In 1970, Sonya Rapoport unlocked an antique architect’s desk she had purchased a decade earlier and discovered a trove of geological survey maps from the early 1900s. Using the information on the maps as a starting point, Rapoport began drawing and embroidering directly on the sheets in what she called her “Nu Shu language,” a visual lexicon the artist developed in reference to a tongue used only by women in the Hunan region of China. As the artist tells it in a 2006 essay, this moment marked an aesthetic shift, opening a new line of creative inquiry that would anchor her practice for decades.1

The artworks exhibited at Casemore Kirkeby, however, make clear that in fact there were inklings of these developments a few years prior to the artist’s revelatory moment with the maps in the desk. Here, in a selection of sculptural paintings made from 1964 to ’67, Rapoport uses upholstery fabric as her primary substrate, both for tracing the gaudy floral patterns in paint, and for stenciling curvilinear, abstract forms that mark the first instances of the artist’s transcription of her visual language into her artwork. Viewed alongside several drawings made during the same period, the exhibition reveals Rapoport as a process-based artist whose primary medium is information.

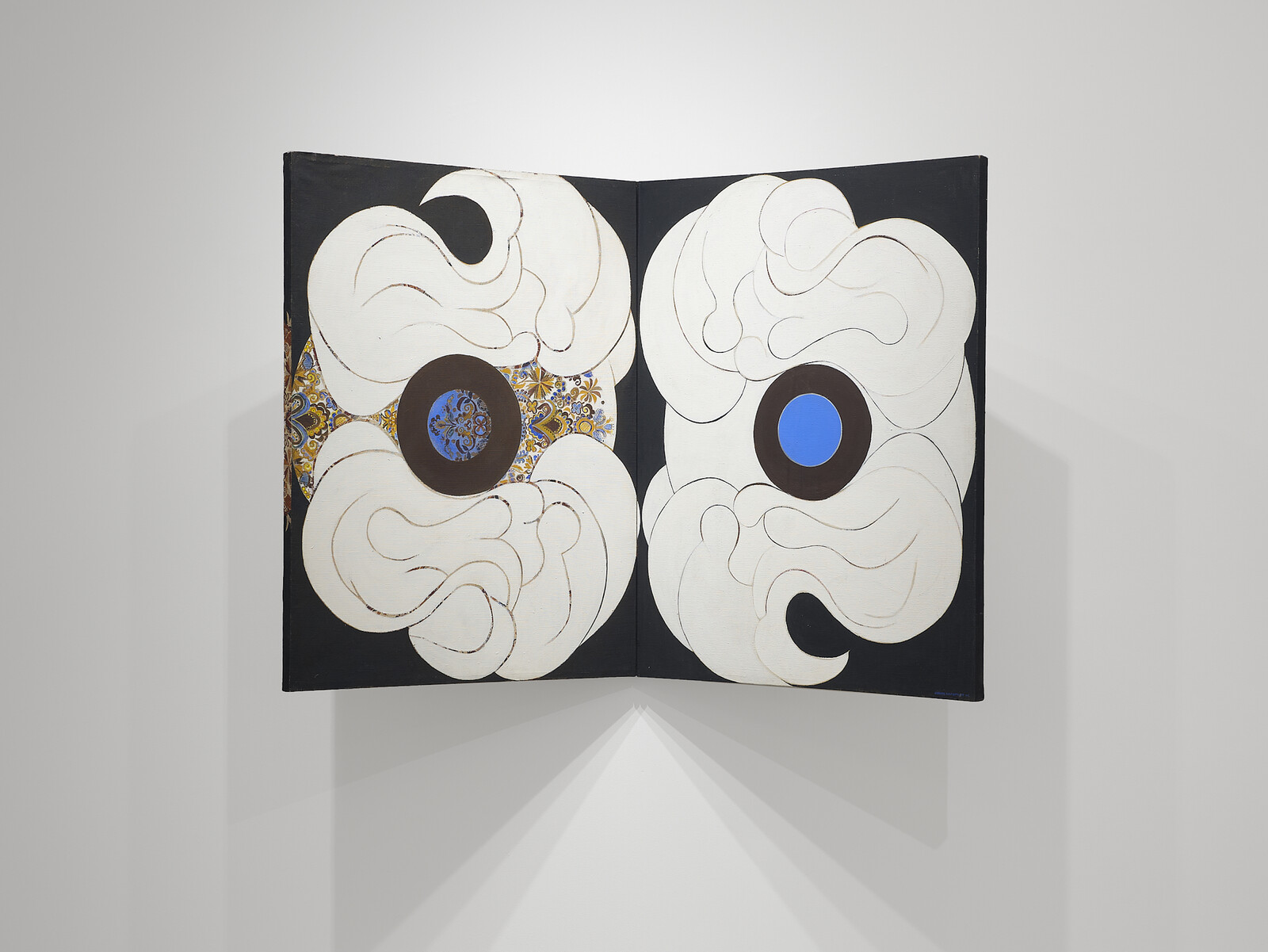

Directly across from the entrance to the exhibition is Bullseye (1966). Here, two large canvases are joined at an angle and affixed to the wall, like a big open book, revealing on each panel an abstracted white organic form bright against a dark ground. Rapoport attributes time spent studying with Erle Loran at UC Berkeley, and delving into his 1943 text, Cézanne’s Composition: Analysis of His Form with Diagrams and Photographs of His Motifs, as influential in her approach to composition, not just in terms of form and