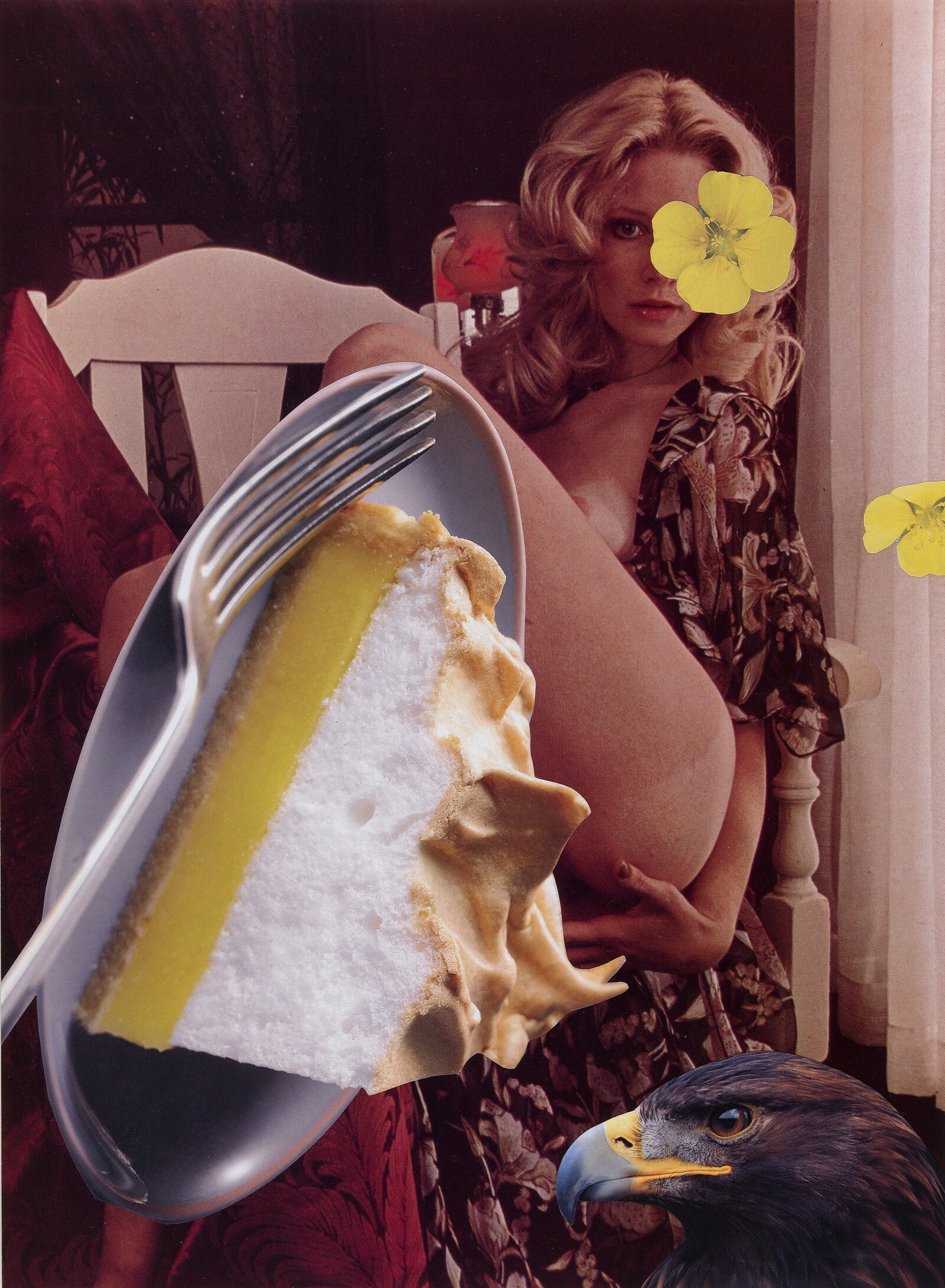

Let’s put it all up front: this exhibition is made up of 73 small collages, created between 2007 and 2019, each featuring one or two human bodies, accumulatively displaying 23 nipples (four of which have a more apparently male owner), four pudenda, and one (erect) penis. Some of these people lounge about in bygone versions of tastefully decorated interiors, looking confidently into the middle distance; a few in a state of semi-undress contort into various suggestive poses, giving the camera a dead-eyed stare; most of them, though, are preoccupied with the furniture and silverware being shoved into various orifices. In The Model 5 (2015), one woman looks on while another has a set of black enamel drawers angled between her legs, while in Magnitudes of Performance III (2012), a man looks ready to introduce an old hi-fi amplifier to his supine male partner. Most of the imagery for these collages seems to come, to start with, from porn magazines, and the rest from home décor catalogues. The excerpts from the latter—sofas, vases, and one well-placed tiger-striped lounge chair—act like a form of comedy censorship, blocking out the revelations and penetrations of the former to give the new images a more compelling, and at times more revealing, surface.

