I am not working, so I’m working out. Crunch and plank, back and forth. I do it next to my desk, on the ragged carpet brought back from Morocco decades ago, immersed in the most familiar of interior landscapes.

When I was in elementary school, an unspeakable fear of going blind (ommetaphobia; suggested treatment: hypnotherapy) made me secretly walk around my room at night, eyes wide shut, just to rote-learn every inch of its perimeter. Now, there’s an irony in using this domiciliary setting for exercise. On the wall above my desk there are black cats stretching, bending, and arching their backs, stencil-sprayed there by an artist friend, Riccardo Previdi, and inspired by Gatto Meo Romeo, a foam rubber toy designed by Bruno Munari in 1949 as a playful contortionist for young hands. They are a daily remainder of my sentimental education, based among other things on graffiti, punk comics, squatting, absurdist jokes, yoga, and modernist Milanese design.

In Berlin, I think it was the mid-2000s, Riccardo introduced me to his friend and fellow artist Gernot Wieland. We’ve been in touch ever since and I intended to visit his exhibition at Salzburger Kunstverein, which opened in February. But now I can’t. The three films on show (Thievery and Songs, 2016; Ink in Milk, 2018; and Square, Circle, Square, 2020), which were projected there in their original analogue film format, are now accessible as videos through the institution’s website. I watch the films under the sardonic gaze of my black cats and laugh at their deadpan humor. When they move me, I curl up on the rug, glad to hide my feelings from other eyes. I’m mourning the loss of a much-loved member of my family. Of course I miss white cubes, which abstract us from the vulnerability of our “daily persons,” in Brian O’Doherty’s term, and allow us to move around unnoticed, as “The Spectator” and “The Eye.” In his introduction to the 1986 edition of O’Doherty’s Inside the White Cube, art critic and poet Thomas McEvilley writes: “In classical modernist galleries, as in churches, one does not speak in a normal voice; one does not laugh, eat, drink, lie down, or sleep; one does not get ill, go mad, sing, dance, or make love.”1

But in housebound quarantine, people do all these things. This housetraining shapes our ways of seeing. John Berger compared visitors to an art gallery, “who stop in front of one painting and then move on to the next or the one after next,”2 to those at a zoo, proceeding from cage to cage, where subjects waver between lethargy and hyperactivity. (In the temporary absence of both galleries and zoos, I guess it’s not by chance that millions of viewers are obsessed by Tiger King on Netflix.) In an attempt to cope with intensive scrutiny within our own captivity, some of us even decorate our Zoom backgrounds with fake en-plein-air views. “Within limits, the animals are free, but both themselves and their spectators presume on their close confinement,” Berger writes. He cites the zoologist (and surrealist painter) Desmond Morris, who suggests that observing the unnatural behavior of caged animals may help humans understand the strain of living in consumer societies. Isolation and artificial environments affect the reactions of all creatures, who become “immunized to encounter, because nothing can any more occupy a central place in their attention.” When faces and images meet my gaze, now, through the screen, I struggle to sustain it: it’s as if they are visitors staring across my moat. Of course I miss my Responsive Eye.

Gernot’s films have plenty to do with animals, human and nonhuman: their domestication and their encounters. What makes them so compelling to me, at this moment, is their tactful supply of humor and imagination as strategies for survival, as well as their treatment of the psychopathologies of the everyday (anxiety, depression, grief) as part of everybody’s lives on the planet. They take in pain and process it. Small catharses ensue.

