Oude Kerk is a fittingly resonant venue for Meredith Monk’s first—long overdue—retrospective in Europe. This massive thirteenth-century church houses highlights from a polymathic six-decade career that respond to (and echo in) its cavernous nave, with its vaulted wooden ceilings and looming pulpits, its high choir and chapels. To visitors (such as myself) who have only previously encountered Monk’s work via recordings, “Calling,” curated by Beatrix Ruf of the Hartwig Art Foundation, is a revelation. It brings together hypnotic video installations, sculptures, and archival material, yet the result is cohesive, not cacophonous. Each work has space to breathe. Together, they form a harmonious whole.

Several pieces have been revised or reimagined for this show. Amsterdam Archaeology (2023), an iteration of a work first shown in 1998 and the first viewers see upon entering, is one example: a red ziggurat for the display of objects donated by city residents and dipped in beeswax (or “Beuys wax,” as it risks being known in art contexts). These yellowish, translucent cauls point to the union, evident across this exhibition, of industrious and protective instincts. Monk has for decades sought the holistic union of art and healing.

Installations housed in freestanding (and judiciously soundproofed) rooms extend this cocoon-like quality, creating enclosed miniatures of operatic spectacles. ATLAS (1991/98), with its glowing atlas globe and toy-like sculptures of boats and cars, distils the sweeping, searching qualities of the titular opera—loosely based on the life of explorer Alexandra David-Néel—to the scale of a child’s bedroom. A child is also central to Quarry (1976/98); here, the dream of travel has darkened to a nightmare of isolation. A quilt and pillow on the floor indicates where Monk performed a bedridden girl surrounded by X-rays, rubble, floating white airplanes, an old radio through which the opera’s music plays, and footage of performers crawling over quarried stone evoking the ruins of World War II. One could call these Gesamtkunstwerks, in which visual art and music are synthesized into integrated, enveloping wholes. One indirect argument of “Calling,” however, is that sounds and images, voices and spaces, inner lives and historical contexts, were never separate to begin with.