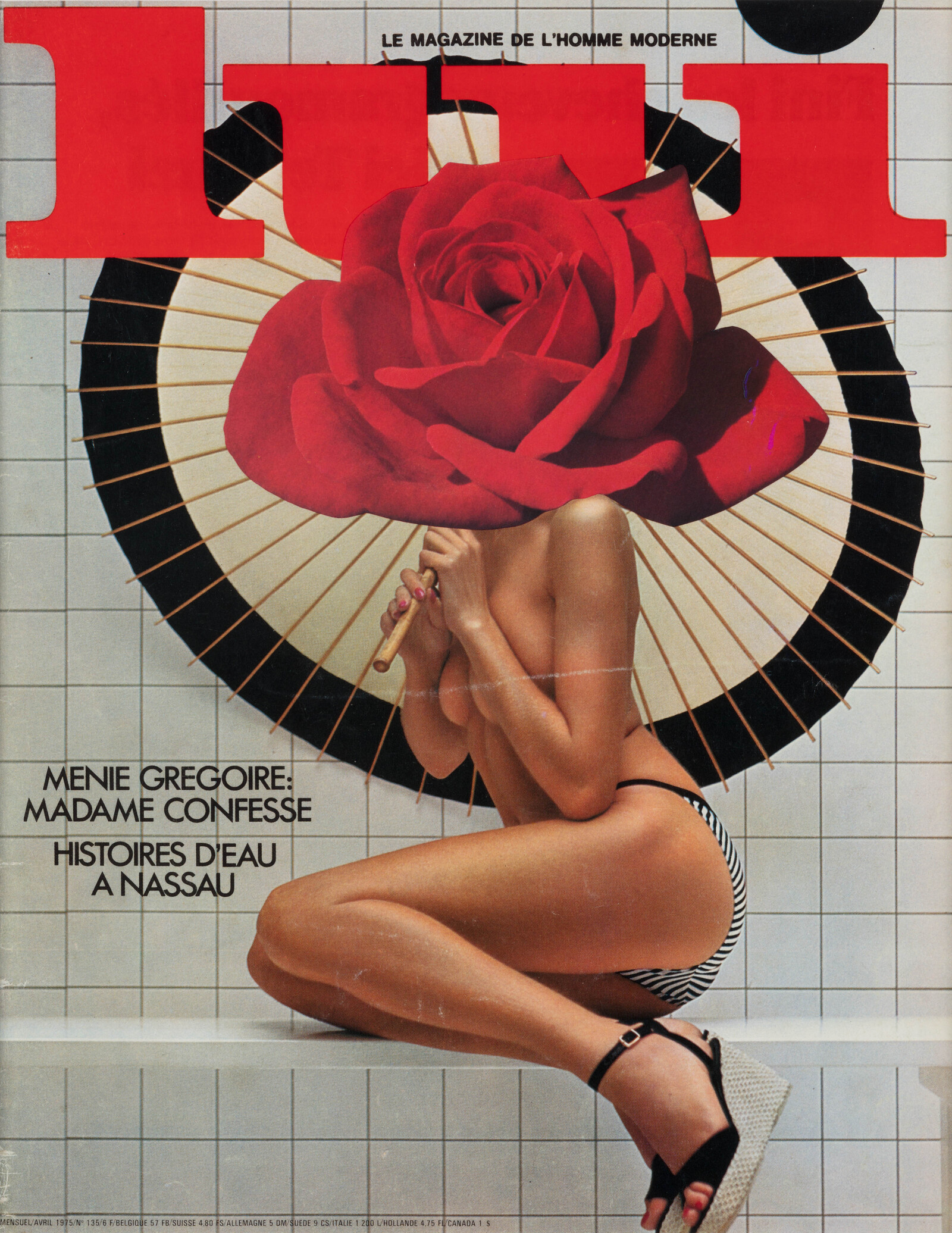

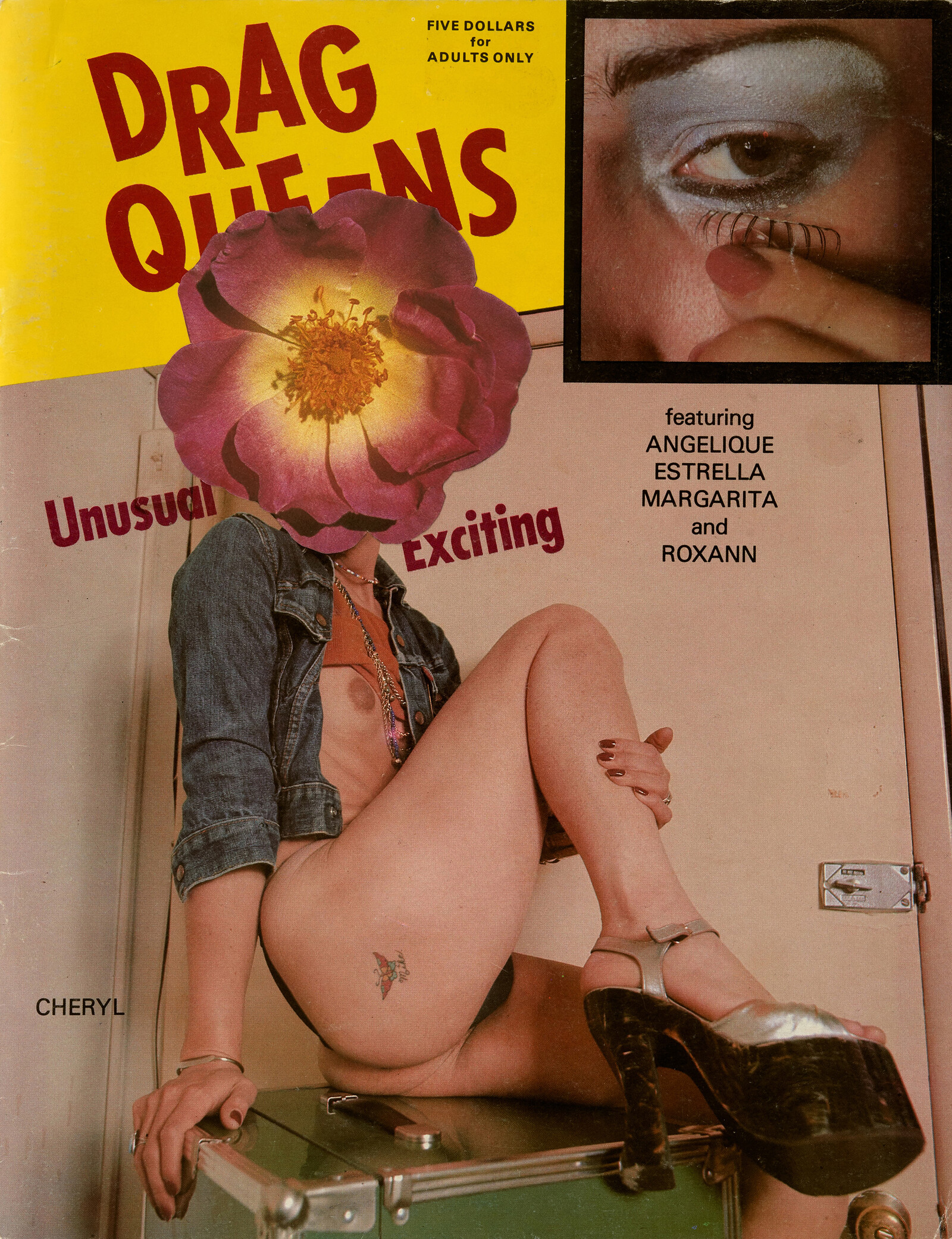

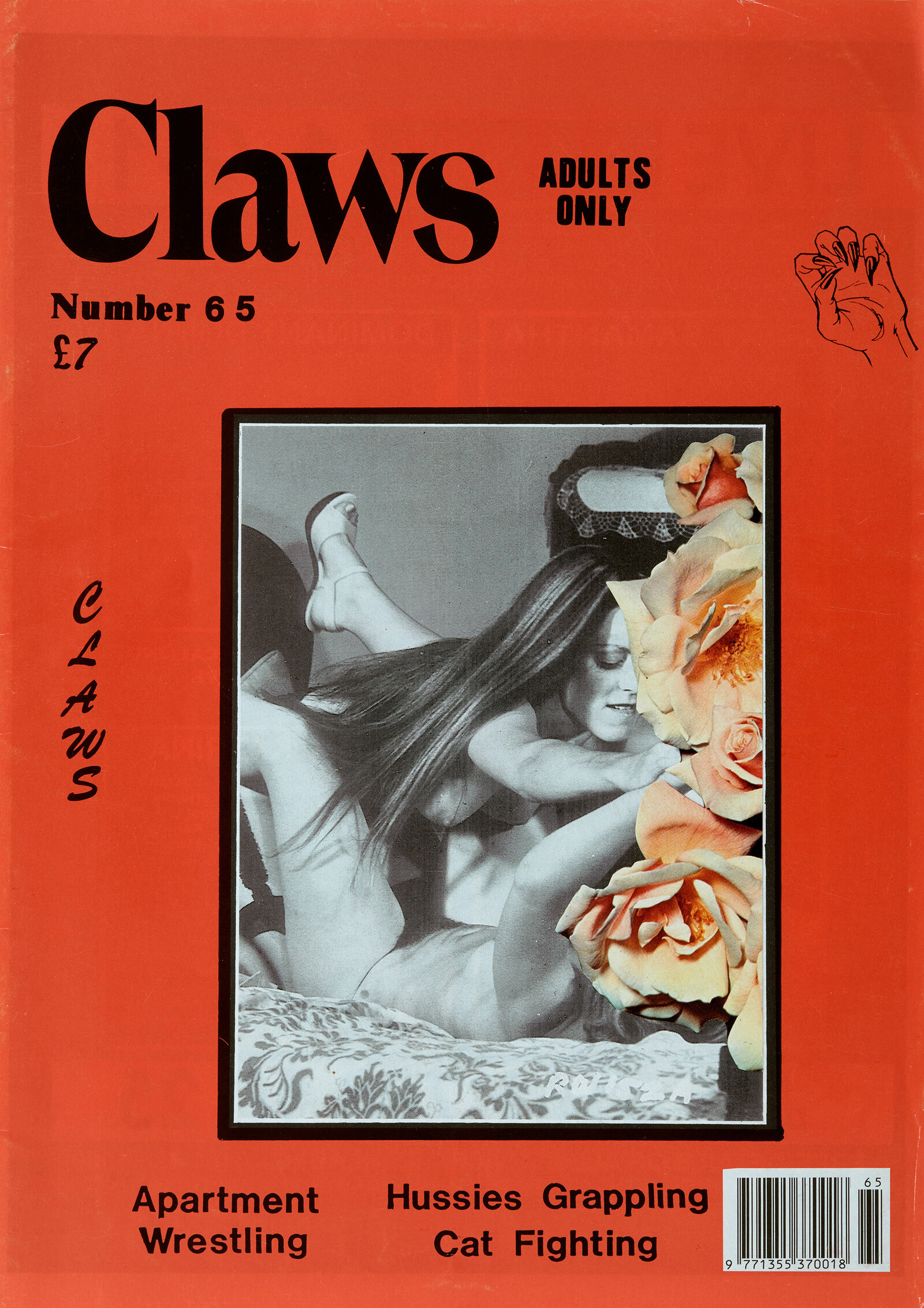

Linder is known as a stylish punk figure who has been making collage works since the late 1970s, often tweaking and riffing on media portrayals of the female form. Using exaggeration and juxtaposition to make explicit issues of domestication and objectification, in her photomontages heads become kitchen appliances, bodies are endowed with oversized, lipsticked mouths, and the spaces these commercialized chimera occupy are haunted by random floating bits of domestic desiderata—turntables, desks, silver dessert trays. “Ever Standing Apart From Everything” is more of the same. If anything, the exhibition is slightly more focused, with most images tweaked with a single intervention, like the rose blooming from the butt of a woman dressed as a