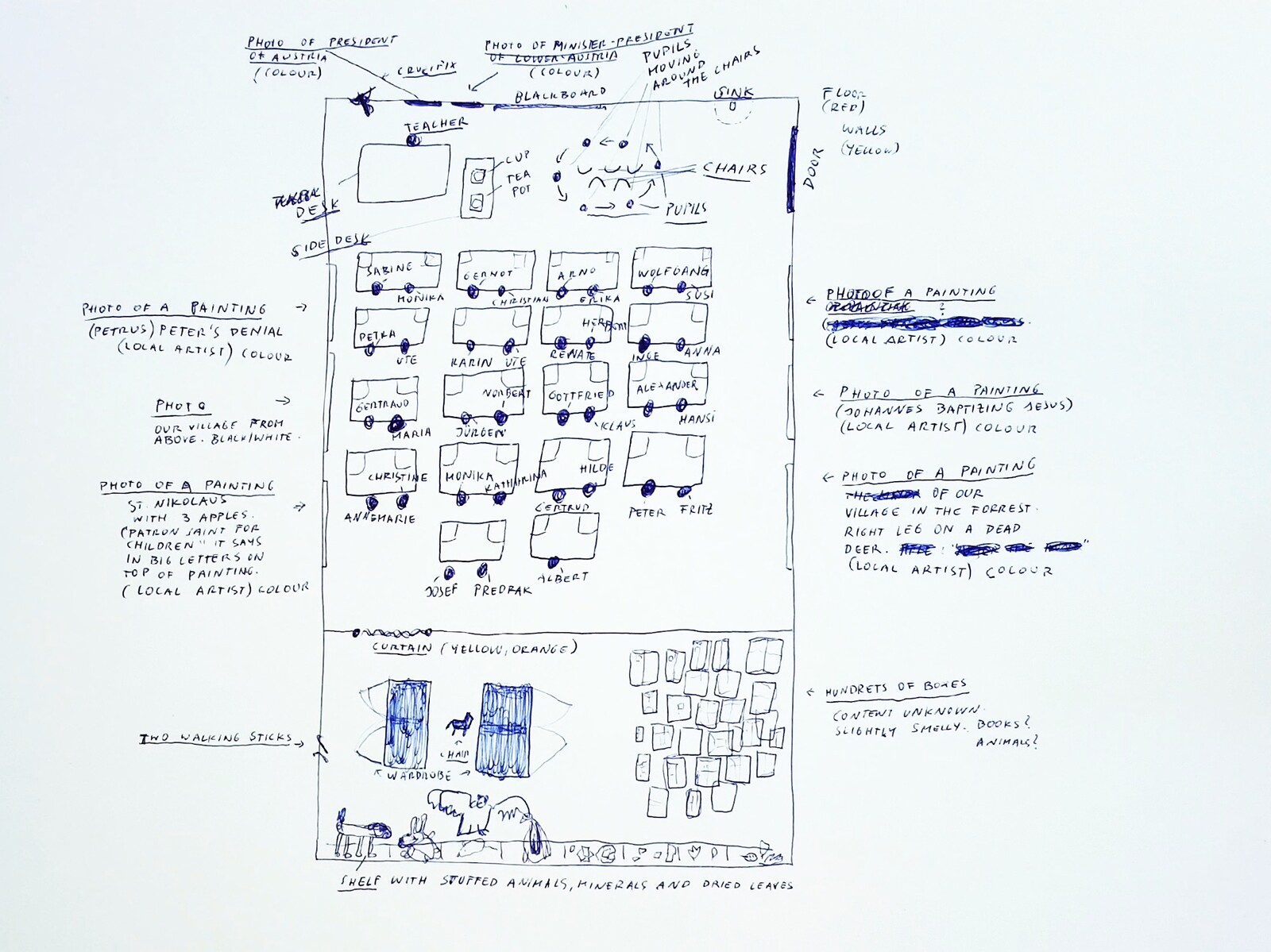

The stories are personal, narrated in voiceover by the artist himself and illustrated with simple media (pen and pencil drawings, watercolors, photos, plasticine animations, Super 8 films). Meticulously annotated maps reconstruct the backdrops of certain autobiographical episodes, often drawn from the narrator’s youth, but their childlike style makes it difficult to situate them either in the past or the present, as is common with dreams or memories. Likewise, they appear full of mistakes, exaggerations, fictional twists, and sentimental overtones.

