Walking through this survey of American art in the age of anger and anxiety, I kept returning to the curatorial statement’s seemingly innocuous proposal that new technologies are “complicating our understanding of what is real.” Are our horizons now so narrow, it occurred to me, that an algorithm’s ability to generate a derivative image is really more consciousness-expanding than such longstanding preoccupations of art as spiritual experience or the natural world? Or might the title’s appeal to something “better” serve to distract us from the already complicated and unarguably real events playing out beyond the walls of the museum, with which this biennial can seem reluctant to engage?

A generation of artists are, on the show’s evidence, retreating from a hostile public sphere into their own carefully cultivated worlds. This tendency manifests both in the valorization of marginalized identities through the adaptation of folk traditions to the present—notably ektor garcia’s use of crochet to articulate a nomadic cross-border experience—and in the tendency towards opacity, most explicitly in the panels of smoked black glass suspended precariously over the audience’s heads by Charisse Pearlina Weston (of [a] tomorrow: lighter than air, stronger than whiskey, cheaper than dust, 2022). Many of the realities gathered here are more-or-less private, mediated through (and guaranteed) by the body—as in Jes Fan’s 3D-printed scans of his own limbs—or fully accessible only to the initiated members of a community.

It is easy to sympathize with the impulse to erect boundaries against the gathering forces of far-right reaction, as evinced by works such as Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio’s reflection on the historical deportation of migrant workers (Paloma Blanca Deja Volar/White Dove Let Us Fly, 2024). By the same measure, the willingness of a major institution to platform minority subject positions should not be taken for granted, and curators Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli with Min Sun Jeon and Beatriz Cifuentes should especially be credited for giving pride of place to work that challenges the rising tide of transphobia (including Seba Calfuqueo’s transcendent TRAY TRAY KO, 2022, which helps to illustrate that the construct of gender as in any meaningful sense “real” is much more recent and localized than its advocates would like to believe) and protests the repeal of women’s rights (notably in the textiles of Harmony Hammond).

