Beatrice Gibson’s first solo exhibition in Italy takes its title from Alice Notley’s column in the self-published 1990s New York zine Scarlet. In the column, Notley invited readers to transcribe their dreams, printing them alongside articles, poetry, and editorials about the AIDS crisis and the Gulf War, sharing with the Surrealists a feeling that dreams were both aesthetically striking and politically potent.

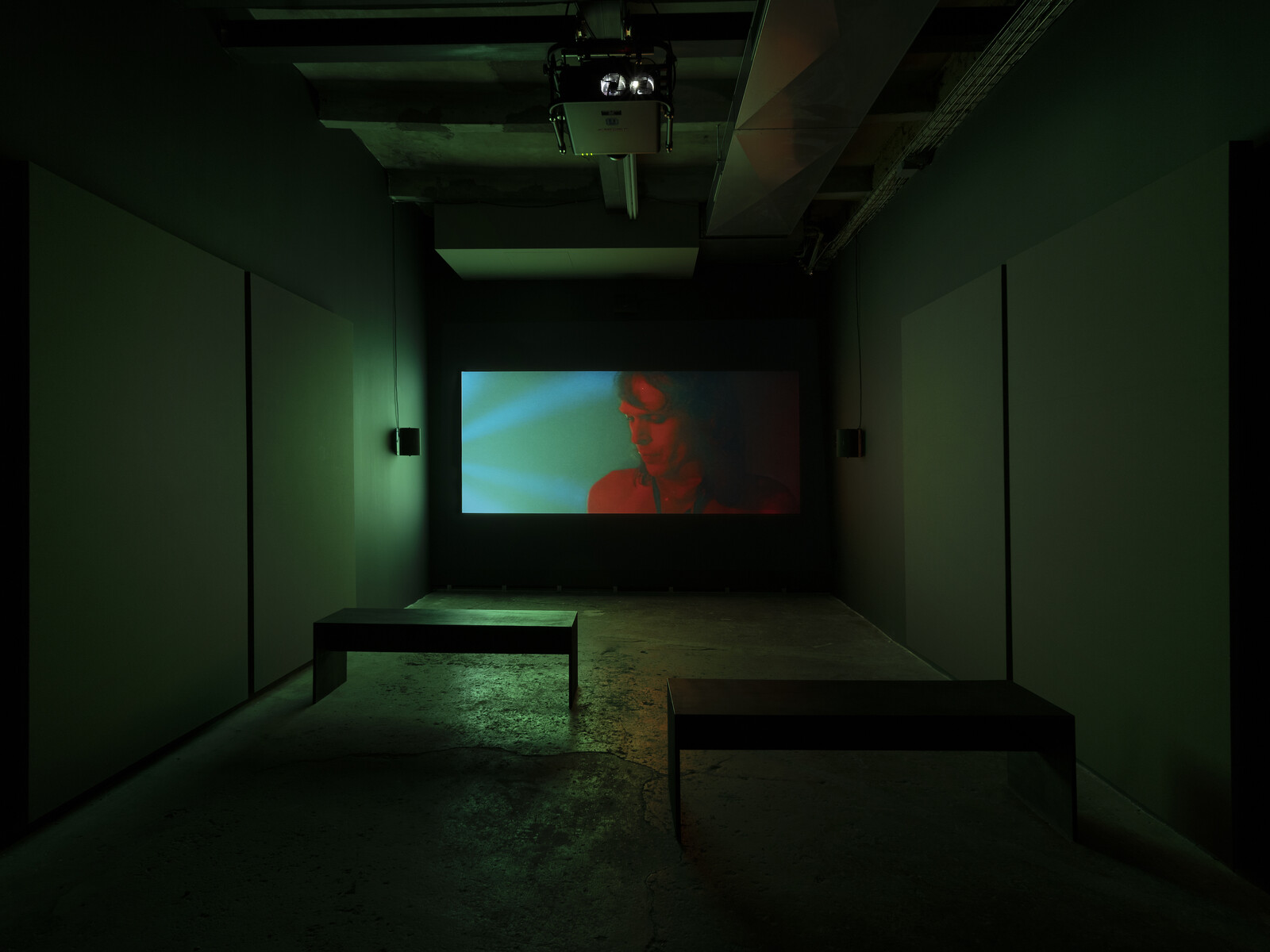

Gibson’s response to Notley’s work includes three films. Ordet’s main space is dominated by the newest, Dreaming Alcestis (2022), in which Euripides’ heroine inspires a portrayal of the process of dreaming, and how external stimuli, experienced by day or night, shape the unconscious imagination. In Dear Barbara, Bette, Nina—a four-minute work made in Palermo in 2020 and presented on a small monitor, with headphones, to one side of the room—Gibson reads from a phone a letter to three older women filmmakers over a shot of her hands at rest. Deux Sœurs Qui Ne Sont Pas Sœurs [Two Sisters Who Are Not Sisters] (2019), loosely adapted from a Gertrude Stein screenplay written in 1929, is shown on a large screen in its own room. It provides a collective portrait of Gibson’s influences, friends, and collaborators—including Notley herself—in a time of rising global fascism.

Addressed to Barbara Loden, Bette Gordon, and Nina Menkes, Deux Sœurs asks a complex question of feminist artists: How do you acknowledge the importance of transformative encounters with individual antecedents without reinforcing a Romantic conception of the genius, traditionally a man free enough of social bonds to dedicate himself to creativity? The film goes some way towards answering this question, refusing a linear narrative or central narrator in favor of a dream-like, communally minded procession of vignettes featuring Notley reading her poetry, filmmakers Ana Vaz and Basma Alsharif, artist Adam Christensen, and Diocouda Diaoune, who cared for Gibson’s first son. A pregnant woman’s monologue about bringing up a child across borders, with “four broken languages” between them, is striking: she is describing difficulties in communication within her own family, but hinting towards the way contemporary fascism stokes up resentment towards migrants who aren’t fluent in the native tongue. Queer/trans performer Christensen is shown singing and crying, but Gibson shows little reaction from anyone. This ellipsis creates space for reflection on how to convey emotions in a world in which every gesture is (over)familiar from mass media in a way that is actually able to make reactionary movements pause for reflection.