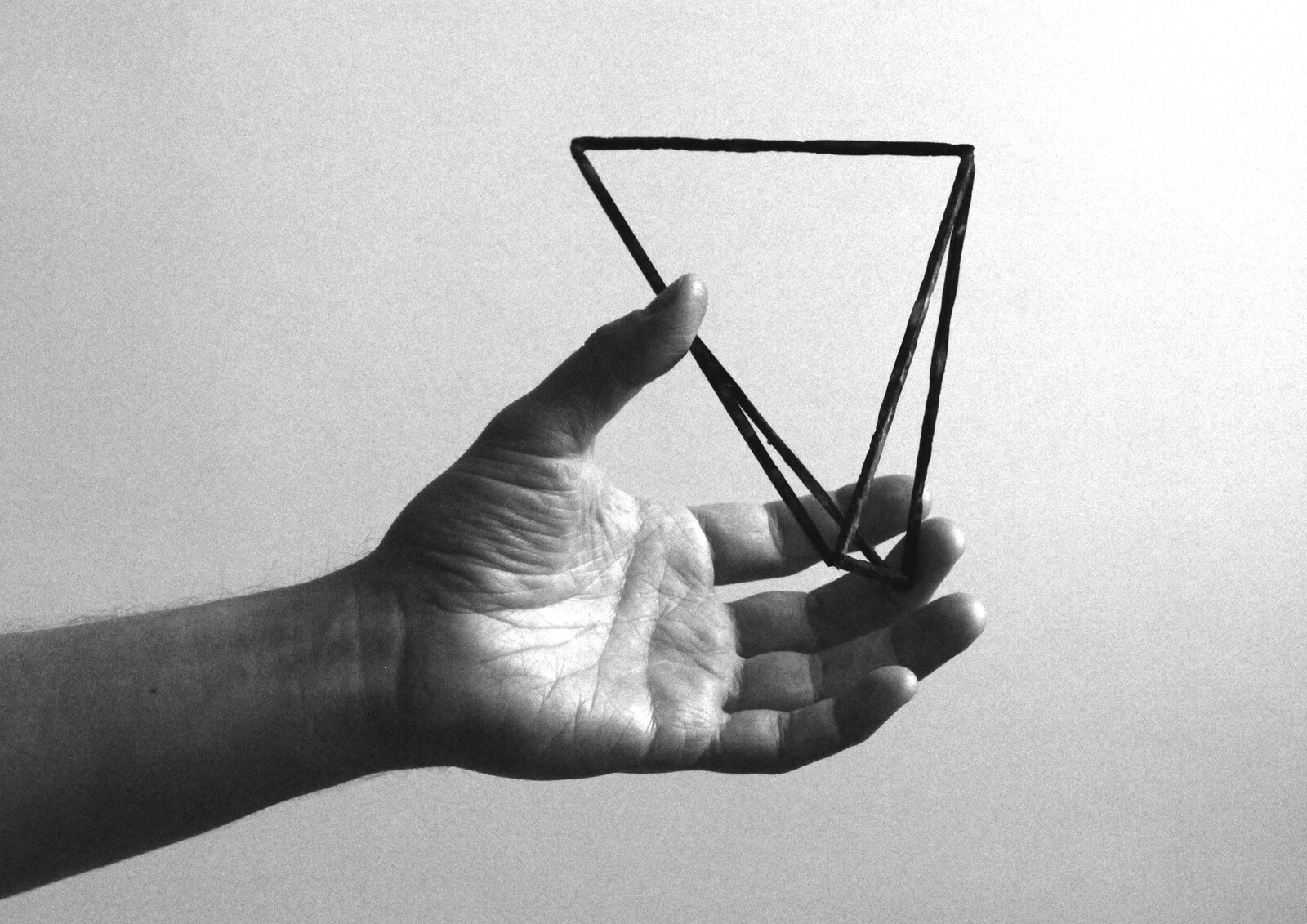

Ink in Milk (12 minutes 30 seconds) starts with the image of a dark liquid swirling in a sink (I’ve cleaned mine twice, today) while Gernot narrates the story of one of his best friends, a boy who came to school, aged eleven, wearing red lipstick, eyeshadow, and nail polish. The teacher enrolled him on her regular list of “losers,” who were forced to wrap around their heads a towel full of chalk powder from the blackboard and sit facing her cupboard, vulnerable to the gaze of others. “How we place our bodies in relation to each other is the start of politics,” Gernot says. The friend ends up in a psychiatric hospital; when visited, all he wants to do is walk up and down the stairs, as an exercise of freedom. (A friend recently recommended stair-climbing routines for cardiorespiratory fitness, I recall.) The narrator moves to another village, where a person known only as “uncle” convinces everybody to relieve their sorrows and fears by miming the geometric structure of the crystal associated with their psychic conditions. (Rudolf Steiner, who grew up in an Austrian village, felt during his childhood “that one must carry the knowledge of the spiritual world within oneself after the fashion of geometry.”)3 The practice becomes so absorbing that villagers stop working, cattle run away, and nature reconquers all dwellings.

A classroom also marked the beginning of the earlier lecture-performance Depression in Animals (2010–ongoing)4, demonstrating how human identity is constructed upon “the exclusion and control of the other—namely the animal.” One day, a sad schoolmate brings with him an equally sad German shepherd, and candidly reveals the dog’s fondness for sodomy during a biology class held by a taxidermist. The story unfolds along tragicomic lines, including the artist’s recollections of dealing with trauma through obsessive potato-print-making. “I remember sitting with this child psychiatrist in his room full of pictures of Flipper, Donald Duck, nice but imbecile-looking dogs, and he asked me, Gernot, how did you get here, why did you steal half a million of potatoes? And I remember it was not my voice but something in me said: because the zebra was so sad.”

