Like a thesis hidden in a footnote, a small projection in one corner of an exhibition of junkyard complexity shows a loop from John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), starring John Wayne and James Stewart. In the scene, Stewart’s character, a lawyer in the frontier town of Shinbone, sits before a schoolroom full of kids and adults. He’s learnin’ them readin’ and writin’, where no one else will. He is also, lawyerly, teaching them about the law of the land, paraphrased thus: “The people… are… the boss!” It is a lesson in the John Ford mold—as self-evident and patronizing as Stewart’s words of praise: “That’s fine. That’s just fine.” The same goes for the film’s plot, which pits the outlaw and rustler Valance against the fence- and property-line-loving townsfolk, who just want to raise their sheep in peace. The film is a latter-day Ford allegory: “liberty,” an old idea, must be gunned down, now that we’ve outgrown untrammeled, unfenced ranges and need regimented “lots,” “towns,” and “ranches” instead. REDCAT being an exhibition space and not a grade school, the viewer is encouraged to be skeptical about the purity of such motivations as the anti-entropic philosophy of manifest destiny—the poetic doctrine of American endo-imperialism, which would link increased civilization to increased order. Civilization, in John Ford films, is unironic; in practice, not so much.

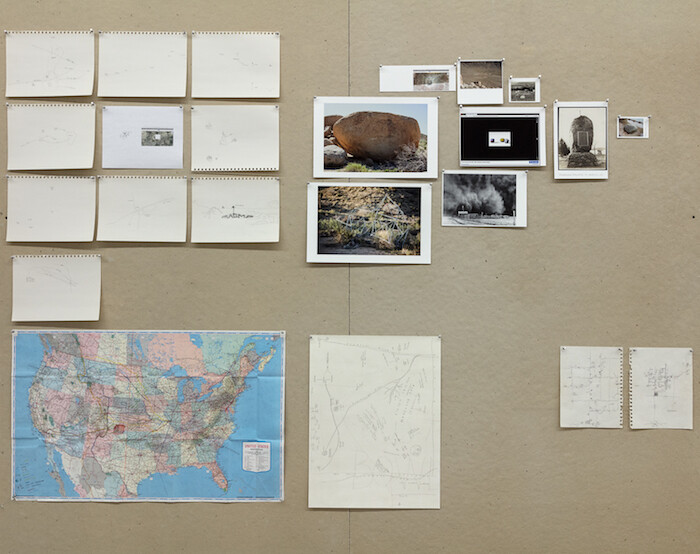

Dave Hullfish Bailey’s “Hardscrabble” is a lesson, too. The Liberty Valance schoolhouse scene is projected onto the back of a full-size model of the Sputnik satellite. The ball-like surface is comprised of triangular panels, after geodesic architecture and design—construction that approximates the strength and realism of spheres and curves using only straight lines: the way the US Constitution is described as a “frame,” to be filled with specific cases; the way arcane disciplines are available to the layman only in outline. The artist is expected to be a generalist, to know a little about a lot, including that their image of any one issue is lower-res than that of experts. Bailey plays on this with displays of graphs and maps, folded or pixelated, in a way that asks just how granular—how scalable—are laws and other boundaries. Clippings pinned to sheets of insulation link the tensegral structures of Drop City, the commune in southern Colorado; the Pentagon; and a school table with the same pentagonal form. A pro-fracking mailer follows records of Colorado’s prevailing winds.

The show is grouped in four zones, each relating to a project about a different “planned community” or off-grid experiment in the American West. They don’t exactly correspond. It’s as if, just as the “planned” community resists the conventions of city planning, so does Bailey’s show try to circumvent certain concessions to legibility. The area dedicated to the geodesic Drop City, for instance, comprises maps intricately, regularly folded into peaks and valleys connected edge to edge and supported by a construction of steel wire and steel fence posts, as well as other maps on tables, the Sputnik model, and the John Ford clip.