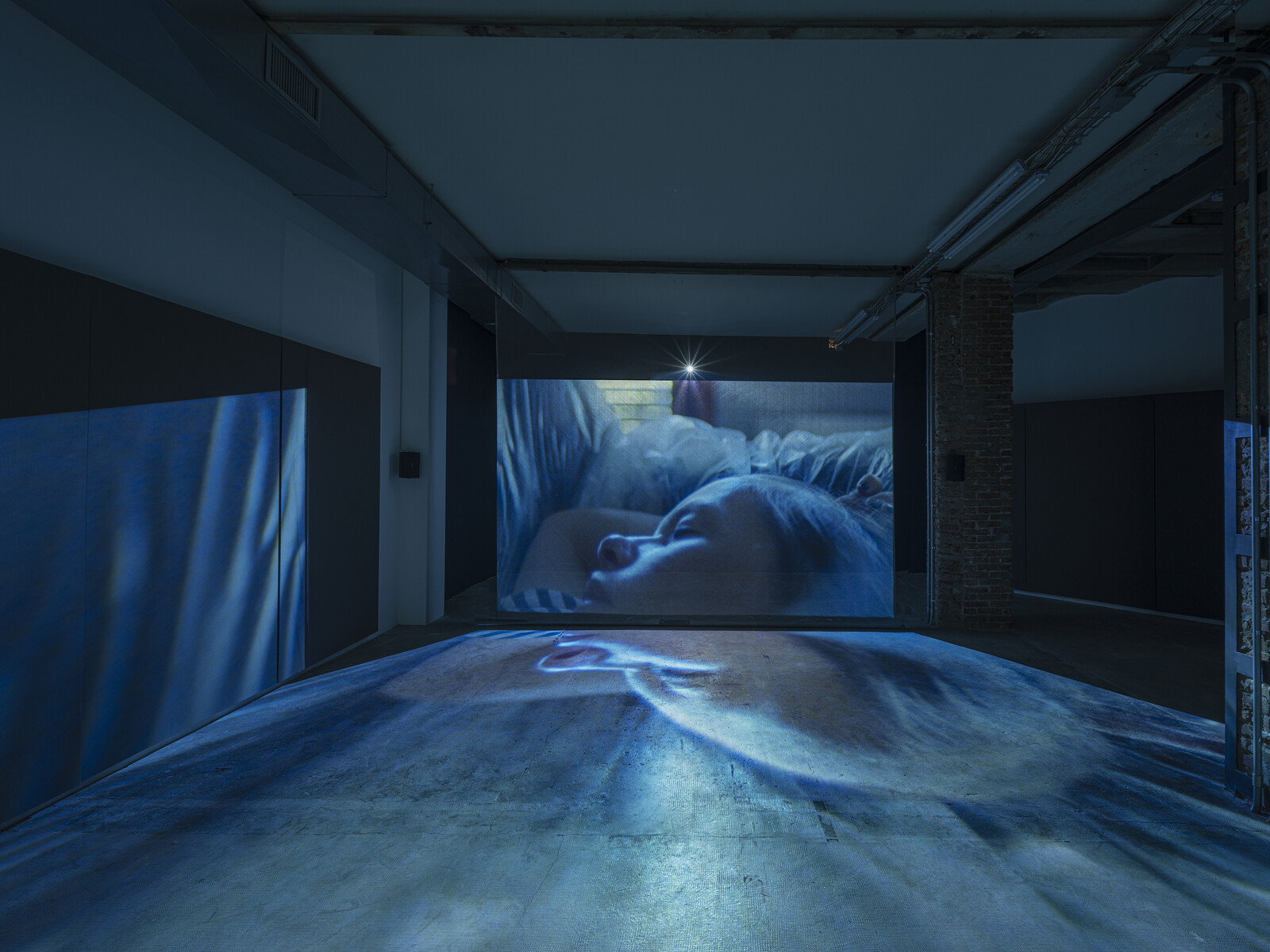

Dreaming Alcestis is slower, more abstract, and more meditative, again playing with movement from one country to another in an obliquely autobiographical way. It opens with a long shot of headlights fading into shots of Gibson, her partner Nick, and their children in a house full of unpacked boxes after their move to Palermo, the children playing (with each other and with a pet snake) as their parents sleep. The arrangement in the gallery is notable: Dreaming Alcestis dominates Ordet’s main space, and while the older films play on conventional screens, this film is back-projected through a transparent “Hologauze” screen, the image refracted on the floor as if it were a pool of water. The effect is impressive, duplicating and so defamiliarizing the otherwise commonplace images of sleep, giving them an enigmatic, permeable quality that might occur in a dream.

Gibson’s shots proceed with a slowness reminiscent of Béla Tarr or Andrei Tarkovsky, whilst the quadrophonic sound—in contrast with the other films—is played through wall-mounted speakers, separating it from the images and gesturing towards expanded cinema. With Italian voices talking distantly, rain on windows, drums, and traffic noises, there is the sense of the outside world continuing whilst the characters sleep and influencing their dreams—especially those of Gibson herself, in which she talks to Alcestis, the “heroine as subtraction” of Euripides’s play who sacrifices herself for her husband.

In the dream, Alcestis drives Gibson into the underworld on a motorcycle, with shots of headlights and engine noise opening and closing the work. A few captions momentarily cut into the carefully contained world that this looping creates, emphasizing that this in a film with sparse dialogue—and providing useful clarification in a work that, like many dreams, resists a singular or simplistic reading. In isolation, Dreaming Alcestis feels like a spectral presence, its thin construction of loosely synchronized elements creating a space for viewers to think about how their own dreams look, sound, and feel, and whether they say anything useful to us about ourselves or the world we live in, let alone whether they can inspire us to meaningfully change it.

Beatrice Gibson’s Dreaming Alcestis will be on view at the Museo Civico di Castelbuono, Palermo from April 15 through June 18, 2023.