schoolgirl on the cover of a faded copy of “Girls of the World” magazine in The Goddess who is secretive (2017), or the two-seater black leather sofa plonked over the face of the actor’s headshot in Vlady Relief (2017). Linder’s method—and aim—is consistent with the medium of collage since it was originated by Dadaist Hannah Höch just over a century ago: excerpting from mass, print-based media, the cutting and pasting of disparate sources was intended to disclose, or release, the subconscious specters lurking in the imagery. Here, the household goods covering up the hanky-panky going on suggest what the participants are really thinking about: having sex, while pondering what veneer to get the table in, or what bedside lamp would really suit the living room’s green walls. We’ll never be animals thoughtlessly rutting anymore: we eat, sleep, fuck commodity culture.

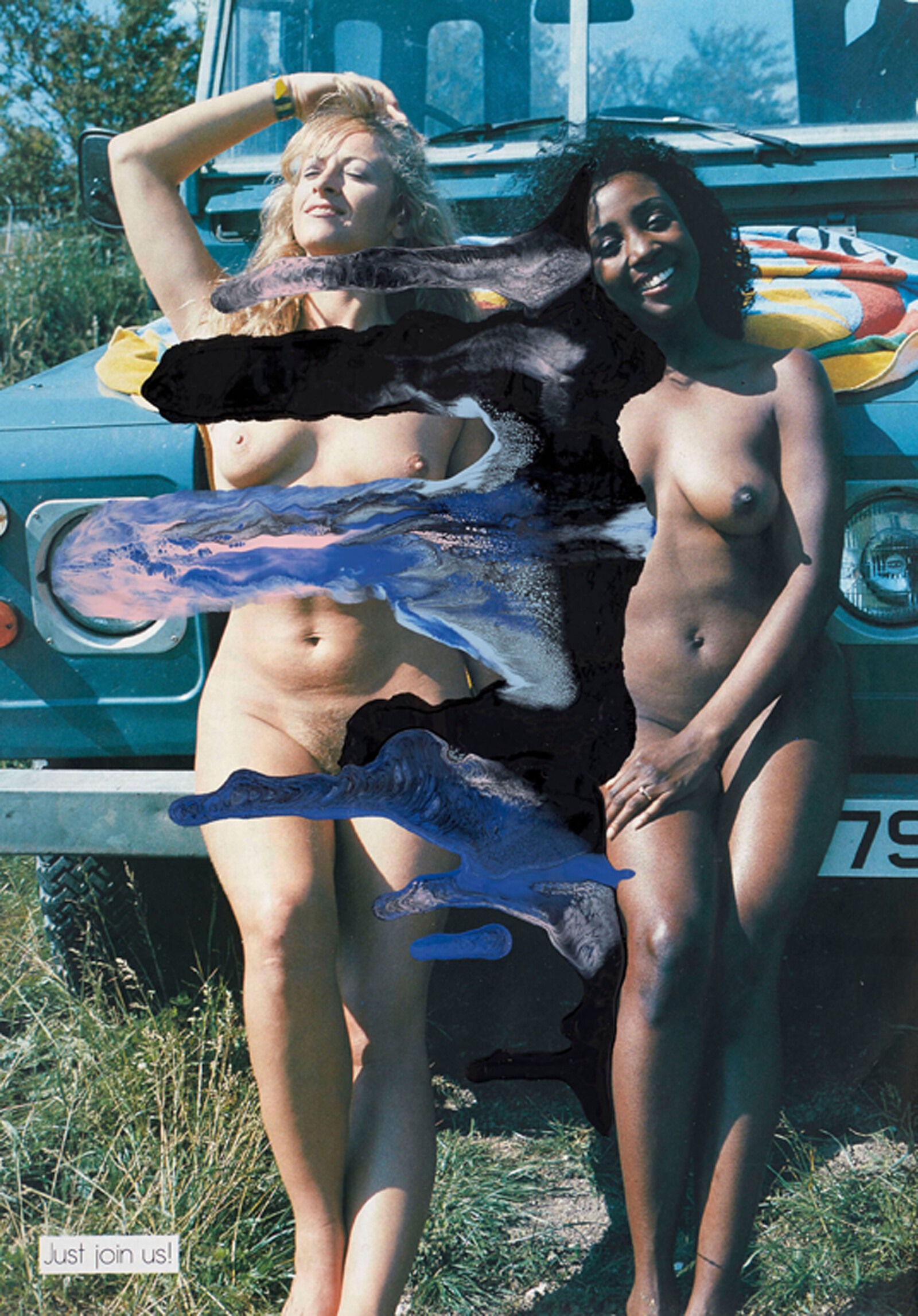

But this point, like some of Linder’s imagery, is fairly trite—itself a commodity that has been repackaged and hyper-spun continuously over the past few decades. The collage appealed to the punk aesthetic in the 1970s as an easy action with a bigger implication, ripping away and rearranging layers to reveal the rotting state of the status quo. Linder’s own artistic trajectory reflects that of British punk: appearing in zines, then creating the mass art form of album covers, to adorning the gallery walls of the national institutions that punk once sought to overthrow. (She hasn’t, thankfully, gone to that next step of punk-repeating-as-farce, of Johnny Rotten Country Life butter ads or those insurance ads where Iggy Pop argued with a puppet version of himself.) Probably one of the most profitable and picked over of subcultures, one part