General Motors opened its Lordstown plant in 1966. Built on Ohio farmland purchased a decade earlier, the facility assembled Chevy’s full-sized vehicles, democratized luxury items with names to match: Impala, Bel Air, Caprice. In 1971 production at Lordstown—one of GM’s most technically advanced facilities—was shifted to the compact Chevy Vega. Redundancies, layoffs, and technologically enabled speed-ups followed: when employees were requested to turn out 100 vehicles per shift rather than the average of 55, workers sabotaged cars coming off the line and went on strike.

In 2019 the last Chevy Cruze rolled off the line and the plant was permanently closed. Or, more precisely, it was “unallocated.” “People keep saying, ‘I feel sorry for you. Your plant closed,’” recounted David Green, president of United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 1112. “It ain’t closed, it’s ‘unallocated.’ What the hell does that even mean?”1 Green, of course, was speaking for effect. He knew what “allocated” meant in substance: any language in the national agreement protecting GM employees in the case of “closed” or “idled” plants doesn’t apply to a plant that is “unallocated.”

Photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier documented the last nine months of Lordstown’s operations. An exhibition of her works, “The Last Cruze,” was held at The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago between September and December 2019. The photographs were mounted on a succession of orange metal frames meant to resemble the assembly line in the plant. This newly published book pairs Frazier’s portraits with the testimony of workers, union officials, and their family members; installation views; essays by writer Coco Fusco, art historian Benjamin J. Young, co-editors and curators Karsten Lund and Solveig Øvstebø, and sociologist Werner Lange; and interviews with Marxist geographer David Harvey, US Senator Sherrod Brown, and the playwright Lynn Nottage.

