Nine months since the pandemic first hit New York, it is hard not to be moved by Salman Toor’s tender and luminous paintings, fifteen of which make up “How Will I Know,” his first solo show in a museum. In them young queer men gather inside and outside bars, dance joyously in apartments, embrace tenderly, and chat quietly on stoops and sofas, banal scenes of everyday intimacy and sociality that our seemingly interminable forced isolation has rendered both unfamiliar and precious. Skillfully composed of accumulations of short sketchy brush strokes, they picture the innocent ease of pre-pandemic revelry when the simple act of coming together was still untainted by the invisible threat of contagion.

Though inspired by moments from his life, Toor’s scenes are composed entirely from memory and imagination, and form visual analogues to the literary genre of autofiction, as co-curator Ambika Trasi persuasively argues in an accompanying essay published online. Some are given a dazzling emerald tint, energizing their quotidian settings with the buzz of dreamy fabulation. Toor conceives of his slender young male figures as marionettes, a quality emphasized through their slightly elongated noses á la Pinocchio. However, their sleepy downcast eyes, drooped shoulders, and limp, almost tentacular limbs do not suggest a lack of vitality or agency so much as embody a relaxed intimacy as they lean into and cradle each other in warm and protective embraces. Even before the pandemic hit, Toor’s focus on spaces and activities of urban leisure, intimacy, and community were not merely escapist fantasies or articulations of emergent queer subjectivities. Rather, as contemporary updates of what art historian T. J. Clark, in his 1985 book on Impressionism, dubbed “the painting of modern life,” they index profound transformations in the contours of social life in America.