perspective, but as a means of diagramming her ideas.2 As such, closer examination reveals a careful systematization working within each panel. On the right, Rapoport completely obfuscates the gaudy floral upholstery fabric she uses as her substrate: we see a solid black background behind a white stenciled form encircling a cerulean, eye-like orb in the center of the canvas. Opposite is a fastidious game of hide and seek starting from the leftmost edge, where she shows a small slice of the original, unaltered fabric. From here, the flowery pattern creeps across the canvas, but Rapoport has painted over it, amplifying the colors, iterating within the system of the found textile to create her work.

Across the gallery, Memoralia (1967), made just a year after Bullseye, is one of the strongest works in the exhibition, and shows further play with adding and manipulating information within an existing system. Here, the artist stacks two canvases, both covered again with upholstery fabric. We don’t see much of the bottom painting: it is slightly larger than its sister, and with just a few inches of the red and orange painted blooms revealed all the way around, it serves as a kind of dimensional frame for the artwork as a whole. On top, once again, is a loud flowery upholstery fabric, selectively traced and painted over by Rapoport. In two columns repeating vertically down the canvas, the artist stencils on a graphic, white shape that is at once a uterus and a blooming calla lily. In the negative space between each repetition of these patterns, the artist delineates another wavy, perhaps vaginal, organic form by painting over the upholstery pattern with an even, rich golden yellow. In Memoralia, these distinctly female, repeated shapes across the artwork are carefully plotted shifts and amplifications within the artist’s source material.