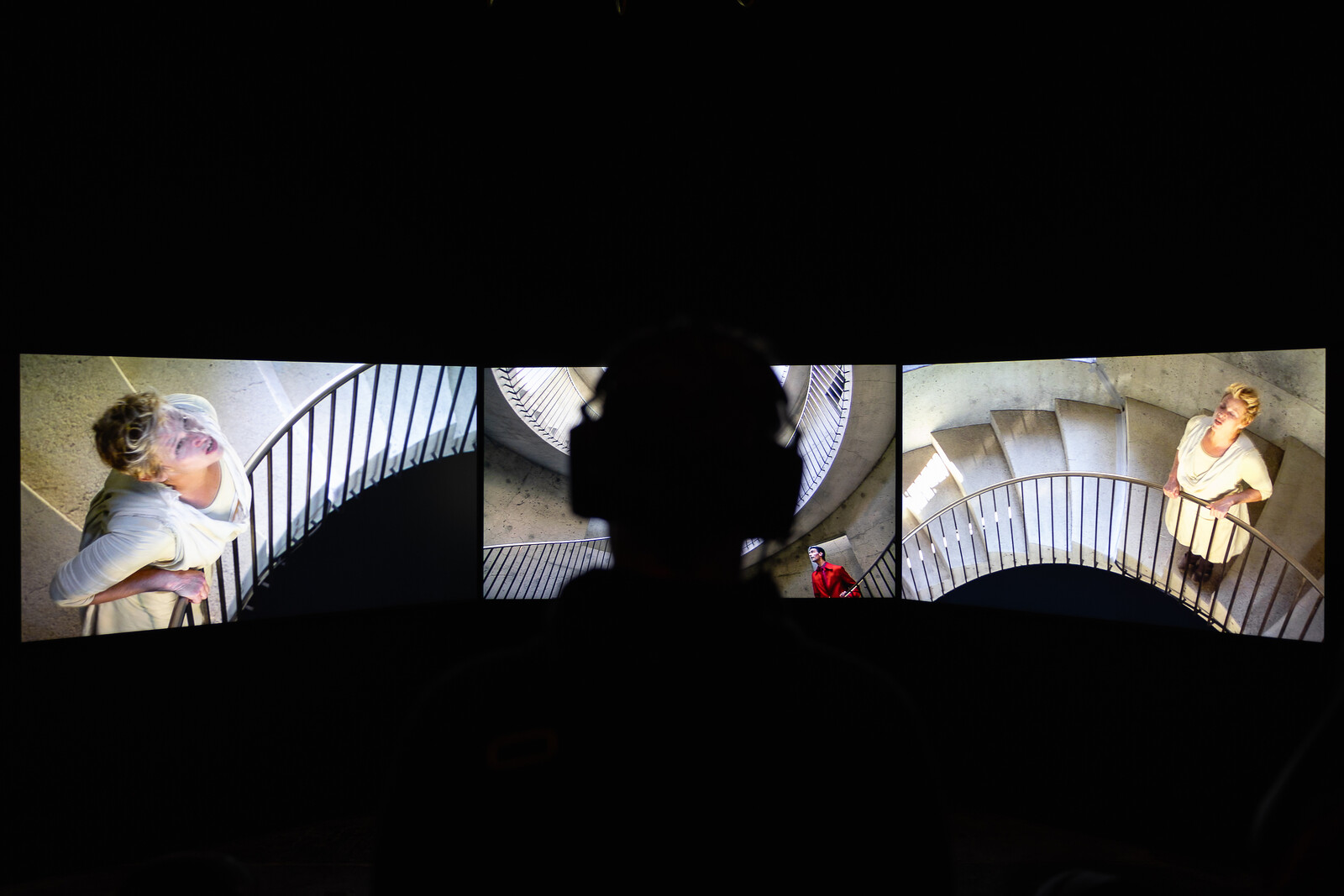

This extends to Monk’s site-specific performances and installations. In a chapel off the main space is Songs of Ascension Shrine (2023), a three-channel video installation based on documentation of a performance by Monk and an ensemble of musicians and singers in Ann Hamilton’s tower (2007) in Geyserville, California. This eighty-foot tower with its spiral staircase fills with sound, like a giant concrete throat. In the main space—the video installations play sequentially on large screens suspended from wooden beams—Rotation Shrine (2021) pairs black-and-white footage of people turning round and round, as though on rotating plinths, to densely layered chanting, the sound of which reverberates in a transept as a choir’s might. Hand Reflection and Hand Mandala (both 2018) combine images of flexing hands to clucks, clicks, and whistling exhalations that echo off the uneven floor, which is paved with tombstones.

As the monumental organ occupying the south wall illustrates, music is as integral to the building and its rituals as it has been to Monk’s career. First and foremost a composer, her principal instrument, and arguably her central subject, is the voice. Her “expanded vocal technique,” with its bird-like trills, plangent wails, leaping glissandos, and staccato laughter (to name a few skills in the repertoire), brings to singing a dynamism more typically associated with contemporary dance. In doing so, it reconciles grand themes—mortality, spirituality, micro- and macrocosms, the cyclical nature of time—with expression at an individual, human scale. Rooted in musical traditions both distinctly twentieth-century and considerably more ancient, her work as presented here feels remarkably fresh.

A hallmark of Monk’s technique is its rigor, here “expanded” to the scale of an exhibition. Visual motifs—hands, faces, the color red, bees, human skin, the surface of the sun, and various scales in between—recur throughout the show in ways that echo the rhythmic economy of her compositional practice. There are many voices here, yet hardly any spoken language. One senses it would get in the way: what ideas this show contains are to be felt as much as thought. With its titular resonances of vocation, communication, and mediation, “Calling” presents a body of work that is, by turns, as soothing as a lullaby and as arresting as a scream in the street. It is also, at points, very funny.

A pair of “rooms for listening and looking” contain monitors and iPads showing a trove of material, dating from the sixties to the present, including video works, performance documentation, music, interviews, and documentaries. Monk completists will have to visit dozens of times—either in Amsterdam or Munich’s Haus der Kunst, where a version of the show opens this month—if they wish to see it all: the iPads alone contain several hours of content. The risk of such archival plenitude is that the volume of available work can feel excessive to the point of redundancy. Yet alongside constituting a brute-force argument that Monk has been more than prolific enough to warrant a major retrospective in a contemporary art institution, this material is well worth exploring. There are gems here—the documentation of a 1977 performance of Quarry is a highlight—as well as context. In one documentary, Monk describes her work as exploring a “primal spectrum of emotions, emotions we don’t have words for,” which laughter helps express.

On the show’s opening night, inaugurating the live program that accompanies the exhibition, Monk performed with Katie Geissinger and Allison Sniffin, two longstanding members of her vocal ensemble, all three dressed in shades of crimson. Two songs in, however, and the audience hadn’t laughed at Monk’s solo acapellas, which combined virtuosic vocal work with gestures to Keatonesque physical comedy. Monk, who turns eighty-one this November, pointed this out. We were a “meditative” audience. She invited us to laugh.

The performers sang, played violin and keyboard, and moved over a softly lit stage in the middle of the church, surrounded by darkness into which voices rose and gave way to reverb. Geissinger and Sniffin have been members of Monk’s ensemble since the nineties, and these songs—“Gotham Lullaby,” “Memory Song,” and “Scared Song” among them—didn’t feel performed so much as lived through. Monk has said her music exists “between the bar lines and beyond the notes,” referring to the microtonal gradations between the notes on the western scale, but equally to something harder to define—that primal spectrum, perhaps.1 If it exists between the notes of the scale, it likely falls between the cracks of description. All of which is to say that I would have gladly sat through the concert again, long after its last echo faded.

Meredith Monk, “Process Notes,” liner notes, Atlas (ECM, 1993).