Psychoanalysis is an obvious point of reference, as well as an obvious target for parody, with Sigmund Freud in pole position—it should be mentioned that Gernot is Austrian, although not Viennese, and entertains a conflicted relation with his culture of origin and Catholic upbringing. Thievery and Songs (22 minutes 40 seconds) departs from an excruciating therapy session and a dream, involving the cast of the fairy tale “The Town Musicians of Bremen” (a donkey, a dog, a cat, and a rooster), who lead the Occupy Wall Street anti-capitalist revolution, but wind up disbanding because they are unable to agree on who will have to stand above all others. The human fixation on anthropomorphizing everything, as well as on placing despotic Sapiens at the top of the natural ladder, seems ludicrous in a time of pandemic and climatic emergency. In the film, the idea of Vitruvian man as ideal measure of all things is wittily upended. With a nod to Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915), the narrator explains that “in order to understand the world or the many worlds” sometimes one must become animal, and clarifies that he is, in fact, a snail. He adds: “If you want to know how a snail’s life feels like in a human body, I can only tell you, it feels quite normal. […] I eat your food and pretend I share your taste.”

The third film, Square, Circle, Square, is silent and shot in 16 mm. It lasts only a couple of minutes, and wouldn’t be complete without its caption: “Wieland has collaborated for 12 years with an animal trainer who trained birds to fly in a circle or square.” We see black birds flying in the sky, alone or in small flocks; their trajectories remain open. Ancient ornithomancists used to see omens in these aerial maneuvers. Like the animals that roam freely across our empty streets, they seem to me to go simply where they want, without paying much attention to us. This morning, swallows returned to Milan. I think it’s a good sign.

Online viewing room

“Gernot Wieland” at Salzburger Kunstverein

Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (San Francisco: The Lapis Press, 1986), 10.

John Berger, “Why Look at Animals,” in Filipa Ramos (ed.), Animals: Documents of Contemporary Art (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2016), 68–69.

Rudolf Steiner, The Story of My Life (London: Anthroposophical Publishing Co., 1928), 11.

See gernotwieland.com.