September 7–December 9, 2018

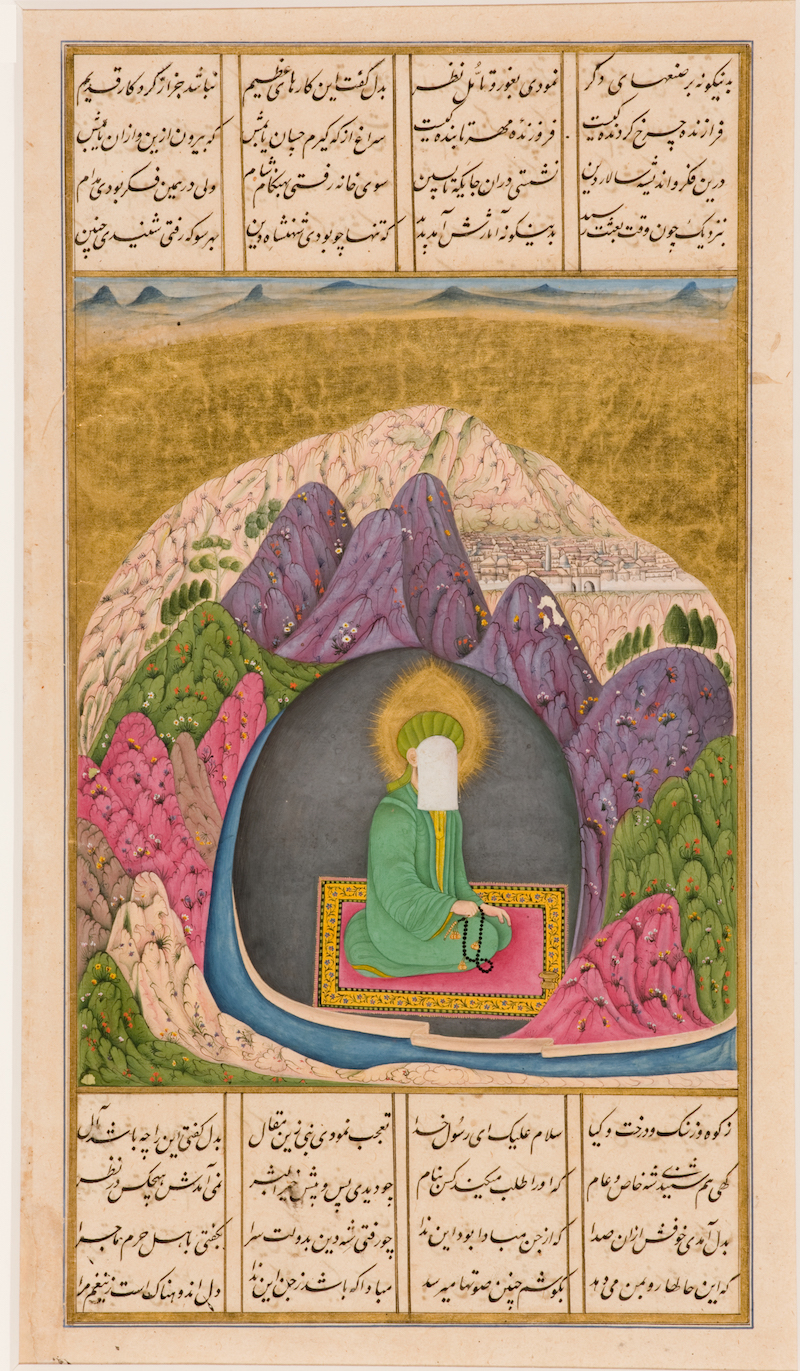

The source material for The Night Journey (2018), Haroon Mirza’s sound-based multimedia installation, is a miniature painting from the collection of the Asian Art Museum that is conspicuously absent from the final exhibition. The original painting, The night journey of the prophet Muhammad on the heavenly creature Buraq, created in India around 1800, depicts Muhammad on his journey from Mecca to Jerusalem with his face unveiled: a type of representation that has often been prohibited on the grounds that images of the Prophet can encourage idolatry. There is a roughly contemporaneous miniature painting of Muhammad included in Mirza’s exhibition: this one is, pointedly, veiled.

