A boy in a bruise-pink jacket jogs through a dusky idyll, limp-kneed and panting for breath. The grass that flanks the path is dappled with blooming flowers: purple, yellow, orange, and white. In the foreground is an upright piano, incongruously plonked between two trees. The boy staggers past it and out of sight. Seconds later, he’s back where he started. He falters past the piano, vanishes, and rematerializes in an endless, purgatorial circuit. He looks exhausted. Watching this digital animation, I begin to feel exhausted too. Is he being punished, condemned to enact a pitiless ritual? If so, for what purpose?

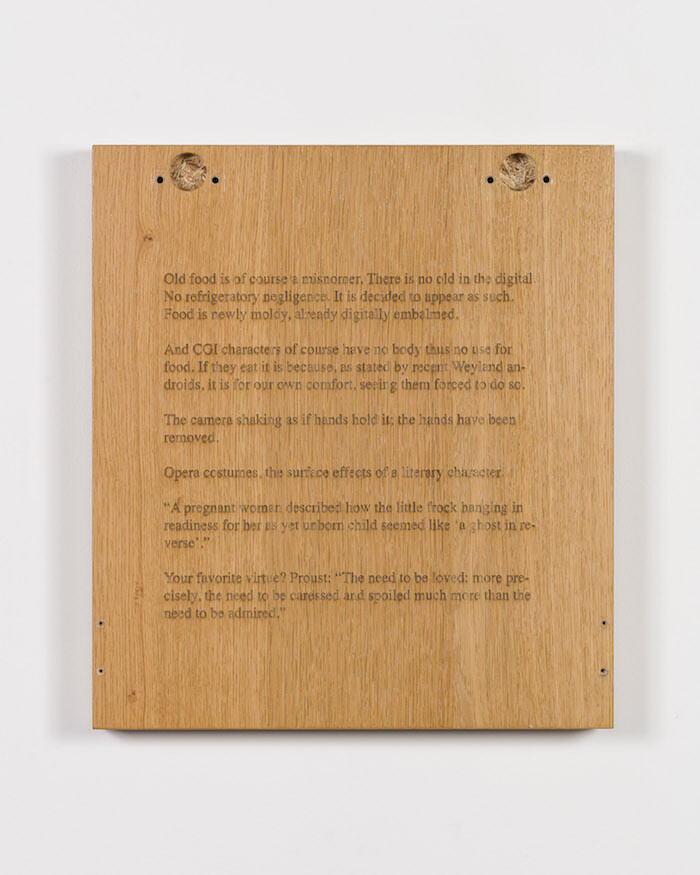

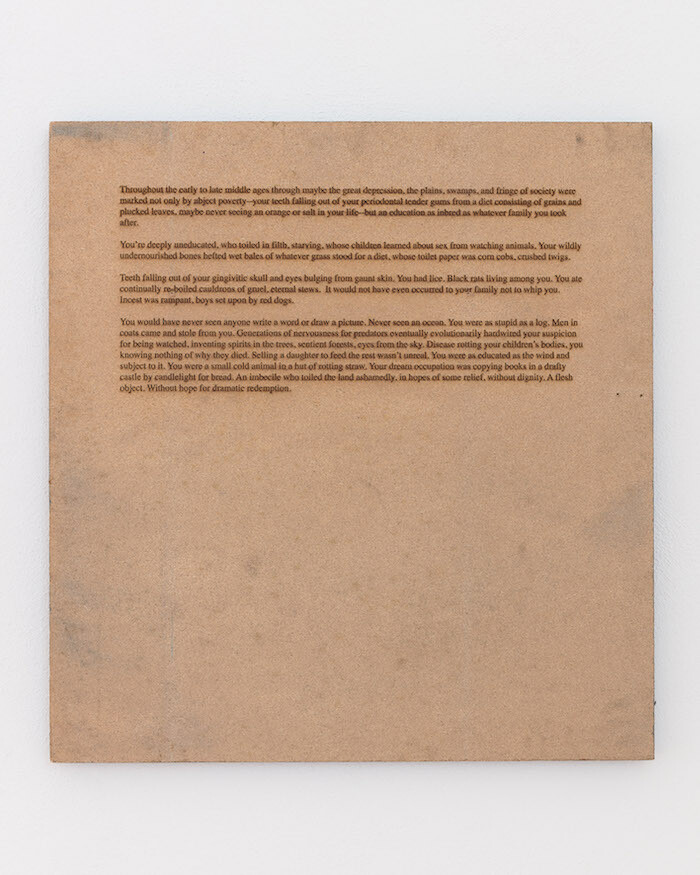

Across from Good Wine (the animations all date from 2017, the year they were shown at Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau), and past a pair of monumental steel clothes rails hung with a spectacular array of old opera costumes acquired from the archives of the Deutsche Oper Berlin (Masses 1 and 2, 2018), a salvaged door is mounted to the wall (Untitled, 2017). Its darkly varnished surface is laser-etched with a cryptic text: one of several such works (all untitled) co-written by Atkins and whoever’s behind the acerbic, anonymous blog Contemporary Art Writing Daily. Some offer arch commentaries on the exhibition (“Old food is of course a misnomer”). Others read like perverted choose-your-own-adventure tales (“You were a small cold animal in a hut of rotting straw”) or eerie Wikipedia entries (“Bog bodies are preserved for millennia beneath peat tundras”). Perhaps the following sentence, from the aforementioned door, explains the boy’s fruitless exertions: “[Ed] Atkins’ protagonists are emotional crash test dummies, all literary characters are.”

The boy is one of three such protagonists in Atkins’s current solo show at London’s Cabinet Gallery. These uncannily lifelike CGI figures—a giant baby, the frightened boy, and a craggy, hooded man who resembles a bit part from Game of Thrones—appear in digital animations, which play on flatscreen monitors mounted to the walls. Unusually for Atkins, who is known for verbose, linguistically challenging works narrated by garrulous cadavers and severed heads, these characters grunt, gasp, and whimper, but never talk. An unspecified catastrophe appears to have rendered them mute, muzzled by grief or trauma.

The only respite from the ominous, sodden mood is slapstick humor. In Good Bread, the baby thumps headfirst into a log cabin. Careening wildly through the air, like a jet-propelled blimp, he knocks over bookshelves and candles before drifting with sudden, spooky calm onto a stool, where he plays some minor chords on a piano. (The piece is Jürg Frey’s minimalist composition Circular Music No. 2 [2012], which functions as the melancholic leitmotif of this show.) In Neoteny in Humans, the looming infant stares at the viewer with swollen, reddened eyes. The monitor is hung in portrait orientation, which lends the animation the unnerving intimacy of a FaceTime call with a ghoulish child. As if this wasn’t disturbing enough, the baby is weeping uncontrollably. Then again, everyone’s crying in “Olde Food,” giving the show the feel of a sadistic test of the viewer’s ability to empathize. Viscous tears run down the characters’ cheeks in gluey, translucent secretions, evoking anguish in the absence of speech.

