June 10–September 10, 2023

If history is written by the victors, asks Christopher Kulendran Thomas’s exhibition, is reality a construct of the dominant narrative? What then does it mean to write a history of the defeated? The artist’s work starts from the struggle for Tamil independence during the 1983–2009 civil war and its aftermath, and moves onto the larger questions that arise from its failure. Reflecting on the ethnic oppression that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and forced his family to flee the country, Kulendran Thomas’s collaborations with Annika Kuhlmann suggest that art can influence our perception of not only history but reality itself. Mixing historical facts, storytelling, fiction, and deepfakes, his work offers a glimpse into a reality that exposes the dominant one as just one well-told version of many.

The two previous iterations of this exhibition—at London’s ICA and Berlin’s KW—opened with the struggle for utopia before moving on to contemporary art: at Kunsthalle Zürich, the order is reversed. The looping twenty-four-minute video Being Human (2019), installed within a plywood construction, is the first video to encounter when visiting the exhibition and it reflects on the relationship between the end of the war and the flourishing of contemporary art in Sri Lanka. Kuhlmann and Kulendran Thomas combine talking-head interviews about the art scene with the reflections of Norwegian-Tamil artist Ilavenil Jayapalan as he journeys around the island and computer-generated avatars of Taylor Swift and Oscar Murillo. “Every artist wants to be authentic,” says Swift’s avatar, as an amalgam of her songs plays in the background. It’s one of several moments in the show resembling memes in their ability to condense intersecting realities into pithy aphorisms. Being Human speaks with, rather than about, technologies such as deepfakes and network-generated music, using them to illuminate the reality of a conflict largely lost in the global attention economy.

Surrounding this work is a series of large-scale paintings that fill the walls of the vast hall. These are the result of another network-generated twist, emerging from visual art by Kulendran Thomas’s contemporaries that is publicly available online. An artificial neural network created by the artist searches the images for their common denominators: the recognizable motifs of western art-historical influence. It generates new images from these patterns in the form of .png files, which are then painted on canvas in the artist’s studio. Kulendran Thomas mimics the painter’s creative process in an accelerated, digitally processed manner in order to blur the line between machine-based processes and their human counterparts.

