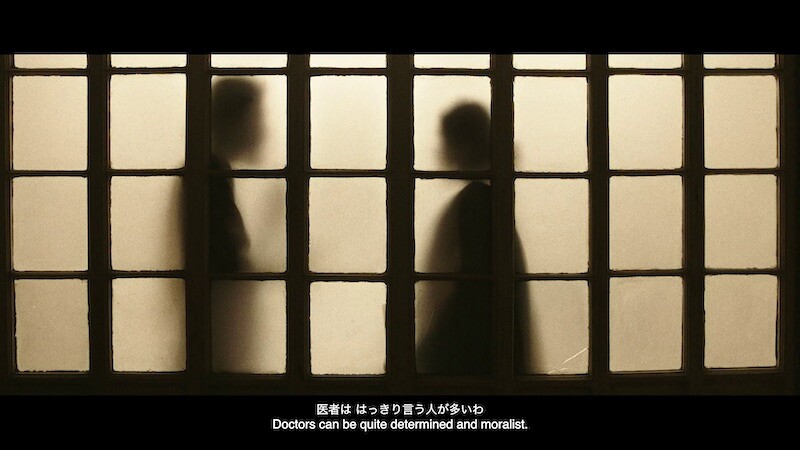

The film is gorgeously shot. Its pace is measured to match the texture of time spent waiting, its sepia-toned lighting producing an aesthetics of suspension that recall classic film noir, like Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place (1950) or Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (1947). About 20 minutes into the hour-long film, one scene breaks with the work’s pervasive nostalgia. Sufiya and her husband, Jyoti, played by Sagnik Mukherjee, are seated amid a maze of discarded hospital furniture that could be from the film noir era. Jyoti asks Sufiya if she brought the water bottle. He can’t remember. She looks around from her seated position, apparently dazed, then spots it nearby on an adjacent stack of bedframes. She hands him a modern-looking aluminum thermos, he drinks, and they sit in silence for a moment as the camera pans out to capture a wider view of the evidence of abandonment that surrounds the couple.

She taps his shoulder, wordlessly reclaiming the thermos cap, and then asks him a question: “I wonder… did the communists obey the caste system with water?” Her husband replies: “In public space? Are you insane?” amused at her apparent lapse in rational political thinking. “So, caste-ist only at home?” she retorts, smiling at his amusement but unwilling to let go of the topic, her brow furrowed earnestly. He responds more seriously: “That depends on many things. Which side of the border?”

The exchange is lightly sarcastic but politically significant. An informed viewer would know that Jyoti is a Hindu Bengali from East Bengal while his wife Sufiya is a Muslim Bengali from West Bengal. Mohaiemen’s portrait of their marriage inverts a common demographic perception that also served as a justification for the Partition of Bengal in 1947, which assigned Muslims and Hindu populations to Pakistan and India based on where each demographic was declared to be in the majority. The woman’s reply is a phrase that sounds like a rhyme: “This side, that side. All sides collapse.” In Bengali—which I do not speak—it has the cadence of an aphorism. With that phrase the spell is broken, history is withdrawn from the frame, and the viewer is returned to suspension in an endless present.

“The disaster is related to forgetfulness,” Maurice Blanchot reminds us, “—forgetfulness without memory, the motionless retreat of what has not been treated—the immemorial, perhaps.”3 Blanchot is describing the impossible limitlessness of the disaster. It saturates both internal and external experience, capable even of severing the relation between one moment and the next inside a person’s mind. This side, that side. All sides collapse. “I will not say that the disaster is absolute; on the contrary, it disorients the absolute. It comes and goes, errant disarray,” Blanchot qualifies, “an irresistible or unforeseen resolve which would come to us from beyond the confines of decision.”4 Both the disarray of lives and the memory of those lives that Mohaiemen renders in the exhibition’s photographic installations are pictured again with exquisite precision in the banal exchange between husband and wife. The underlying personal disaster—Sufiya’s decision to refuse end-of-life medical treatment—becomes entangled with other disasters, at different scales, in the characters’ past and in the viewers’ present. Loss metastasizes.

No diagnosis is given, no illness illustrated in Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown). The only reprieve from suspension is the woman’s presumed death at the end of the film—and that reprieve is hers alone. Jole Dobe Na is the title of a Bengali folk song: “Those who die in love never drown.” I want to believe this.

Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 6.

Email to the author July 7, 2021.

Maurice Blanchot, The Writing of Disaster (Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 3.

Ibid., 5