Pioneering ecologist, science communicator, and marine biologist Rachel Carson found the rhythms of the ocean to be largely indifferent to the rhythms of humans. Coastal forms, she observed, merge and blend in variegated patterns with the ancient surf and with new life, ultimately with the sole agenda of the “earth becoming fluid as the sea itself.”1 Los Angeles–based artist David Horvitz’s solo exhibition at Belo Campo, a nonprofit space hosted by Galeria Francisco Fino in Lisbon, borrows its title from this ever-emerging movement as well as from Clarice Lispector’s 1973 novel Água Viva [Living Water].

Horvitz, like Carson, found in the compelling motion of large bodies of water the motivation to consider the passage of time, ignoring boundaries between identities, legal demarcations, and online or offline realities. Carson, whose work on the sea greatly inspired Horvitz—see Rachel Carson is My Hero (2016), his outdoor billboard near the bridge named after her in Pittsburgh—is quoted by the artist in his exhibition statement: “each of us carries in our veins a salty stream in which the elements sodium, potassium, and calcium are combined in almost the same proportions as in sea water. This is our inheritance from the day, untold millions of years ago.”2), 14.]

The sea has been a subject for many of Horvitz’s previous works. In Somewhere in Between the Jurisdiction of Time (2014), Horvitz travelled by boat to the longitude junction that divides the Californian and Alaskan time zones, where he collected 100 gallons of sea water which he then poured into 32 glass vessels and displayed in a gallery claiming it was an extension of Pacific Standard Time. In the two-channel video The Distance of a Day (2013), Horvitz simultaneously broadcasts on two smartphones a recording his mother had made of the sunset in the Pacific Ocean and his chronicle of the sunrise over the Laccadive Sea. Both works serve as reminders of the fluidity of the terms by which human existence is measured. As Lispector put it, “I want to possess the atoms of time. And to capture the present, forbidden by its very nature.”3), 3.]

