“Here, the concept of ownership is abstracted until it disappears.” This is the official slogan of ExRotaprint: a former print-press factory collectively run as a mix of art studios, workshops, and community initiatives in Wedding, north Berlin, and one of four venues for the 11th Berlin Biennale. For about a year leading up to the exhibition’s opening, the curatorial team—María Berríos, Renata Cervetto, Lisette Lagnado, and Agustín Pérez Rubio—hosted a series of readings, screenings, workshops, and performances here which set the tone. Though interrupted in March by the pandemic that prompted the show’s postponement from June to September, the approach could be summarized as: “Here, the concept of curatorial heroics is abstracted until it disappears.”

Which is to say: this Biennale foregrounds work that addresses socio-political traumas past and present, and the effects of violence inflicted on the marginalized. (This is also how I understand the title “The Crack Begins Within,” borrowed from a line by poet Iman Mersal.) Despite curatorial texts that occasionally wax a little too poetic, the team circumvents the usual pitfalls of self-congratulatory gesturing and puffed-up wokeness that reduce artists and their works to issue-tokens or neo-ethnographic trophies. The works at ExRotaprint point towards the basso continuo of the Biennale as a whole: artists who create meaningful works with what would otherwise be the stuff of activists, psychologists, or historians, and who distill aesthetic grace from traumatic pressures. Or, in the words of the curators, in a joint statement issued before the pandemic disrupted proceedings: “We began by asking how to celebrate the complicated beauty of life as the world burns around us.”

The first work I encountered at ExRotaprint was a case in point. Kiri Dalena’s film Tungkung Langit (Lullaby of a Storm, 2012) is an intimate portrait of two orphaned Filipino children, brother and sister, in the aftermath of a typhoon that killed their family and washed away their home. Realizing that to interview these children would risk traumatizing them further, Dalena instead communicated with them through drawings and lent them a camera to film themselves. The disturbingly beautiful scenes that result are set in a makeshift hut surrounded by jungle. Treating people with respect and dignity is the premise of Dalena’s film, but the effect is less of stuffy moralism than a fairytale-like rendering of cruelty and trauma—something that keeps reappearing in the Biennale.

Also at ExRotaprint, the 1974 Uruguayan animation En la selva hay mucho por hacer [In the Jungle There Is Much to Do], by Grupo Experimental de Cine, immediately struck a chord, reminding me of watching similar Czech productions as a child. Based on the eponymous 1971 children’s book by Mauricio Gatti, this story about animals planning their escape from a zoo is visualized in a stop-motion, cut-out aesthetic and set to catchy hippie folk—but such cuteness can’t hide that this is an anarchist fable about anti-hierarchal solidarity. Walter Achugar, a founding member of the radical Montevideo-based film collective Cinemateca del Tercer Mundo (C3M), first encountered Gatti’s book while held captive as a political prisoner; upon his release, he invited three young C3M members (Alfred Echániz, Gabriel Peluffo, and Walter Tournier) to make this animation. The film was C3M’s last: in 1974, its members were arrested or forced to flee the country by the Uruguayan dictatorship. These events may seem distant, encapsulated in the Cold War era. But in Latin America—from where many of the artists in this Biennale were selected, by a curatorial team steeped in the continent’s discourse—they are closely related to artists’ and activists’ contemporary struggles for minority rights in the face of harassment and prosecution, not least during the pandemic.