of punk’s legacy is that its supposed anger was directed for the most part at itself, the white middle class, and it turns out the unconscious it revealed was just a spoiled brat gagging for attention and money. These images are a send-up of the brat, though the brat’s probably too busy laughing all the way to bank to care. Only the “Superautomatism” series shown here suggests a different approach, putting multicolored smudges of paint onto pages seemingly from a 1980s nudist magazine: in Superautomatism XII (2015), a woman leans forward as if blowing a dandelion, with a swath of black, white, and gold paint stretching toward another woman standing nearby—like she’s blown a hole in the universe. The series carries the same metaphorical weight and humor as her usual MO, while managing to be less dogmatic and more suggestive.

The question of what impact these collages have on you might depend, I suspect, on whether you believe in the knee-jerk spark that punk always claimed to have. As a suburban kid raised on the watered-down pop punk of the 1990s, I guess I still do. Overstatement and obviousness is part of the point of Linder’s ongoing psycho-sexual imagery: the problems she has continually addressed have only cosmetically budged. But the content of each collage is in some ways interchangeable, and it is the sustained and focused intent of her work that is more powerful and instructive. Punk was supposedly about a template that anyone could use: here’s three chords, now form a band, etc. As figures like Linder, Viv Albertine, and Poly Styrene (RIP) have made clear, the only punk that really died was the old white guy; in Linder’s incisions is an infectious energy just waiting to be picked up, remade, expanded, used, and abused.