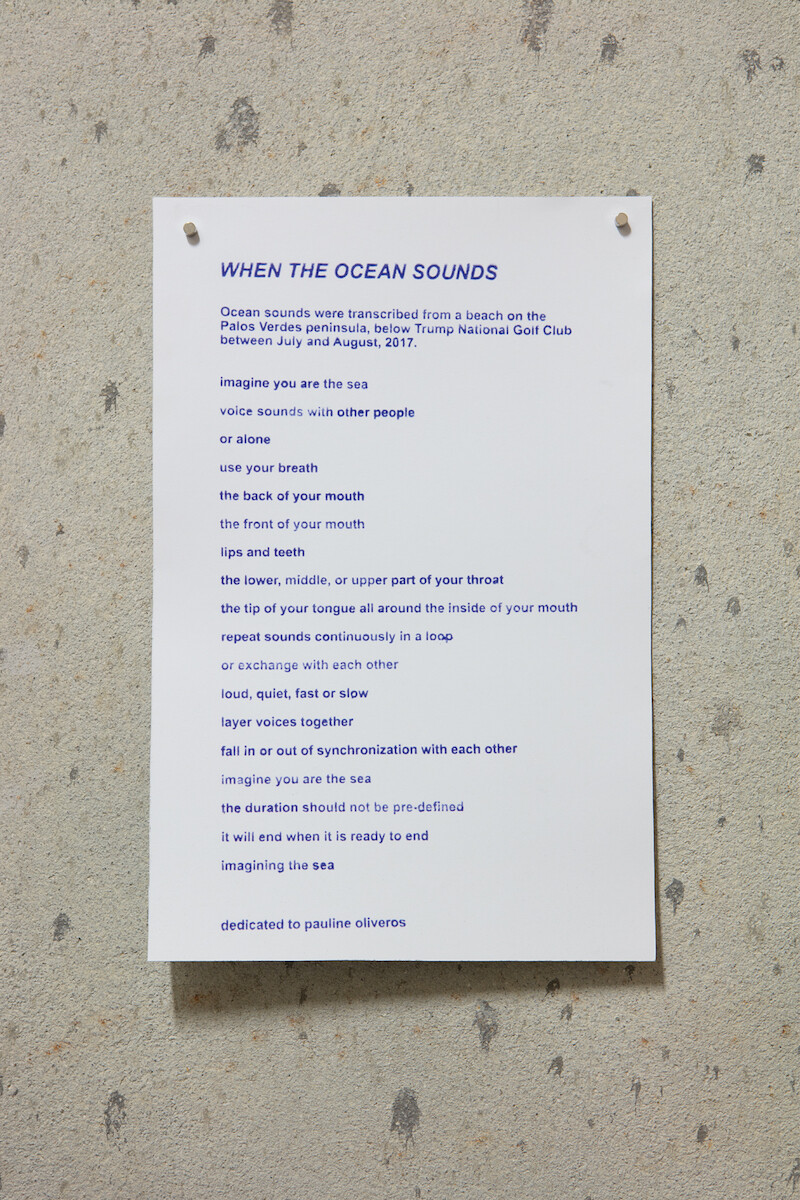

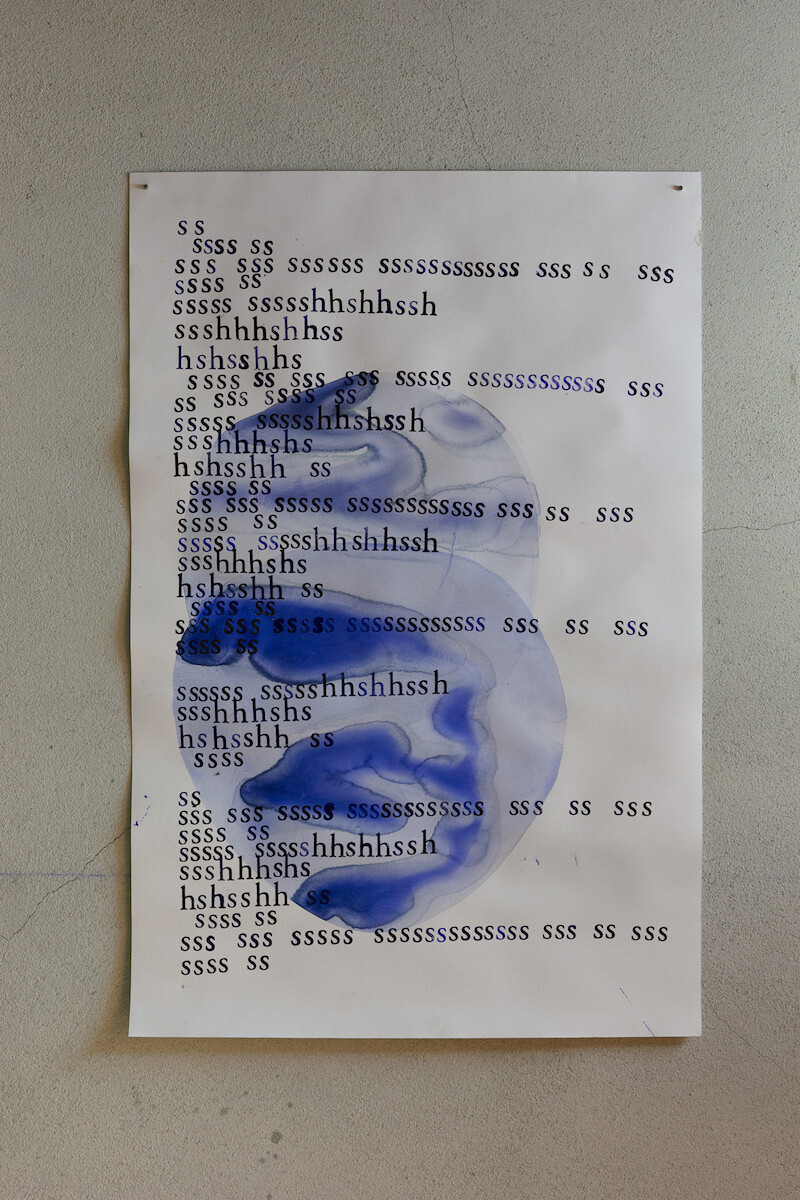

In the exhibition at Belo Campo, the artist expands on the temporal continuities between the body and the sea. When the Ocean Sounds (2018) is a set of 51 scores from a vocal performance for which he transcribed the sound of the waves breaking on a rocky cliff in Palos Verdes, California. Distributed digitally and as an exhibition handout, the notations are accompanied by a set of instructions that Horvitz reproduces with a stamp, dedicating it to musician Pauline Oliveros. The evening before the exhibition’s opening, the scores were performed live at Praia da Azarujinha, near Lisbon, creating a transoceanic dialogue, an embodied conversation between the Atlantic and Pacific. A photo from the event is hung at the entrance to the gallery, encouraging visitors to perform the scores with their own voices, relying on the acoustic properties of the concrete basement for an oceanic worldview.