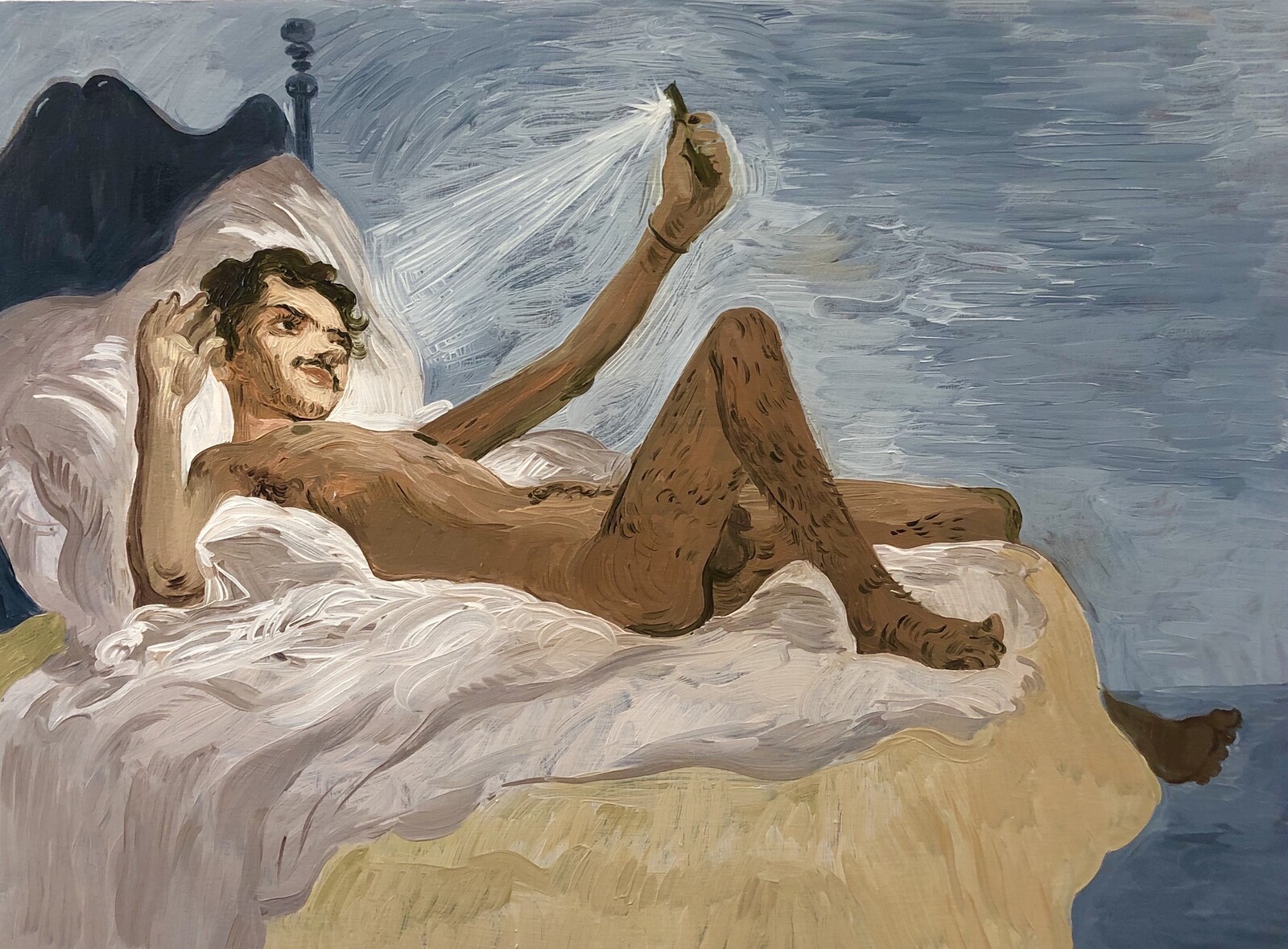

Toor has long held an interest in European Old Masters, and his paintings are rich with allusions to western art history, from Mannerism’s languorous bodies and the object focus of the Dutch Golden Age to the frothy frivolity of the Rococo. A 2019 painting not included in this exhibition, The Bar on East 13th Street, knowingly repeats the iconic composition of Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), replacing the bar girl with a young Brown man. At the Whitney, the tondo format of The Star (2019) and the portentous title of The Arrival (2019), which seems to secularize the holy high drama of scenes like the Annunciation and Visitation, echo traditions of Christian art, as do the streaky halos and shafts of light that subtly spotlight his protagonists. Updated for the twenty-first century, the source is no longer divine but technological, radiating from the smart phones and laptops that feature prominently in Toor’s paintings. Functioning as both portals and mirrors, thresholds and interfaces, these prosthetic screens have become indispensable nodes through which our social relations increasingly unfurl. In the midst of all the camaraderie, Toor’s protagonists often appear isolated and melancholic, captivated by screen-glow, drawing a subtle distinction between being connected and being together that has only sharpened during our months of pandemic isolation. Rebooting the tradition of the odalisque, in Bedroom Boy and Sleeping Boy (both 2019), Toor replaces the female nude with a slender and hairy naked Brown boy, his face and body resplendently studded with prickly black dashes, whose body is on display not for the viewer but for a virtual interlocutor. Such devices have reorganized and problematized not just conventions of sociality but also constructions of the gaze, which now extend through the screen to circuits of desire outside the psychological space of the painting.

