The second Sharjah Architecture Triennial—featuring twenty-nine architects, artists, and designers across two main venues (the Al Qasimiyah School and Old Al Jubail Vegetable Market) and a handful of off-site locations—reckons with the cultural and ecological legacies of colonialism and modernity. The work shown does not, in the words of its curator, the Nigerian architect Tosin Oshinowo, simply acknowledge a wrong or apologize for the past. Instead, the contributions demonstrate modes of practice that build new worlds from the ruins of the present. Ideas of “impermanence” and “adaptability” here describe creative responses to conditions of scarcity that draw on ancestral ways of knowing and resourceful forms of making, and “beauty” as a celebration of survivance.

This triennial is in many ways a spiritual successor to Lesley Lokko’s international exhibition at the most recent Venice Architecture Biennale, “The Laboratory of the Future.” Beyond the handful of contributors to appear in both, in these exhibitions architecture is often a starting point, theme, and subject more than an end with pre-defined means. This approach liberates the exhibition from the representational conventions of architectural media (drawings, diagrams, models, maps, and photographs) in favor of immersive installations, sculptural works, films, and more that overcome the alienating “paradox” of exhibiting “something as large and complex as a building or a city […] as elusive as an architectural experience that unfolds in space and time.”1

A standout example is Sandra Poulson’s Dust as an Accidental Gift (all works 2023 unless otherwise stated), which reflects on dust as a marker of uneven colonial development by staging a scene from the Kikolo Market in Luanda, complete with shipping pallets, egg cartons, bottle crates, salted cod, Tang packets, jeans, pots and pans, dresses, and other ephemeral objects made in cardboard papier-mâché. Similarly, The Power of the ‘Invisibles’ by Yara Sharif and Nasser Golzari sets a series of material experiments developed in Gaza over the past number of years, which question the nature of architectural form under conditions of ongoing colonial violence and destruction, against the backdrop of an arresting CGI film that dives into the rubble, from which a “new skin” can emerge.