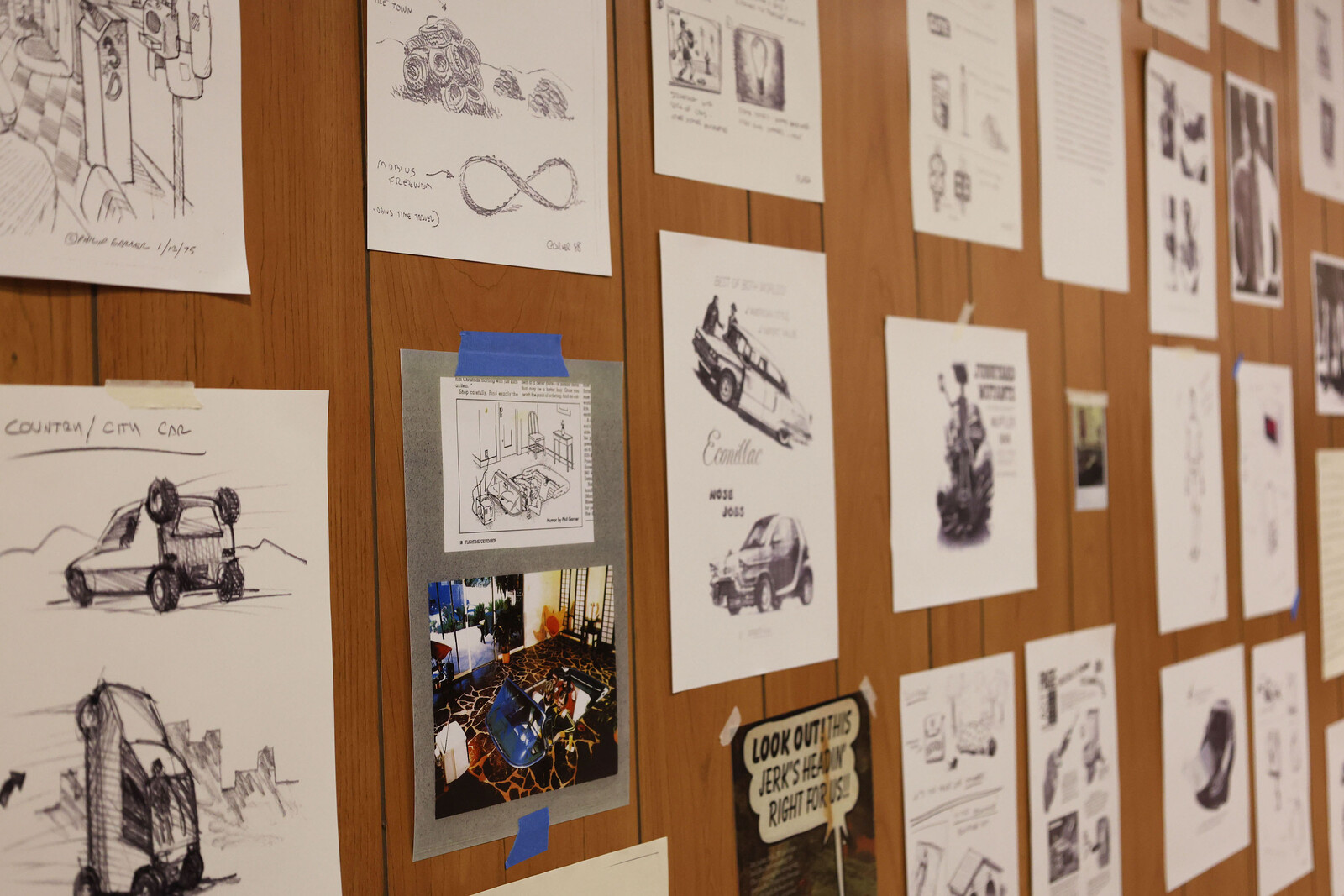

Yet the most memorable contributions move beyond the entrenchment of existing positions. Pippa Garner’s absurdist drawings—in which the symbols of consumerist American culture are used to subvert their own ideological function—offer a salient example of how the language of hegemony can be turned against itself. Installed in its own room on the sixth floor, Nikita Gale’s self-playing piano (TEMPO RUBATO (STOLEN TIME), 2023–24) might at first seem to be a literal illustration of the familiar theme of the artist’s withdrawal from the public arena for their own protection, or another work of academic art calibrated by lawyers to test the boundaries of what constitutes individual authorship. But the piano’s strings have been removed, and so the melody is transformed by the hammers’ thump into an insistent rhythm that—elevated by the installation’s exceptional sound and lighting design—suggests a world set in motion by a maker for whom invisibility might be a revolutionary strategy rather than a way out.

Similarly, Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich’s beautifully executed film installation about Suzanne Césaire—Too Bright to See (Part I) (2022)—does more than rescue an unjustly neglected historical figure from obscurity. By filtering its investigation into memory through Césaire’s own romantic and Surrealist aesthetic, the work proposes a much more radical model for the measure of an individual’s influence than the prominence of their name in the historical record. As Gale’s installation puts forward that one might need to remain hidden to act freely, so Too Bright to See demonstrates that the individuals who do most to effect change are not necessarily those who are most eager to be seen doing so.