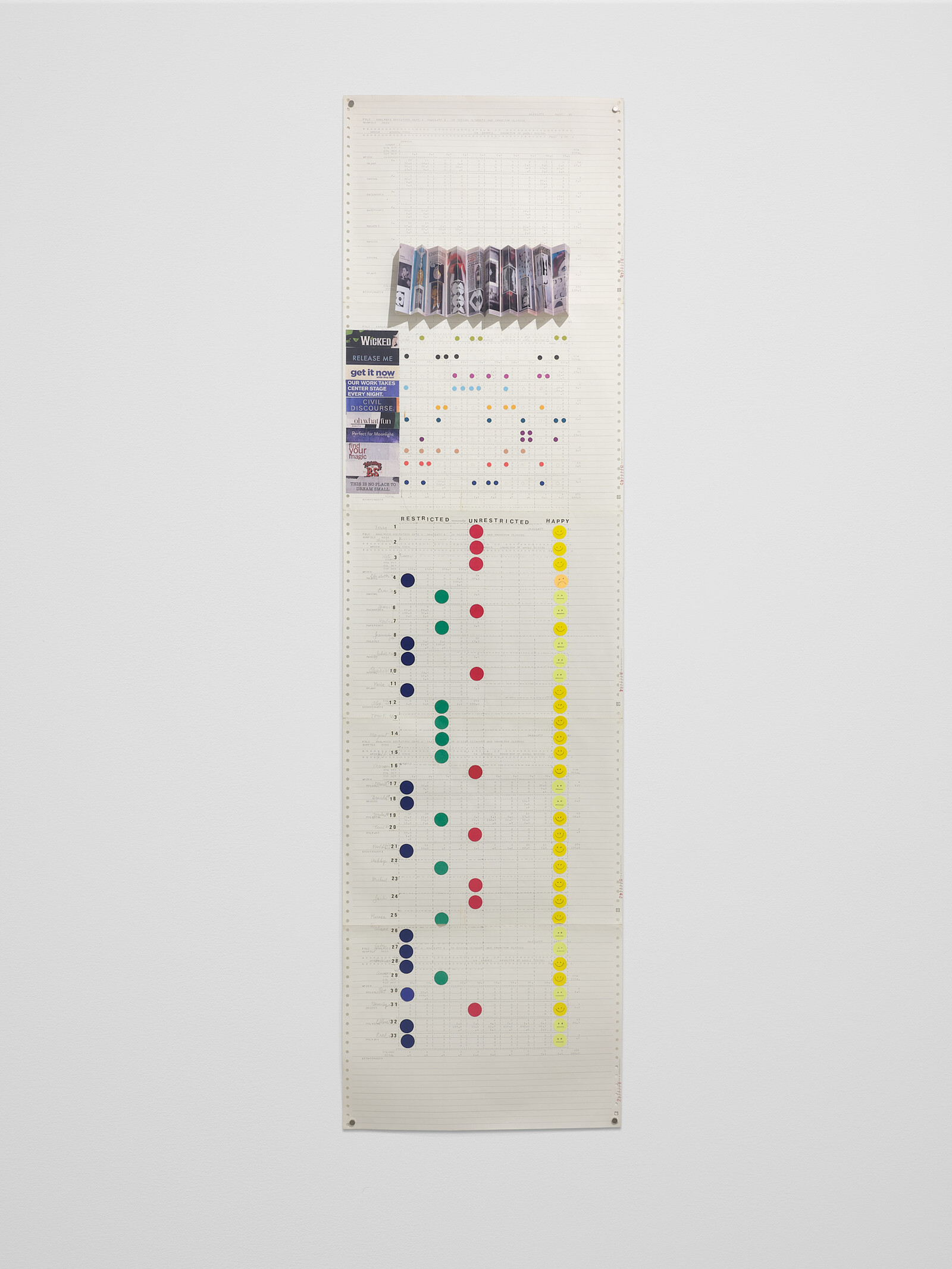

The back gallery showcases imPOSSIBLE Conversations, a 2013 installation-based work that carries the thread of these early experiments forward into work made before Rapoport’s death in 2015 and expands their possibility for manipulation and iteration by adding a social dimension. Drawing on Alvin Roth and Lloyd Shapley’s economic theories about how audiences, institutions, and companies form stable matches within markets, Rapoport made black-and-white, 8 x 10” photographs of a selection of these early fabric paintings, and then paired each with an advertisement page from editions of The New York Times to form a collaged, composite artwork.3 She then invited ten viewers to assign a headline from other advertisements to the ten artworks, installing the new headlines directly above the composites. The resulting pairings are uncanny: both in the way her paintings echo the forms in the advertisements, and in how the viewers assign content and even humor to the visual information. In this work, as across this show, Rapoport is an artist-engineer, coding and riffing on the internal structures of her artworks to create new visual data for the viewer.

Sonya Rapoport, “Digitizing the Golem: From Earth to Outer Space,” Leonardo 39.2 (2006), 117-8.

Richard Cándida Smith, “A Throw of the Dice: Between Structure and Indeterminacy,” in Pairing of Polarities: The Life and Art of Sonya Rapoport (Berkeley: Heydey, 2012), 26–7.

A summary of Roth and Shapley’s ideas is available online via the Swedish Academy of Sciences: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/popular-economicsciences2012.pdf.