The theme of iconoclasm—the destruction of images—is thus woven into Mirza’s installation, which teases out from the perennial contentiousness of representing religious figures a more formal question, asking how the relationship between a subject and abstracted information extracted from it and converted into another form can be understood, whether as an appropriation, another type of depiction, or a form of censorship. In other words, iconoclasm is a starting point for the artist’s exploration around the limits of translation that transcend ideology into form.

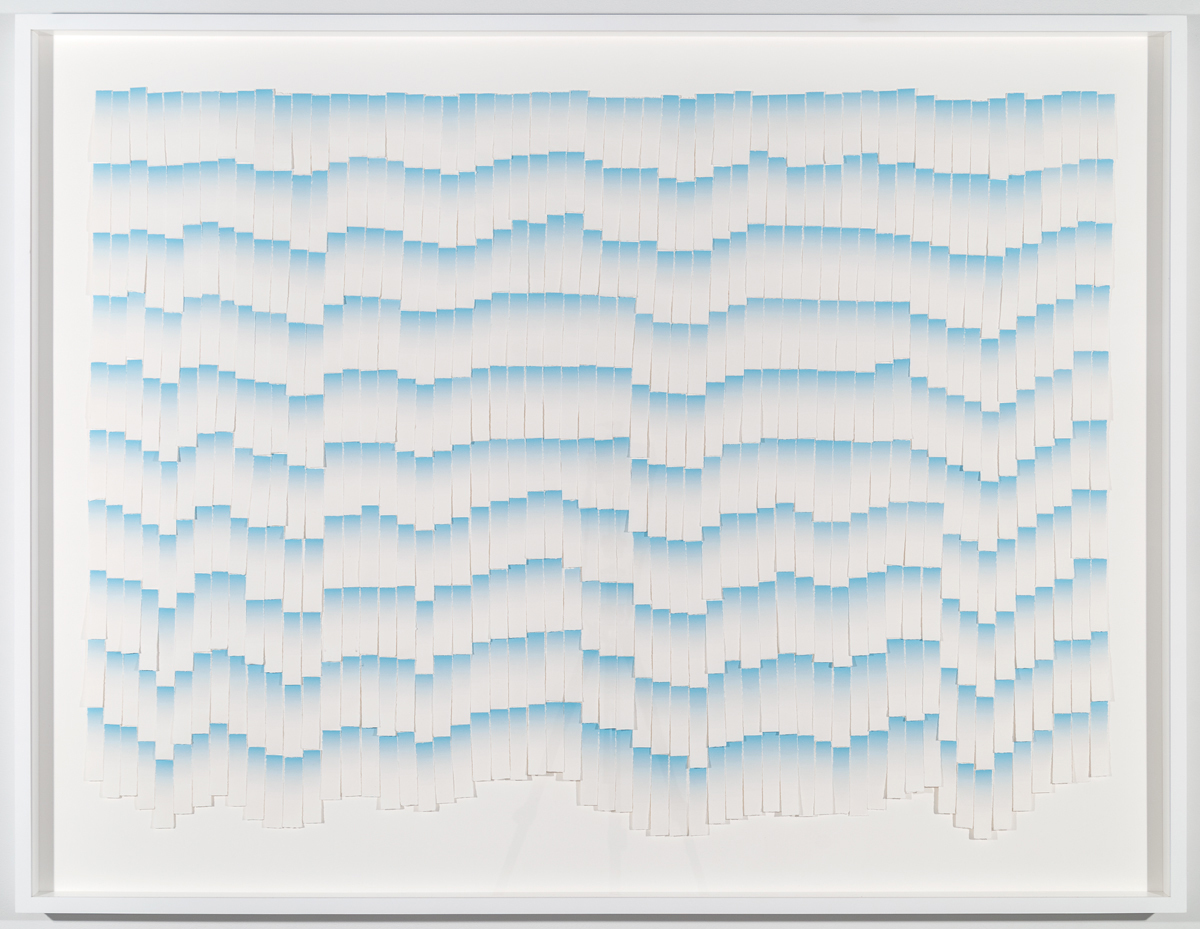

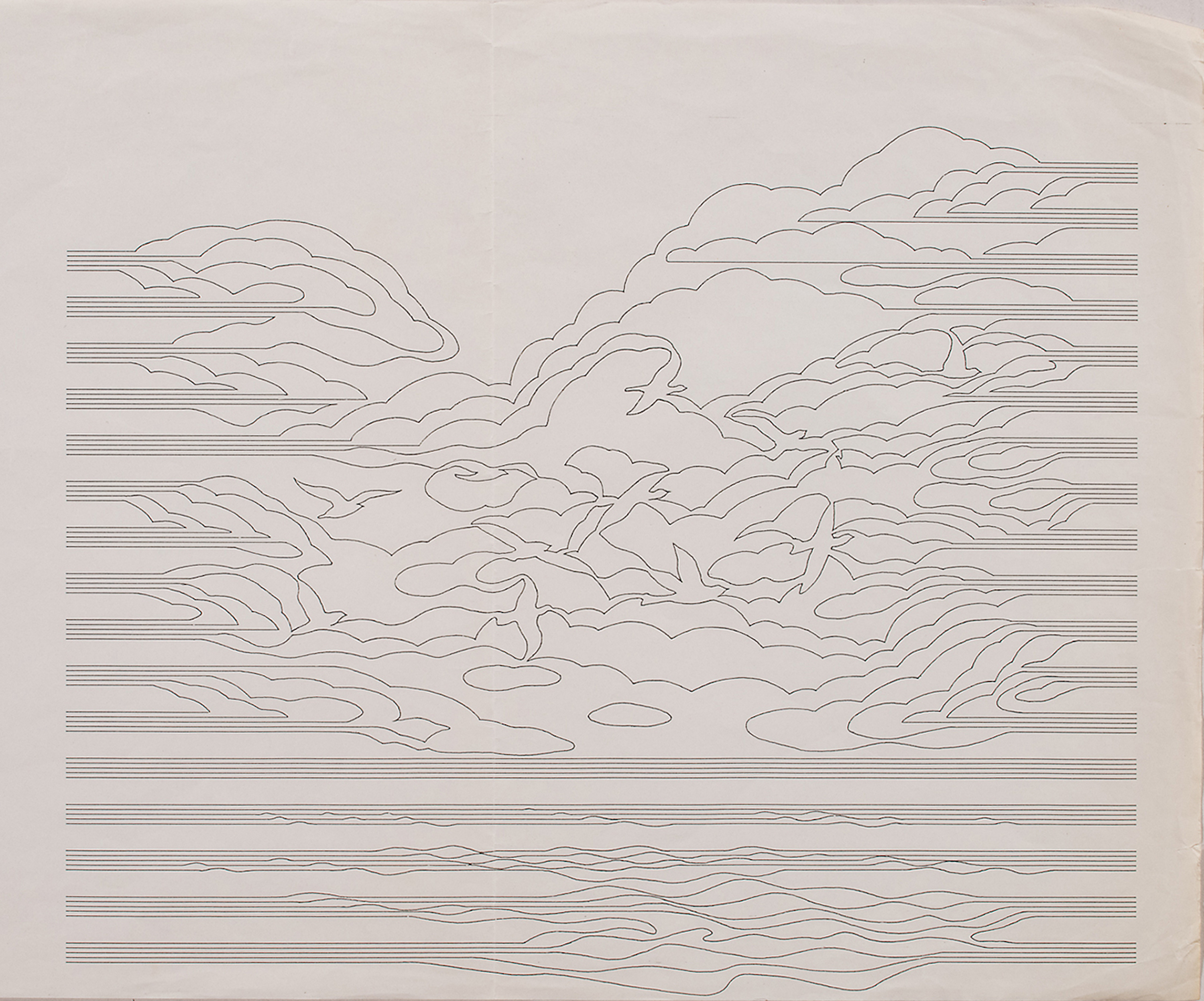

Mirza’s exhibition “The Night Journey” includes a pixelated inkjet printout of the c. 1800 painting, which suggests a digital image of The night journey of the prophet Muhammad was scanned and pixelated on a screen. The apparatus Mirza uses to do this rendering is a system called A C I D G E S T, created by the artist and first used in 2017 at the Pérez Art Museum Miami. Mirza has long worked with the interplay between light, sound, and electric currents in his installations; A C I D G E S T is the infrastructure for his first foray into translating between these mediums, a system in which electric currents travel through LED lights and speakers in coordination so that different colors on the diodes are activated by corresponding noise frequencies. The A C I D G E S T produces its pattern of currents using a predetermined score, which Mirza creates through abstracting and translating a source text or image. At the Pérez, the installation used the museum’s collections of concrete poetry as source material; here it codes visual information into aligned sound frequencies and then uses this code to create