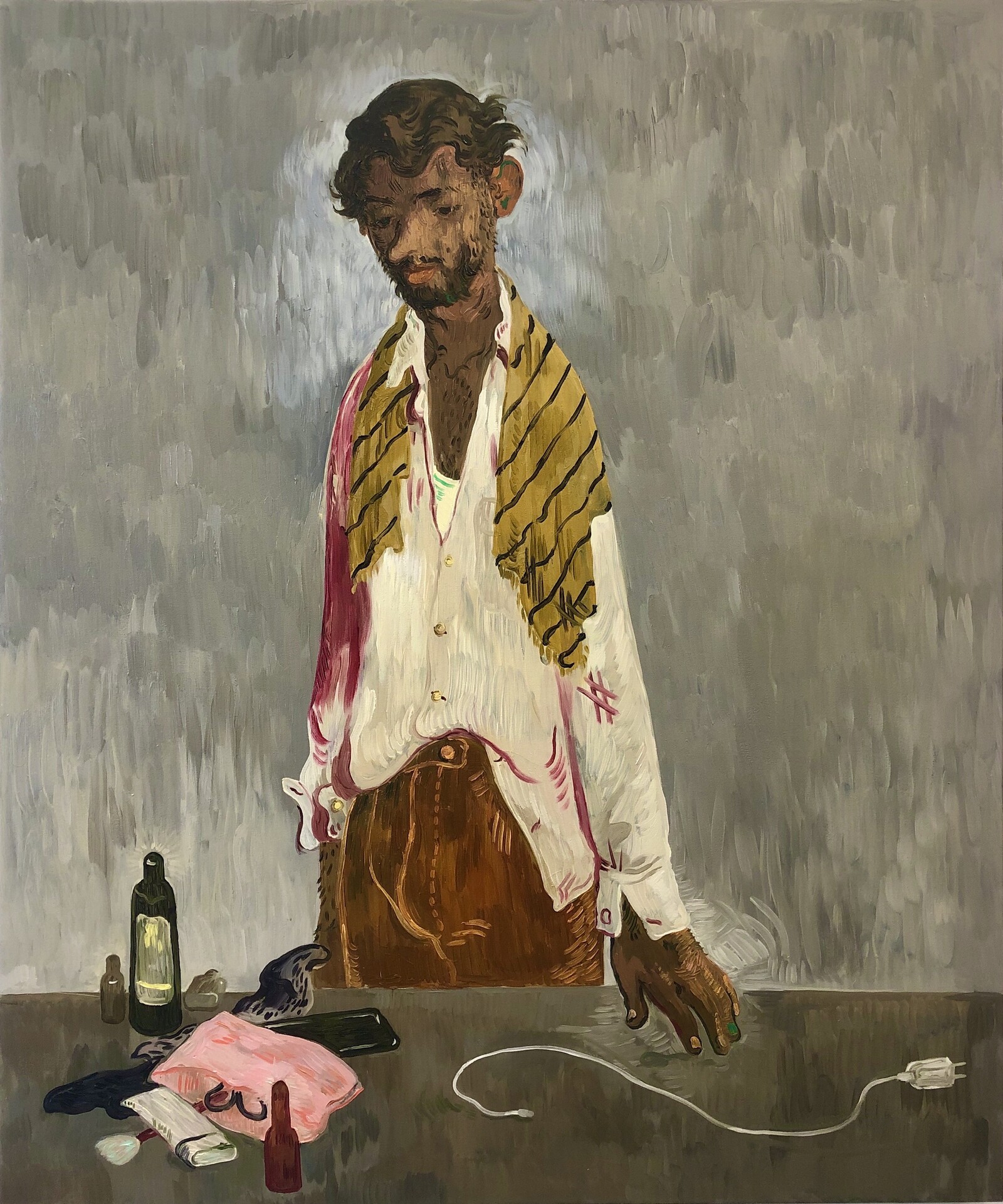

The exhibition also includes two works from an ongoing series that show figures sullenly standing in front of a table strewn with various personal objects, picturing the secondary screenings to which South Asian men have been frequently subjected upon entry into the United States post-9/11. The repeated frontal format places the viewer in the position of the scrutinizing US Customs and Border Patrol agent. Such agents of discipline and surveillance reappear in other paintings, lurking at the margins, threatening to disrupt the safety of idylls of gay sociality. Together, Toor’s paintings suggest that a racialized queer subject emerges not just through acts of individual discovery and articulation or collective communion, but against the incessant impositions, projections, and judgements of the normative gaze, through what queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz dubbed “disidentifications.”

Parts and Things (2019) is a powerful visual allegory of the subtle violence of this process of trying on and shedding often conflicting traits and behaviors to finally arrive at a satisfactory composite: an unruly heap of heads, torsos, and limbs spill out of the proverbial closet. But what really makes the scene click is the seemingly insignificant details, for which Toor has a knack: a naked light bulb—a fanboy reference to Pablo Picasso and Philip Guston—illuminates the cramped space; a solitary deformed wire hanger screams twenty-something New York; and a feather boa snaking through the bodily fragments adds just enough levity to normalize an otherwise grotesque scene. Pinocchio dreams of becoming a “real boy.” Pitched between dehumanizing regimes of racialization and surveillance, complex processes of self-articulation and assimilation, joyous rituals of community and desire, and the constant and alienating distractions of social media, Toor’s paintings quietly reveal just how fraught a process that can be for a queer South Asian man in the US.