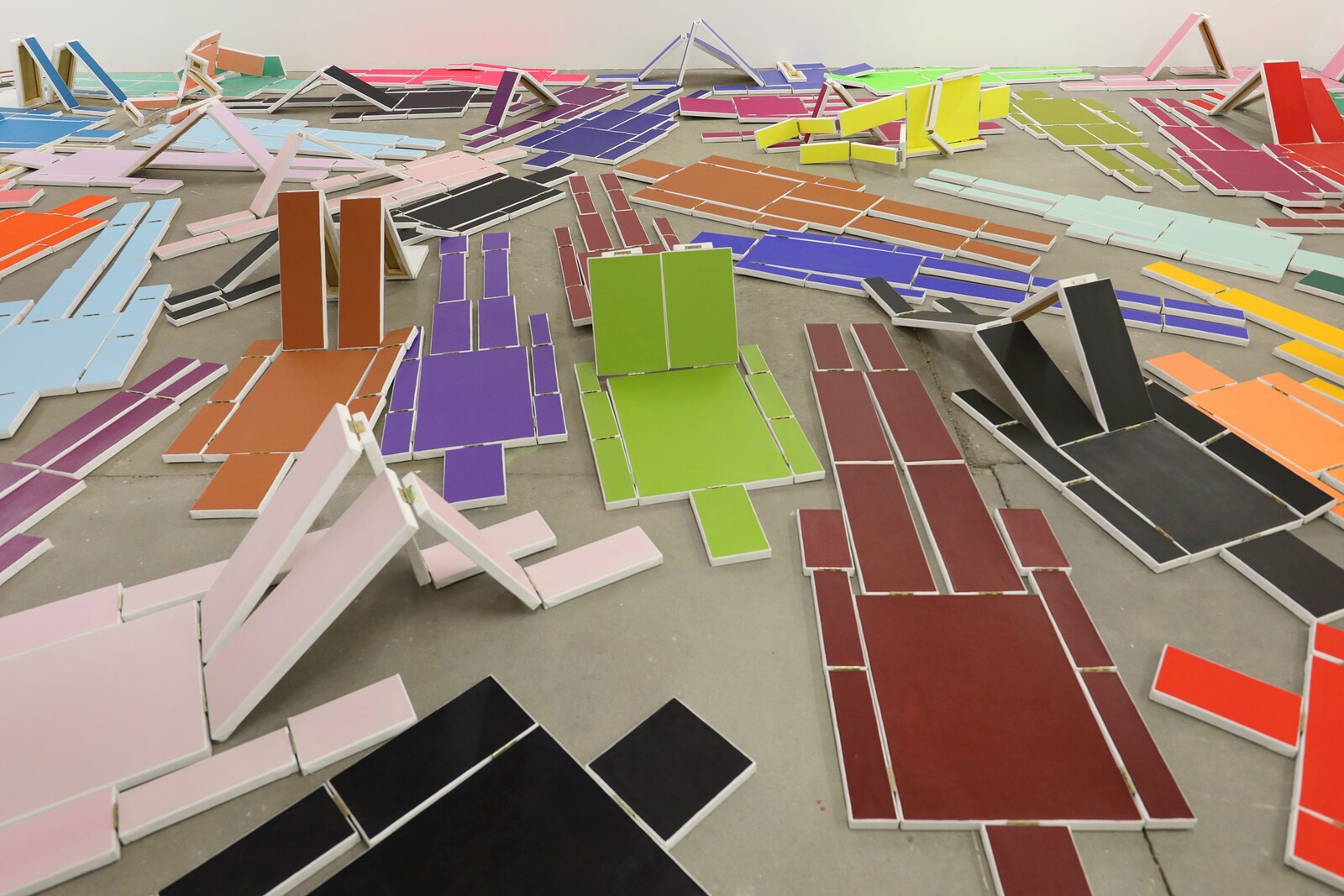

At KW Institute for Contemporary Art, two works wrested strong images from current events. Mariela Scafati’s Movilización (Mobilization, 2020) fills the gallery’s first ground-floor space with monochrome canvasses in various colors. Hinged together to form abstracted outlines of human bodies lying flat on the floor, or with legs bent, they resemble fugitives pausing for breath, or tightly packed prisoners. As the title suggests, the Buenos Aires-based artist initially conceived these figures as standing, like a crowd of protesters. But when Argentina’s lockdown interrupted feminist demonstrations against a string of femicides, Scafati instead decided to conjure a moment of fragility and rest.