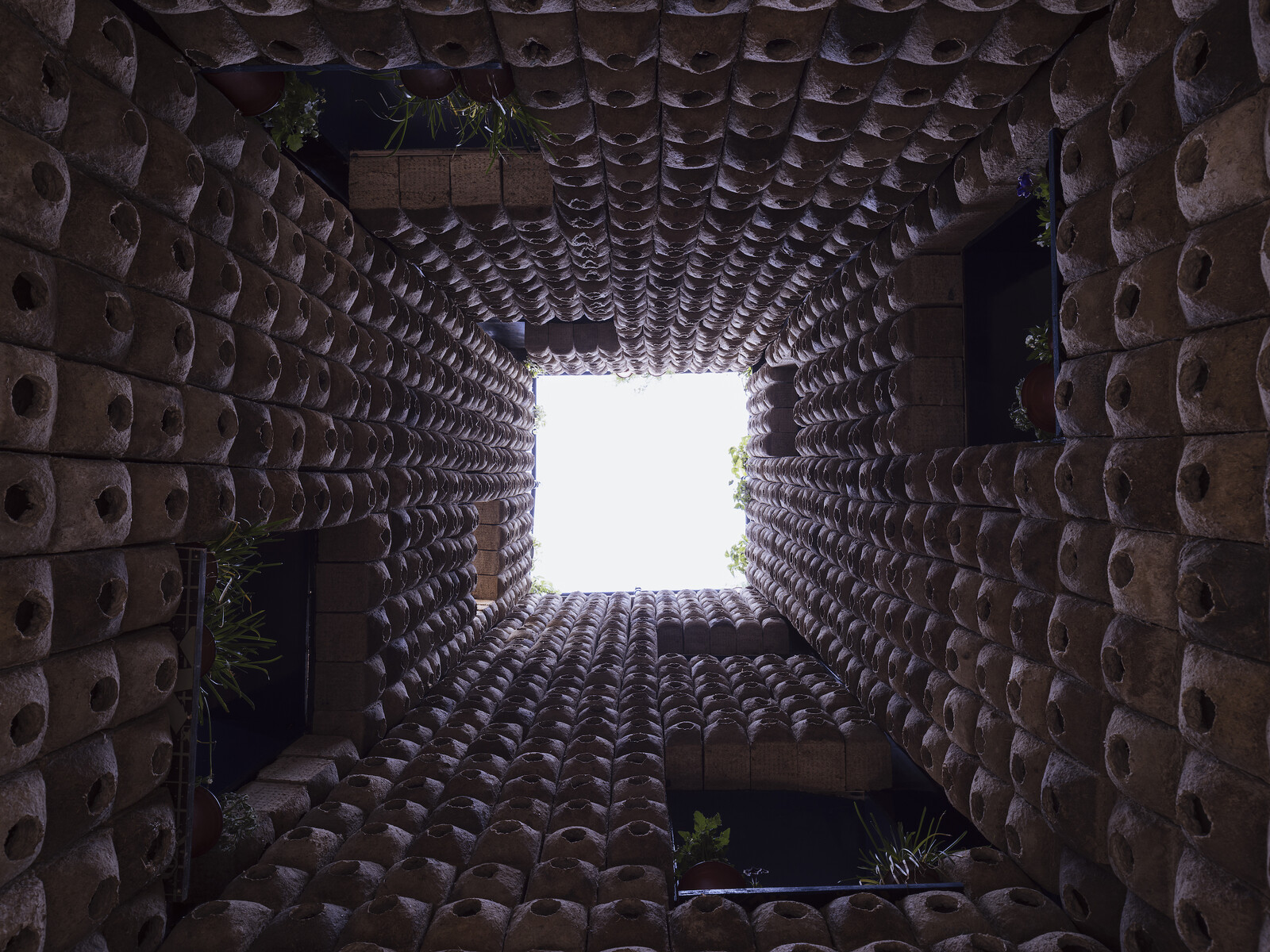

Scattered throughout the outdoor areas of the Al-Qasimiyah School are a number of 1:1-scale prototypes and installations, many of which demonstrate sustainable building methods with different materials such as rammed earth, mud, and car tires. They highlight an interesting tension between the curatorial theme of “impermanence” and the wider urban ambitions of the triennial, as well as the closely related Sharjah Biennial, both of which have been instrumental in fostering discussions around the value of modern heritage and urban space in the region.2 As part of Al Borde’s Raw Threshold, an ingenious shading system utilizing decommissioned wooden utility poles hovering above Cooking Sections’ contribution to the 2019 edition of the triennial, two sections of the site’s boundary wall were removed to create a new public path that cuts through the site, reorienting the institution outwards.

A number of off-site works attempt to facilitate discussions about the value of urban space in Sharjah and the region. At the Old Slaughterhouse, Cave_bureau’s Anthropocene Museum 9.0 leads visitors on a tour that meditates on how distanced contemporary urban society has come to slaughtering animals for food, connecting the facility with the ancient Al Faya cave in Sharjah that was used for animal sacrifice. Elsewhere, We Rest at the Bird’s Nest by Papa Omotayo and Eve Nnaji of MOE+AA/ADD-apt is a convivial space of hospitality for the existing more-than-human relations between workers, plants, birds, and machines in Sharjah’s evocatively named Industrial Area 5 district, and SUPER LIMBO by Limbo Accra drapes the entrance to the colossal, 65,000-square-meter unfinished Sharjah Mall to inspire new visions for unfinished buildings across the Global South.

This series of provocative engagements around ideas of (im)permanence, heritage, and value culminate about an hour outside of the city in Al Madam, in a village that was built as an attempt to sedentarize the nomadic Al Ketbi family during the early years of nation building, but was quickly taken over by the shifting sands of the desert and abandoned. Also intended to be subsumed by the dunes, DAAR – Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti have installed a new iteration of their Concrete Tent (first exhibited in 2015) which is dedicated as a space of mourning, with an audio recording reciting an incomplete list of the names and ages of Palestinian children killed in Gaza since Israel’s invasion on 7 October 2023.

“The Beauty of Impermanence” operates along a political horizon that places great emphasis on empowerment and solidarity over claims for emancipation and revolution. The exhibition is grounded in a common approach to spatial practice as it relates to the urgencies of this contemporary historical moment, including decolonization and decarbonization. Given this emphasis on approach, behind each contribution is a practice that could be said to operate according to a set of principles. While varied—and most often implicit—it would have been illuminating to see these principles included on the exhibition’s wall labels, alongside the materials and dimensions. This might have supported these works in their clear intention to intervene in the social and political fabric, while facilitating and strengthening a more explicit discussion about the shared ideological foundations on which such proposed futures are based.

Exhibiting Architecture: A Paradox? eds. Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen, Carson Chan, and David Andrew Tasman (New Haven: Yale School of Architecture, 2015) 9–10.

This is evident in the preservation of both main venues for the 2019 Triennial, the Sharjah Art Foundation’s recent restoration of the Kalba Ice Factory by 51-1 Arquitectos, and the enduring presence of a handful of works from the first edition at the Al Qasimiyah School and elsewhere in the city. Also of note is the publication Building Sharjah, eds. Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi and Todd Reisz (Basel: Birkhauser, 2021).