Correction: one character speaks. In Good boy, the boy who was jogging earlier sits on a wooden stool, hunched and shivering, his back turned. The camera swoops forward with predatorial swiftness—the boy turns around, eyes wide. “Sir,” he gasps, “who is all the dead?” Perhaps he’s referring to the absent opera performers, whose costumes hang like shed skins. Or perhaps he means the bodies we see in up/down, in/out. In this animation, dozens of avatars fall from a great height to land in a jumbled heap of flouncy corpses, or huddle like fretful penguins while credits for an unnamed film scroll over the screen, in a numbing procession of names. The video’s contradictory qualities (it’s funny yet horrific, spectacular yet mundane) are characteristic of Atkins’s work more widely. In his 2012 video installation Us Dead Talk Love, for example, two cadavers embark on a rambling discourse on mortality and love. “I wanted to say something regarding sex and drains,” one murmurs. “As in, I love you. As in: / An abattoir in July.”1 For Atkins, language and art are sites of conflict, in which seduction and repulsion, desire and filth, intimate relations and industrial slaughter, are inextricable.

“Olde Food” bristles with jarring references—Facebook logos, Wagnerian costumes, burger buns, bucolic vistas, flickering striplights, Union Jacks—which jolt the viewer into unpleasant awareness of the artificiality, the constructedness, of Atkins’s spectacle. This strategy is at once aggressively pessimistic (you’re being manipulated, everything’s fake, life is trash, etc.) and affirming (witness what art makes possible, behold this queasy mash-up of cultural worlds!). Atkins’s meticulous sound design is what enables the disparate references in “Olde Food” to cohere into an experiential whole. Physically belittled by the costume racks (they’re just over five meters tall) and thronged on all sides by the distraught, imploring faces of the CGI characters, I am submerged in sound. The crackling noise of rainfall seethes into the space. Birdsong flutters, dies. Piano flows into the mix with funeral slowness, while gasps and groans roam throatily through the air. I leave the show impressed at Atkins’s ability to generate such a menacing atmosphere, but slightly sickened by its effects. And perhaps this is the point: exaggeration is a rhetorical device. Walking through the sun-bathed, flower-strewn expanse of Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, where the gallery is situated, I think back to Good Wine’s endless, aimless circuits—the pointless panting down the path. Thank fuck I am not that poor boy.

Ed Atkins, A Primer for Cadavers (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2016), 200.