On August 4, in São Paulo, the Teatro da Vertigem collective staged one of the most powerful performances I’ve encountered in years, documented here in a short, elegantly shot film displayed on a single flatscreen. Filmed at night, a motorcade of more than a hundred cars drives slowly in reverse gear down Paulista Avenue, in the city’s financial district. That the participants wear protective masks contrasts with the unhinged voice of Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro—who described Covid-19 as “just a little flu” and discouraged mask-wearing—speaking over the soundtrack as the cars continue to Consolaçao Cemetery, passing a white banner featuring a drawing of an old woman lying on her deathbed in agony. The drawing is by Flávio de Carvalho (1899–1973), the Brazilian artist and architect whose work inspired a central aspect of the performance—that the cars are driving backwards. In his 1931 work Experience No. 2, Carvalho walked in the opposite direction, without removing his hat, through a crowd of worshippers during a Corpus Christi parade in Saõ Paulo, inciting an angry and violent response. (Several other works by Carvalho are on show or documented throughout the Biennale.) Teatro de Vertigem’s car-procession-as-funeral-march captures the bone-chilling, dystopic feelings induced by the far-right Bolsonaro government and its enablers, who with their Covid-19-denying and racist policies appear willing to kill their own people.

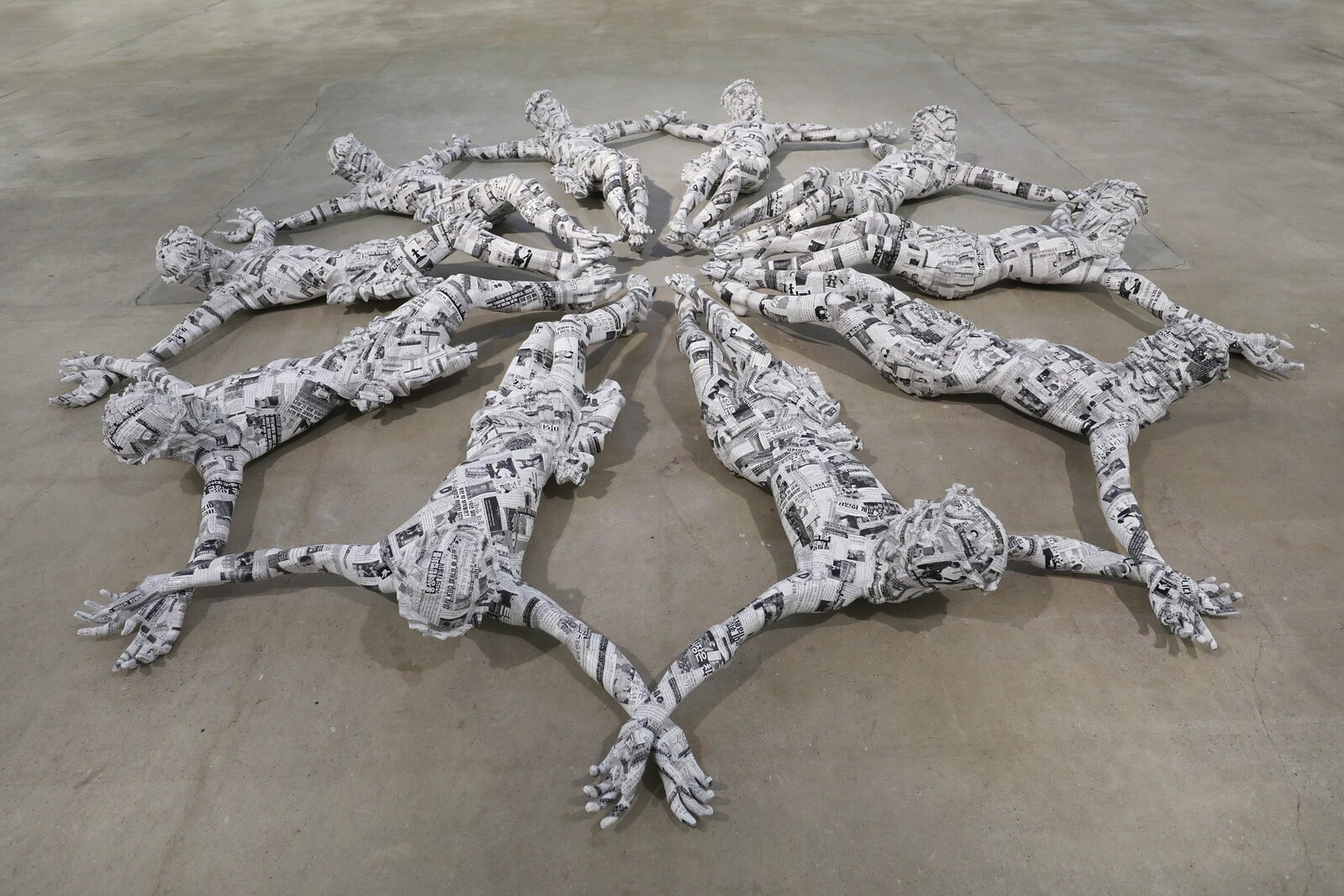

Granted, these works won’t cheer you up. But catharsis can hold its own kind of grim humor, as expressed in the grand central space of KW, which has been transformed into a kind of church. At the center, ten life-size statues of Jesus, by Young-jun Tak, form a circle on the floor, their bodies plastered with the homophobic pamphlets routinely handed out in South Korea by Christian fanatics. The title, Chained (2020), references how these groups attempt to stop Pride parades in South Korea by chaining themselves together and lying in the street.