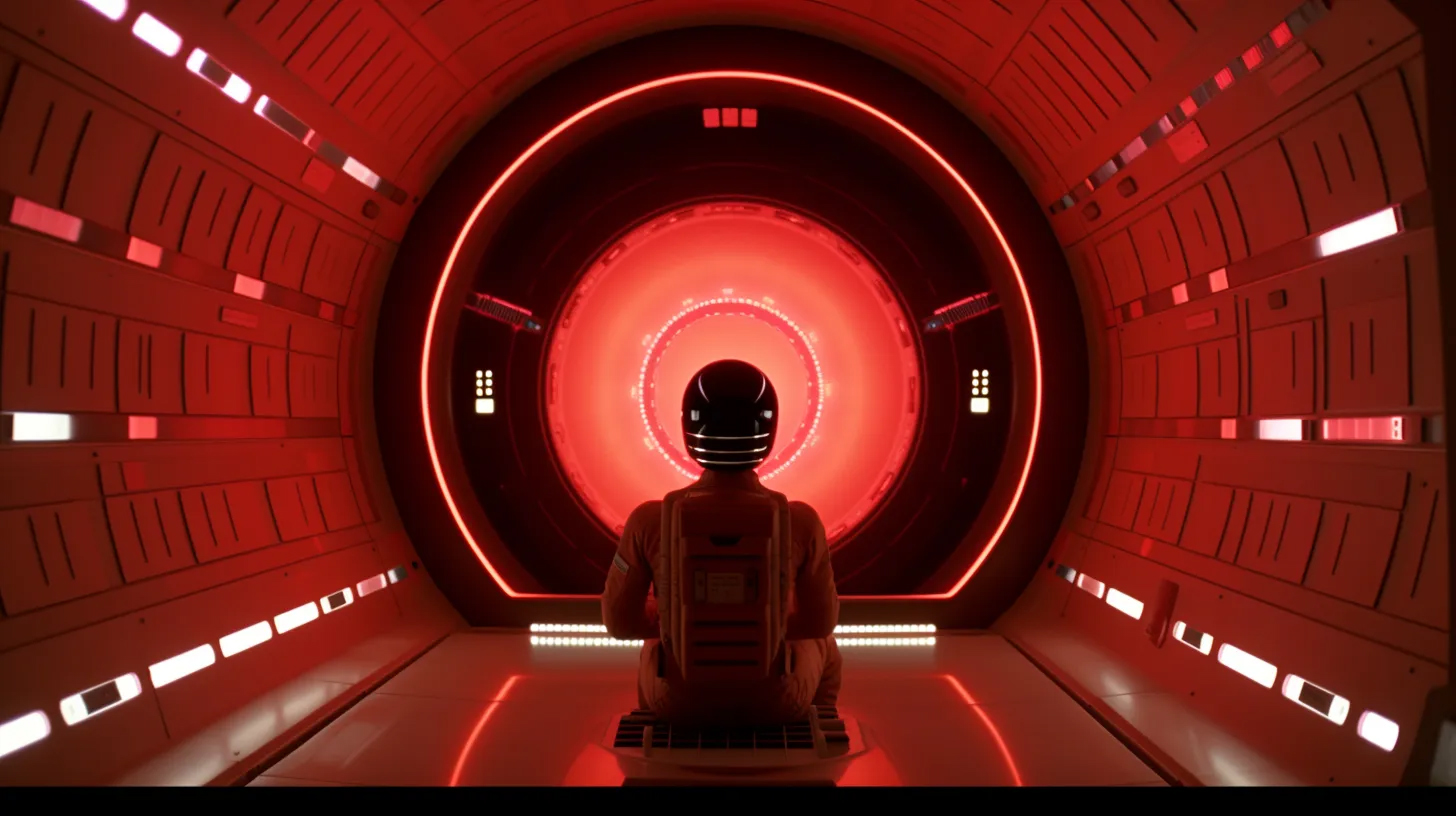

This fluidity of authorship and its processes extends to the inclusion of other artists’ works, such as Kingsley Gunatillake’s sculptures or reliefs and masks by Tamil artist Aṇaṅkuperuntinaivarkal Inkaaleneraam—at these times, Kulendran Thomas’s solo exhibition mimics a group show. The latter works refer to the Tamil art scene, the development of which was made impossible by the civil war, and offer a prelude to the video installation The Finesse (2022/3). Viewers are stationed between two wall-sized video projections, one of which shows the lush jungles of Sri Lanka’s north. The glass panels onto which the narrative section is projected are of varying heights and multi-channel. While it also combines computer-generated avatars with Tamil history, archival footage, and the big questions of our mediated reality, a world-building mode is at the core of the video.