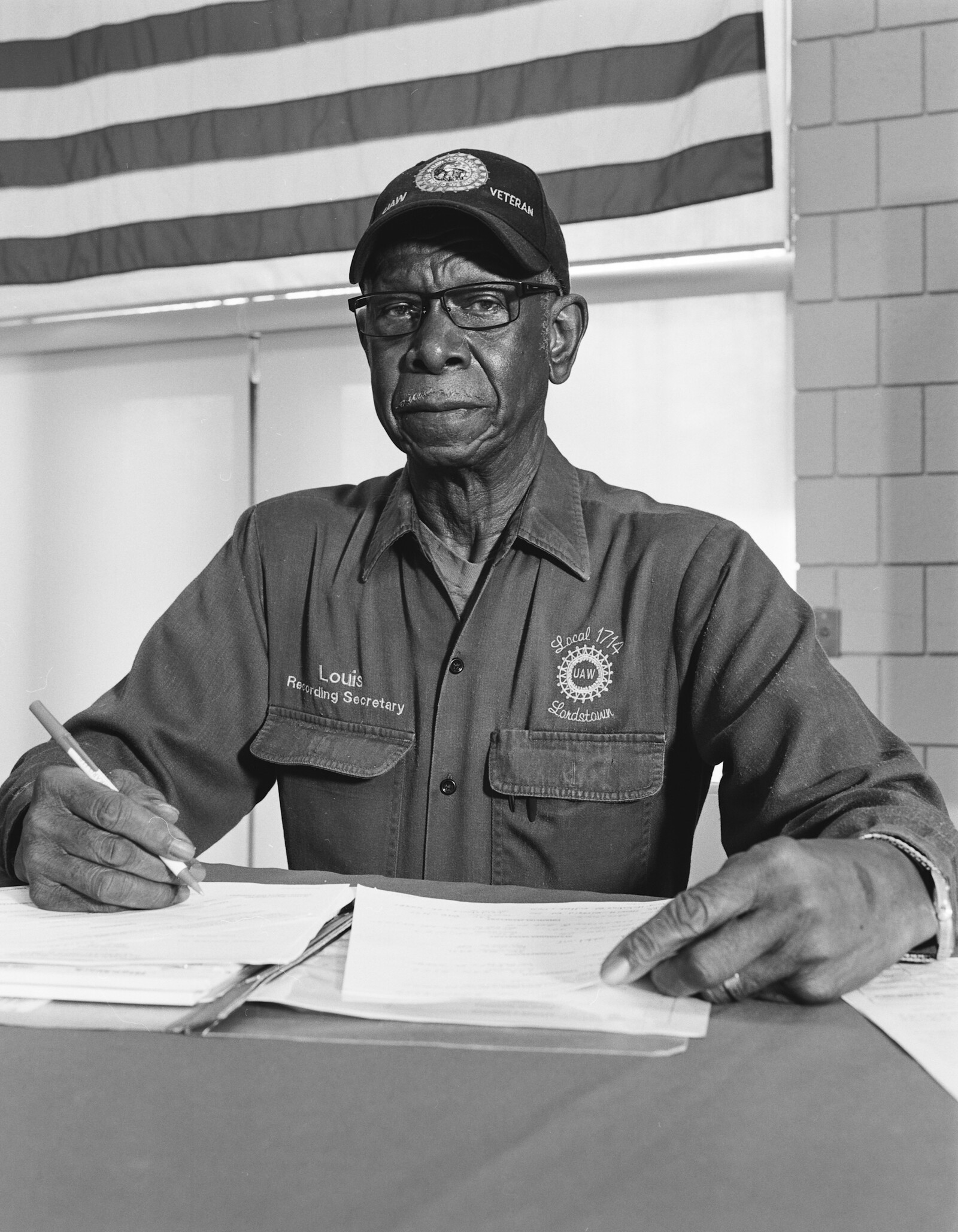

A significant number of the photographs are portraits, ones not marked by any dramatic or obvious formal break with a recognizable, even commercial, tradition of portraiture. Formally posed, in the vein of studio portraiture or older painterly traditions, the people portrayed here are clearly conscious of the camera, and actively involved in their own representation. While some touching moments appear unplanned, there is no realist conceit here: Frazier remains present and acknowledged by her sitters. The images are meticulously composed: as Frazier explains in a conversation with David Green, in certain interiors she was shooting with a very low shutter speed, requiring her collaborators to deliberately hold still.

The settings—often private and informal—underscore Frazier’s dependence on their invitation; those photographs taken inside the plant reject fantasies of alternately heroic and mechanically oppressed workers as workers in the tradition of Lewis Hine, and break, too, with the naturalism of the following generation of socially engaged photographers such as Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans. Familiar images of pickets and protests are few, and this protest imagery appears in ghostly projections onto the bodies of employees as often as in standalone images: the focus of this important project is more intimate. The cruelty of job loss, as Werner Lange points out in his essay here, lies in the fact that humans are social animals and cannot live on bread alone. Work, because it is a social relationship, is not, like capital, fungible. A plant closure is the implosion of a local economy and the shuttering of a space of collective work, social life, and purposeful activity. In this context there is no such thing as the individual and the family; there is only society.

Portraits of workers are tricky territory—both individual workers and the industrial working class have been instrumentalized by the very forces that have caused the sharp downward mobility of rust-belt cities. Nostalgia for manufacturing jobs is a crucial component of racist false populism. Furthermore, photography’s relationship to such decline is widely acknowledged as fetishistic and exploitative: a means of allowing well-heeled tourists to get a moral thrill from witnessing. The critical contributions to the catalog occasionally fall into this trap. Young suggests that Frazier’s installation is intended to insert the viewer into the factory by translating the compression of time on the assembly line into the compression of space for the viewer. But I don’t think that we, the readers, are the point of this book.

Whatever the viewer’s experience, the larger narrative that unfolds here makes clear that these individuals and families were supported, like these photographic images, by the assembly line; that their relationships to one another were organized in part by the factory itself; and that this organization of life through work—through the assembly line in particular—is not necessarily dehumanizing. The chassis and frame of the last Cruze were surreptitiously signed by UAW members and the signatures captured by an iPhone owned by Keith Burke, a sales and leasing specialist. That production is a social rather than a mechanical or economic relationship becomes tragically clear when the machine stops. Of the many ideas conveyed by Frazier’s interviews with plant employees and their families, one of the most striking is the unravelling of the social fabric that follows massive changes in productive activity. What the photographs show is the solidity and many intimacies of lives built over time in a particular place. What the project shows is that capitalism is incompatible with even the most modest stability.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, “The End of the Line,“ New York Times (May 1, 2019). https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/05/01/magazine/lordstown-general-motors-plant.html