Such bigotry is also expressed in a series of paintings by the Brazilian artist Pedro Moraleida Bernardes, who died from suicide in 1999, at the age of 22. A polyptych is suspended like an altar piece just behind Tak’s Jesus circle; the six panels depict—in brute, neo-expressionist manner—scenes of lust, violence, and debasement. Some of the figures sport smiling pig-heads in front of large church crosses, while the work’s brilliant title is scribbled on top: Sentindo um cansaço mortal por representar o humano, sem fazer parte do humano (Feeling a deadly weariness of representing humans while not being part of humanity, 1997). In remedy to Bernardes’ dark wit, Florencia Rodríguez Giles’ monumental black-and-white pencil drawings, from the 2018 series “Biodelica,” project a utopian wonderland in which human bodies, at once muscular and slender, defy binarism in favor of a luxurious, graphic, and lustful polymorphousness.

The theme of religiosity that lingered in KW was modulated in Gropiusbau towards shamanic rituals. I have difficulty relating to shamanism, not because I can’t believe that spiritual practices communicate wisdom, but because I don’t think they should be exempted from critical enquiry—which is occasionally the case in the solemn and subdued presentation of such work in this exhibition. My reservations admittedly have a lot to do with Germany, and Berlin, where certain esoteric ideas—of tradition, healing, purity—have typically been compatible with the far right. Which is not to say that videos such as Francisco Huichaqueo’s Kuifi ül (Ancient Sound, 2020) or Antonio Pichillá’s Blows and Healing (2018), documenting their actions following traditional spiritualist practices, are inherently problematic; only that, without a pronounced and counter-intuitive contextualization, they might inadvertently cater to sentimental desires for othered authenticity. Which helps explain why I enjoyed Bartolina Xixa’s Ramita Seca, La Colonialidad Permanente (Dry Twig, The Permanent Coloniality, 2019), a music video in which the Andean drag queen, who is of the Coya people of northern Argentina, dances in the middle of a dire dumping ground. Clad in a mix of traditional indigenous and flamboyant contemporary attire, she denounces the ruthless neo-colonial extractivism of companies such as Monsanto with exhilarating verve.