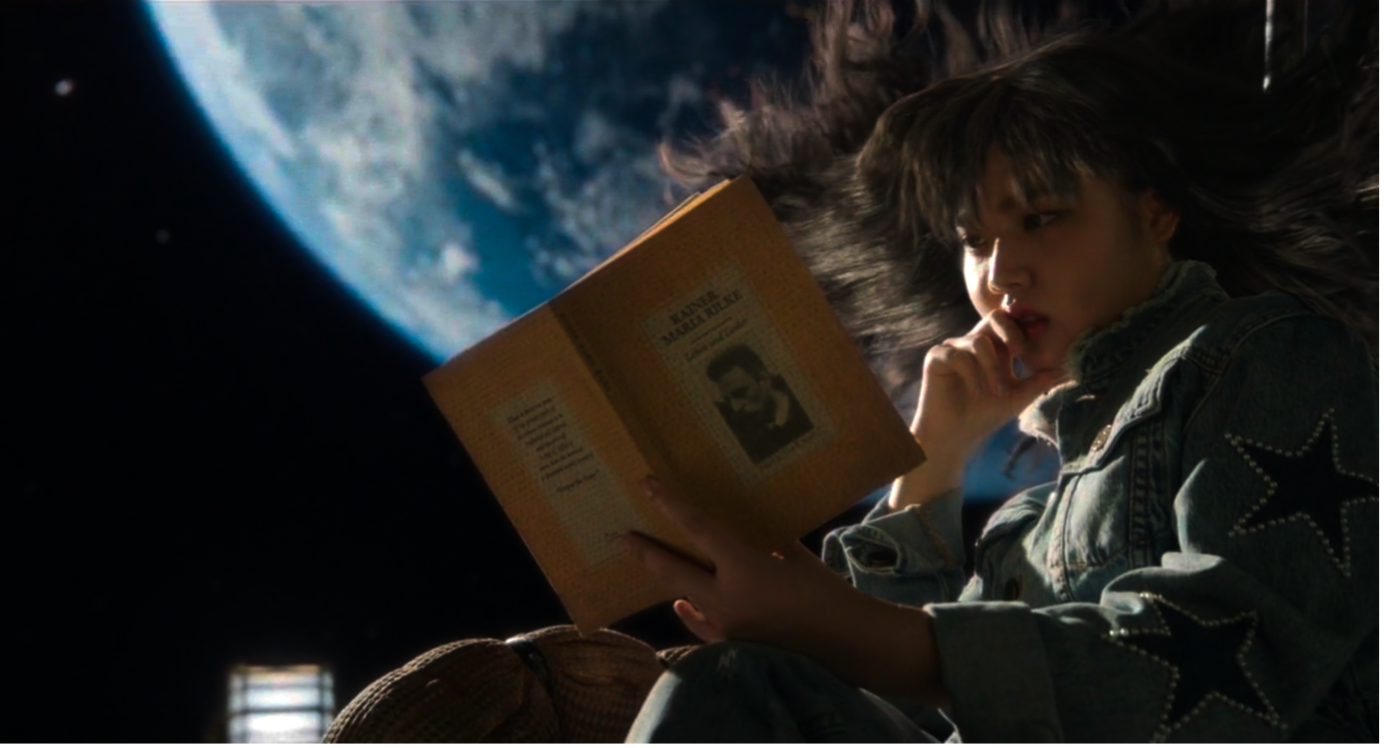

For a period during the civil war, the region of Tamil Eelam operated independently as a de-facto regime. Here, it is presented as a utopia—self-sufficient, cooperatively organized and dedicated to the common good. A uniformed soldier illustrates these ideas as she travels through the jungle, reveling in Tamil Eelam’s architecture which reimagined infrastructure; a place where artists worked toward collective liberation rather than individual expression. Tamil dancer and filmmaker Asmina Thirunavukarasu, who appears throughout the video to share her thoughts during a bus trip and in a discussion group, brings in the perspective of the diaspora: “Our history has been erased, why not reinvent it?” The artist’s studio has also previously translated such ideas into exhibitions that transcend the classical art context. New Eelam (2016), for example, is a start-up that rents out communal housing by subscription in various metropolises around the world, and conceptually draws on the same approaches.

The world-building that occurs here is believable. Even when a fake Kim Kardashian is speaking, she says things that are, unfortunately, all too true: as a person of Armenian descent, she tells the viewer, she has a clearer view of what people who only know westernized reality might think is the only true one. This is preceded by the soldier’s statement describing reality as what empires perpetuate. “Being Tamil means understanding reality as fiction,” Thirunavukarasu says at one point. “FOR REAL” makes a strong case for the importance of artistic production in that light. On my way out, Tay Tay’s phrase from upstairs echoes with me: maybe simulating simulated behavior is the only way we have to be “for real.”