The second time I visit Hiwa K’s retrospective at Dubai’s Jameel Arts Centre it’s still daylight. In the outside sculpture park is the wood, cement, and metal sculpture One Room Apartment (2008-17), shown at Documenta 14 in Athens. A single staircase leads to a worn mattress on a morbid metal bed without walls. I climb it to take in the scene from above, and watch a bird land on the bedframe. Several kids are sprawled on a grassy patch, and in the distance is Palazzo Versace’s promise of decadence. In a city of labor camps and high-rises, Hiwa K’s comment on the rise of single-person living near minefields in Iraqi Kurdistan, the home he fled from and has recently returned to, takes on a different meaning. Where economic deprivation is fueled more by free-market economics than war, his work on atomized dwelling points to the divergent ways in which art manifests in different contexts: from the refugee crisis in Athens to the ongoing controversy over migrant workers’ conditions in Dubai.

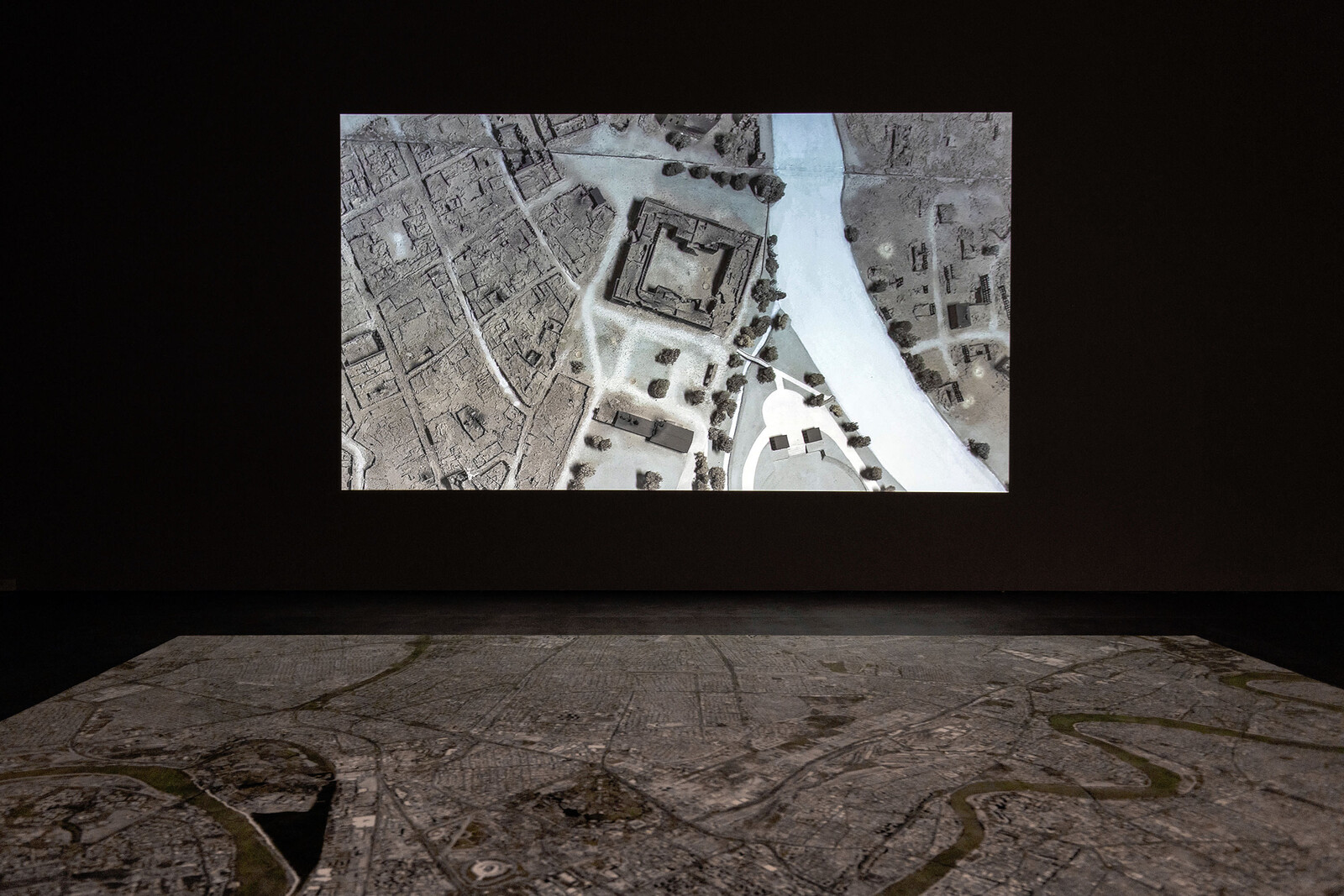

Around the unsheltered bed, Hassan Khan’s multi-channel sound installation Composition for a Public Park (2013) expounds, fittingly, in three languages on the nature of bondage. Inside the exhibition, Hiwa K’s video installation View from Above (2017), a panorama of post-World War II Kassel, is reflected on the wall, mirroring a room-sized carpet printed with an aerial view of Baghdad. One part of a new commission entitled Destruction in Common (2020), the work’s title is taken from a statement made by the Iraqi-Kurdish narrator, M, in View from Above—“all cities have destruction in common”—as he seeks asylum in Europe. It references the UN’s division of postwar Iraq into safe and unsafe zones, and calls attention to the arbitrariness of these designations.

M’s recollections of his home conflict with the city of J, the “unsafe” place from which he must claim to be fleeing for refuge, and the map of which he memorizes in order to pass his asylum interview. Memory rubs against cartography, and from clever oppositions—a safe zone in an unsafe country, geographies that are forgotten, two characters in counterpoint—emerges the idea that fiction leads to freedom. The audio component of Destruction in Common—a meditation by Yogi Shunyamurti, founder of an ashram in Costa Rica, describing the release from the “narrative principle” as true liberation—forms a counternarrative. Here, the mind is posited as a storytelling machine that needs to free itself from the script and, correspondingly, the ego, while View from Above seems to suggest that political emancipation can only arise with a scripted modus operandi. As the video reaches its climax, it becomes unclear whether the two characters, the narrator and M, are not in fact one and the same protagonist.