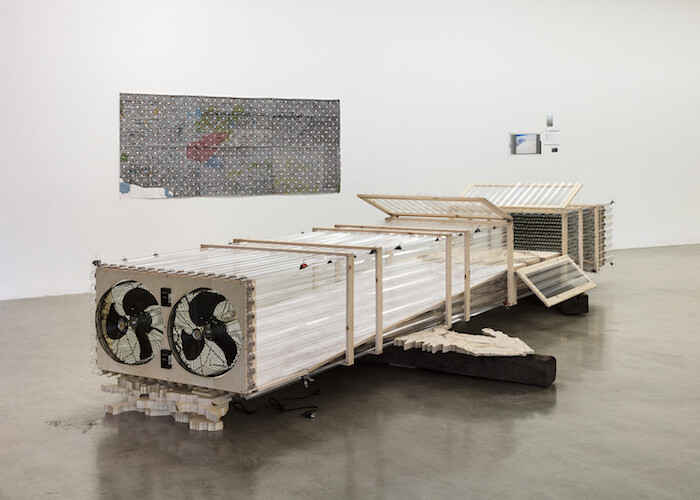

The largest structures in the exhibition are “rigs” meant to function in another time and place: a wind tunnel with the fans unplugged, a printer/scanner without power. In one corner, on a dirt-brown tarp, slides of Smithsonesque phrases flash with the rhythm of his 1972 essay “The Spiral Jetty”: “Northeast by East—Parenting, Gender/sexuality, sand, rocks, prison, access road”; “West – Other Media, Romance, sand, salts, carbon dioxide wells, mud, saltwater.” Nearby is a truck tailgate, black and smooth and never used, one end propped up by a metal sawhorse and the other by shelving made of sawed-off decking. On these canted boards are the green-bound volumes of West’s Annotated California Codes, a scholar’s edition of the state laws. There are nine volumes concerning water. Penal: 11 volumes. Health and safety takes 27. The printer/scanner sits on the tailgate, as if you could make your own copy of these obtuse rules (from a prohibitively expensive bound set, no less). It’s a nod to democracy, or the democratization of law—but it’s unplugged: the idea is petrified. What remains is Bailey’s habit of leaving reading material “lying around,” providing a syllabus without direction or order.

Teeming with material, yet short on didactics, Bailey’s loose historical treatise turns out to function better as a lesson on lessons themselves. “Education” hardens into “pedagogy”; from something somewhat innocent-sounding and passive to something activist and aggressive, even—a “hardscrabble” idealism. In the end, these sculptures don’t give out information so much as redistribute a field of references—the rubric of Robert Smithson, in short, who himself combined earth art and science fiction, geology and urban planning, Buckminster Fuller and the hysterias of cold-war modernism. Bailey seems to find art better suited to such a loose exercise than to plain teaching—square with art’s disposition to be poetic, allusive, and opaque—to operate less on solid, arable terrain than on aporia.

Perhaps this is why, under a circular reading lamp, sunflower seeds rest in small pucks of soil. (At the time of writing, there are no sprouts.) This micro farm echoes, on the other side of the installation, several inflated inner tubes, like germination stations at human scale. These accompany a rocket booster-like shell made from a nylon tent and a livestock hay feeder (all brand new); a projection inside this canopy shows an unknown body of water. “Hardscrabb gle” skims over named places—Slab City, Drop City, Ogallala Aquifer—yet it is devoid of characters: its landscape shots and maps are armatures instead. In a back corner lean three full sheets of insulation, ready to extend the gray bulletin board that already covers one gallery wall. The gritty reality is that the idealism of the frontiersman, the free spirit, is necessary to, yet necessarily excludes him from, the society he protects and makes possible. John Wayne’s character in Liberty Valence, just like in The Searchers (1956), saves the frontier family, yet is not allowed to join it. Bailey couples the bitterness of John Ford’s longing for an impossible West with the similarly groomed outsider romance practiced by Smithson. There, the lack of convention is the convention; the artist chafes against self-imposed strictures, yearns for what they imagine were freer days.