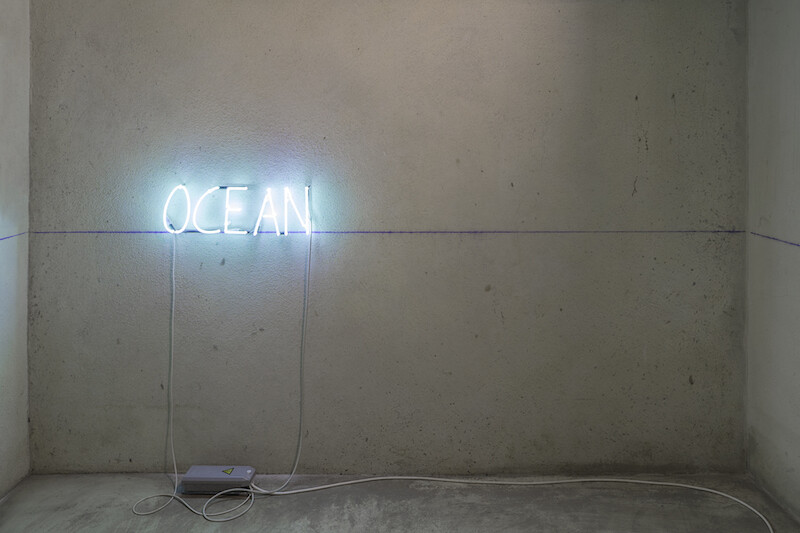

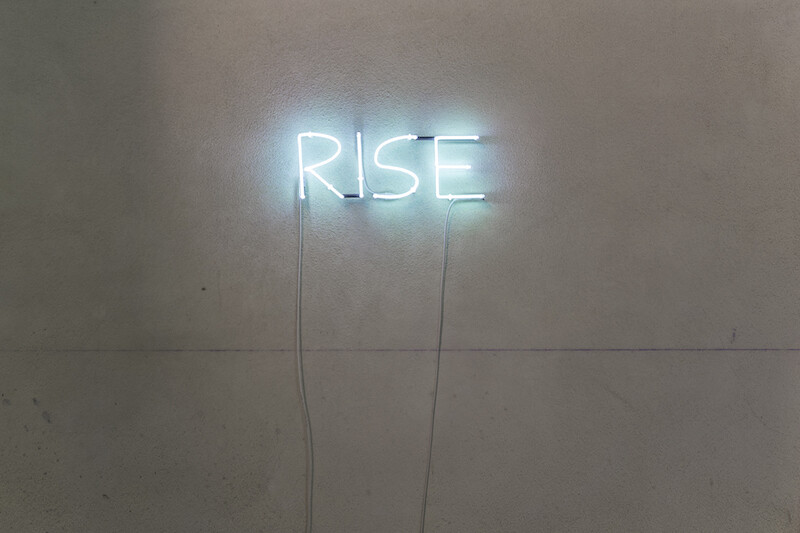

Across the space are nine watercolor scores from When the Ocean Sounds, made in ink, sea salt, and sea water on paper. The titles of the pieces reflect movement and time, as in Big Waves Coming from the Distance, Bubbles of the Surface of the Water, and Soft Wind on Water. The dampness of the underground space has caused the salt crystals to seep from the paper, creating a tinted blue imprint on the floor, which, in turn, challenges viewers to further consider the agency of the sea. Traversing the three small rooms, an undefined horizon marked by a construction line parsing the basement charts the position of four neon lights that together form the work’s title, Ocean Rise Night Fall (2018). It is a proposal for a tidal philosophy that connects the long vistas of history with the caveats of the present. From the early days of colonial expansion to the onset of exploitation of deep seabed mineral resources, this unsteady motion is a deliberate challenge to complacency.

Berlin-based artist Adrien Missika opened Belo Campo in October 2017 in the basement of Francisco Fino. The space hosts a program of solo presentations and is inspired by Horvitz’s Porcino, a spontaneous exhibition space operating out of ChertLüdde in Berlin whenever Horvitz visits the city. Missika, who is also building upon a previous collective curatorial experience in Lausanne, Galerie 1m3, describes Belo Campo as an epiphyte, an organism that grows on the surface of a plant and takes part in its nutrient cycles. Porcino, on the other hand, echoes the symbiotic lives of mycorrhizal mushrooms and the roots of vascular host plants. “Água Viva,” the third exhibition in Missika’s program, thus speaks to a genealogy of mutualism and affinity with both the gallery and the ocean, offering navigational roots and routes that extend long past the exhibition space.

Rachel Carson, The Edge of the Sea (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1955), 250.

Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 2003 [1950

Clarice Lispector, Água Viva (New York: New Directions, 2012 [1973