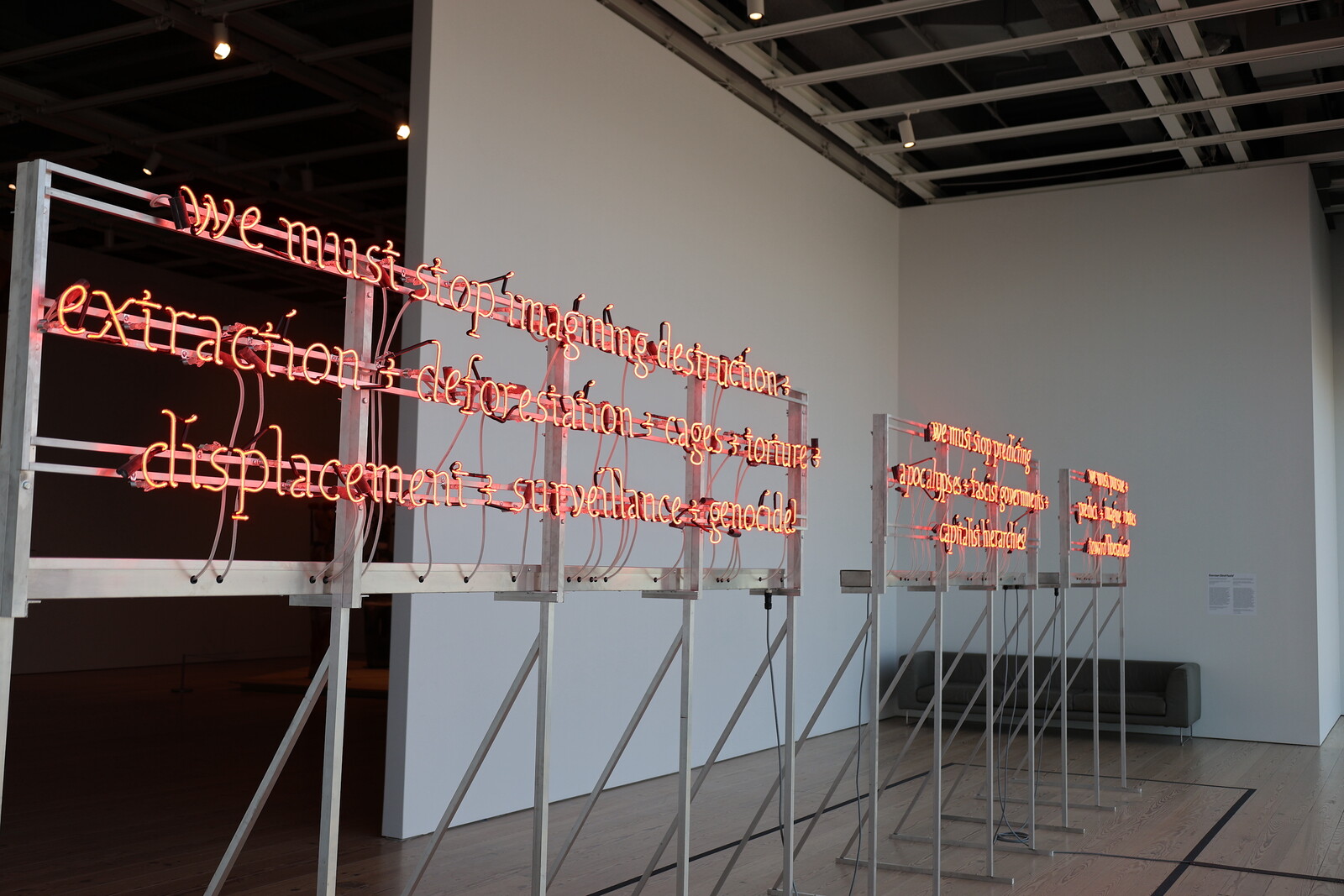

To read Césaire’s essays is to be struck by her conviction that her chosen medium—the French language—can through the application of techniques from Surrealism to sincerity be transformed from a tool of colonial oppression into an instrument of liberation: it opens up new possibilities for the real rather than fixing its limits. A similar principle underpins the neon text work by Demian DinéYazhi’ that shines out through the fifth-floor window like an illuminated sign. As well as offering a timely reminder that hope is a more effective catalyst for revolution than despair, the pointedly titled we must stop imaging apocalypse/genocide + we must imagine liberation (2024) offered a welcome example of the capacity of art to alert audiences to realities beyond the museum by surreptitiously flashing the phrase “free Palestine” across the Hudson.

That this message had effectively to be smuggled into the show—the curators claim to have been ignorant of it—is indicative of the anxiety surrounding even the blandest criticism of Israel’s increasingly indefensible prosecution of its war on Gaza. For all the diversity of the voices it gathers together, the curators’ proposal for a model American society is conspicuously averse to the friction between perspectives on which a functioning democracy depends. Indeed, the feeling lingers that while the positions staked out by so many of these works might be controversial in the wider society, they are unlikely to upset either the visitors to—or the backers of—metropolitan institutions of contemporary art. The intervention by DinéYazhi’ sneaks an uncomfortable truth into this otherwise safe space.

There are more conventional attempts to work against the sense of many different worlds having been collected together without being encouraged to interact. Sharon Hayes’s Ricerche: four (2024) arranges a semi-circle of deckchairs around a multi-screen video installation in which LGBTQIA elders reflect on such universal themes as love, solidarity, and their impending mortality. In its attempt to involve the audience in these conversations, the work demonstrates a faith in the public sphere as an arena in which differences can directly be stated, truth claims tested, and alliances formed that is conspicuously absent from the rest of the show. Ultimately, this latest Whitney Biennial feels less like a forum in which to debate the parlous state of the nation than a refuge from it.