Hiwa K’s practice interrogates the boundaries between the real and the mapped, exploring a range of migratory forms and creating transnational linkages through maps, music, and social sculpture. Taking the form of a rehearsal for a flamenco dance that never happens, Moon Calendar (2007) enacts another absence. The performance was filmed at the “security building” turned Iraqi National Museum of War Crimes, a place of detention and torture under the Ba’athist regime. Measuring his heartbeat through a stethoscope, the artist attempts, and fails, to match the movement of his heels to his heart. It’s a symbolic testament to the violence inflicted on other bodies, reimagining horrors beyond our cognitive understanding. Yet the situatedness on which his work depends risks being lost as the work moves between different cities (this show will travel to Dublin and Toronto). Across contexts, the work shifts, effecting its own displacement across time and place, and deepening tensions between individual biography and collective fictions. An ornate bell cast from discarded rockets, bombs, bullets, and mines in Iraq—The Bell Project (2007-15), which references church bells melted to form cannons, and which sounds out a single note—is less powerful here than at the Venice Arsenale for which it was originally commissioned, where it linked to a 700-year-old Italian foundry.

Music is also central to This Lemon Tastes of Apple (2011), in which Hiwa K and his collaborator play Ennio Morricone’s score to Once Upon the Time in the West (1968) amidst an escalating anti-government protest in Sulaymaniyah. The title references Saddam Hussein’s 1988 chemical attack on the Kurds (the poison gas was said to smell like apple) and the lemons carried by protestors to lessen the effects of teargas. Taste and music carry us across time, as past and present intermingle. In a 2018 documentary for PBS, Hiwa K suggested that Kurdish identity is “about being formless.”1 That shattered form is expressed in the motorcycle mirrors mounted onto a pole that the artist balances on his nose in Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) (2017), refracting his journey as a refugee from Sulaymaniyah through Athens and Rome in the 1990s. The shapes of words burn through pages in Do you remember what you are burning? (2021), shot in Saray Azadi, the same square as This Lemon Tastes of Apple (2011), where the artist solicited students to aim magnifying glasses on books in the sunlight as an act of dissent. Where language fails, he seems to be saying, performance becomes a mode of excavating these absences and migrations. As a narrator in View from Above states: “In order for you to be accepted as a refugee we will need to give vision to your hand, and to give you a voice that can reach as far as the eye.”