orchestrations of light and sound. The Score for A C I D G E S T (2017), the original source code based on the system’s inaugural installation at the Pérez, akin to a composer’s score, hangs in the exterior gallery of the show alongside the veiled painting and the pixelated printout of The night journey of the prophet Muhammad. These three objects indicate the two-step process of translation at work in the exhibition and suggest that the final transcription can be read as a substitute for the missing painting itself. A gentle pounding can be felt in this first room, which gives way to pure physical experience next.

Mirza’s media system fills the entire main room of the exhibition. A circle of large Marshall cabinet speakers face toward the middle of a thickly carpeted gallery, each speaker holding an LED light embedded in its acoustic fabric. The use of vintage speakers instead of loudspeakers immediately undermines any sense that Mirza’s translation is meant to be dispassionate or clinical; Marshall guitar cabinets are associated with big sounds from the 1970s, whether with larger-than-life performances of ’70s classic rock bands, who would have used a somewhat similar speaker setup, or home sound systems like those that someone Mirza’s age (he was born in 1977) would have grown up with. The throwback nature of the carpet and speaker setup, complete with the cables hanging from the ceiling and visible acoustic panels, create a space that feels oddly homey, personal, and comforting—especially striking given how much the sound and light contrast with this backdrop.

The sound of Mirza’s composition is loud in both volume and pitch, reverberating and buzzing with static, softened by the carpet but with vibrations designed to be felt by both ear and body. Musically, the first impression is a kind of avant-garde electronica using an oscillator being shifted very quickly, mixing classic industrial sounds, fuzzy transitions, and beeps reminiscent of old appliances. The LED lights in the speakers flash between colors just quickly enough to be recognized before shifting, creating an ever-changing visual spectrum that corresponds to the rhythmic changes in sound. At times choreographed light and sound is orchestral, symphonic, sometimes it sounds like noise; at moments it falls totally silent, as the light dims. It’s very difficult to tell how long the sound loop is, because it’s nearly impossible to discern which patterns of sound and light are real and which are merely created in the mind of the listener.

The careful home-like setup suggests the inevitable subjectivity and cultural baggage that is brought to such judgments. This humanizing of the experience also creates an anthropomorphism in the speakers themselves, welcoming in their warm mid-century physicality, and after a while give the impression that they are in conversation, responding to the sounds they make, like a choir singing in the round, or trying to tell you something. After even more time, their ecstatic noise becomes soothing: a phenomenology of the unfamiliar being translated by the body into terms we can make sense of.

Recognizing patterns and finding information in noise: the artist has created a physical analogue for reading a two-dimensional painting into a time-based experience. Mirza also suggests that—to return to the theme of iconoclasm—to break an image apart and replace it with sound and flashes of color is only to create another kind of mental, conceptualized rendition, whether real or imagined.