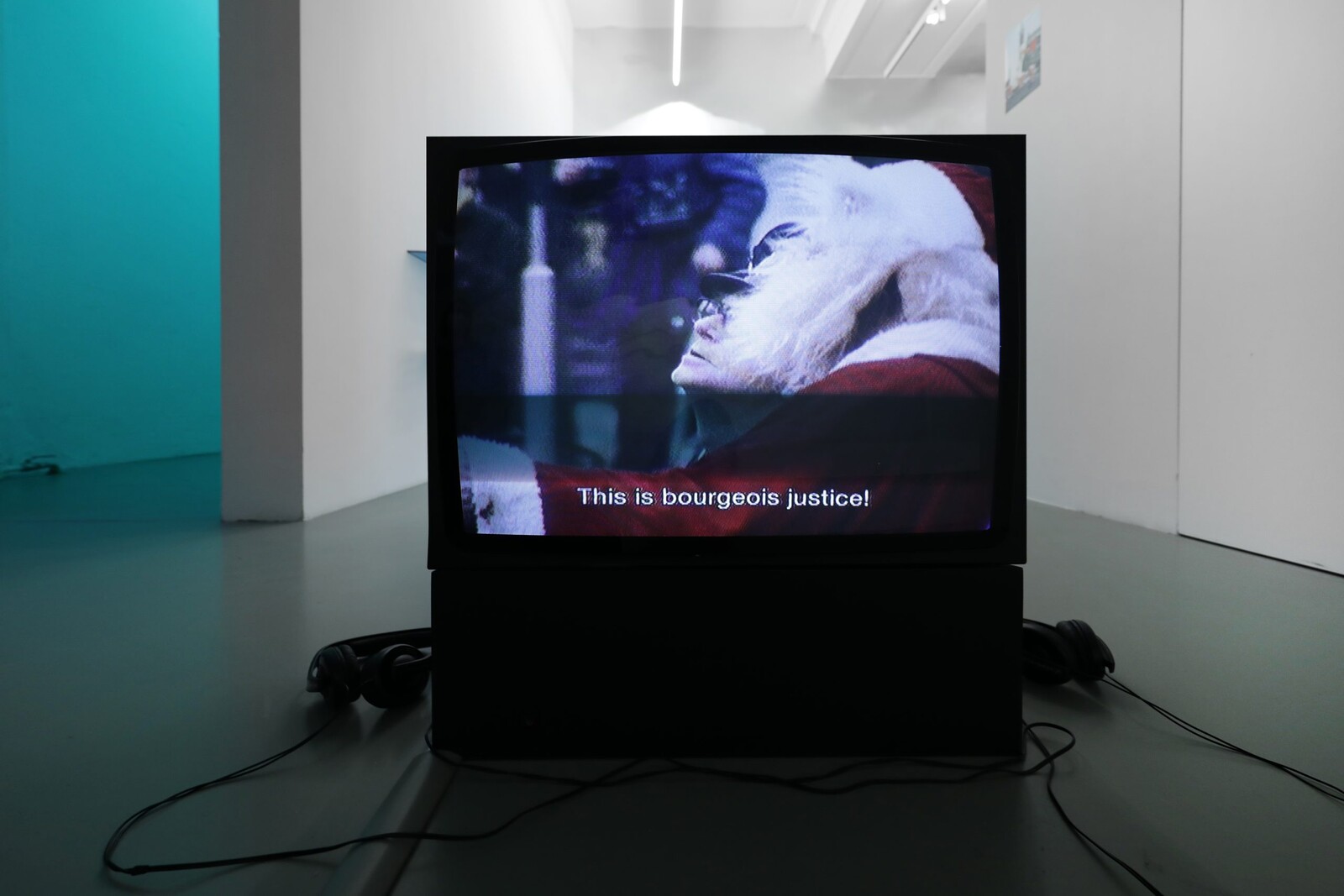

Maybe this is the key to the question of spirituality in contemporary artworks: they are rewarding when unexpected and counter-intuitive combinations come into play, protecting them against the danger of reactionary simplification while at the same time aligning them with the probing nature of true spirituality. At daad gallery, two of my favorite works exemplified this. One is by Delaine Le Bas, who installed a lively window-display of playfully makeshift clothing in homage to St Sara Kali George, a merging of two patron saints of the Roma people. Together with an animated video clip, these pieces celebrate the undetermined sexuality that this new holiness stands for. The other is a historic piece. In 1974 the Solvognen (The Sun Chariot) Theater Group—which originated in Copenhagen’s autonomous alternative neighborhood of Christiania—formed an army of 100 Santa Clauses. Men, women, and children dressed in the standard red costume and beard roamed the streets of the Danish capital, first distributing the usual signs of spiritual comfort—giving away hot chocolate, singing carols, etc.—before diverting into increasingly radical protests and announcements calling for motor factory workers to become owners, or causing an anti-consumerist fuss in a department store. What’s thrilling about this piece is the way the otherwise standard Marxist critique is conveyed and circulated via the aesthetic subversion of an icon standing for both folksy tradition and capitalism.

Many of the works in the Biennale process existential, sometimes life-threatening experiences. The point is that powerful aesthetics grow from that process, and not just as a side-effect but as a medium and source of emotive perception and intellectual insight. I therefore have little left to say to those who believe that the success of these pieces hinges on quantifiable political effect, or to those for whom such work is too “identity politics” or simply too “political” to be art proper in the first place, other than: go look again and open your eyes.