The feeling that physical detention is only one aspect of a grander system of constraint haunts “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration.” Curated by Nicole R. Fleetwood, Amy Rosenblum-Martín, Jocelyn Miller, and Josephine Graf, and based on Fleetwood’s book of the same name published earlier this year, the adroit exhibition at MoMA PS1 features work by past and present detainees as well as their extended family, friends, and advocates, alongside pieces by other nonincarcerated artists. In doing so, the show maps what Fleetwood calls “carceral aesthetics,” referring to the wide-reaching ways in which the US prison-industrial complex affects cultural production, and how such artifacts draw an image of our society at large.

On a formal level, several works note how artists overcome the material limitations inherent to forced captivity. Jesse Krimes’s Apokaluptein 16389067 (2010–13) is a vast fever dream. Hung as a floor-to-ceiling panorama on a curved wall, it consists of heaven, earth, and hell drawn in pencil over newspaper images transferred using hair gel onto 39 bed sheets—each of which were individually smuggled out of jail via the postal system. A low plinth in another chamber hosts Dean Gillispie’s nostalgic maquettes depicting 1950s Americana through miniature airstream trailers, dinners, and gas stations. The airstream’s aluminum shell is made from cigarette packet foil; its rivets are pins clipped from the prison sewing shop, and its curtains used tea-bag paper. In an extended caption, Gillispie—who was exonerated in 2017, after serving from 1991 to 2011—says of the work: “they were procuring my life, and I was procuring products from them.” Like many artists in this show, Gillispie adapts the techniques of the carceral state to propose counter-collections and narratives.

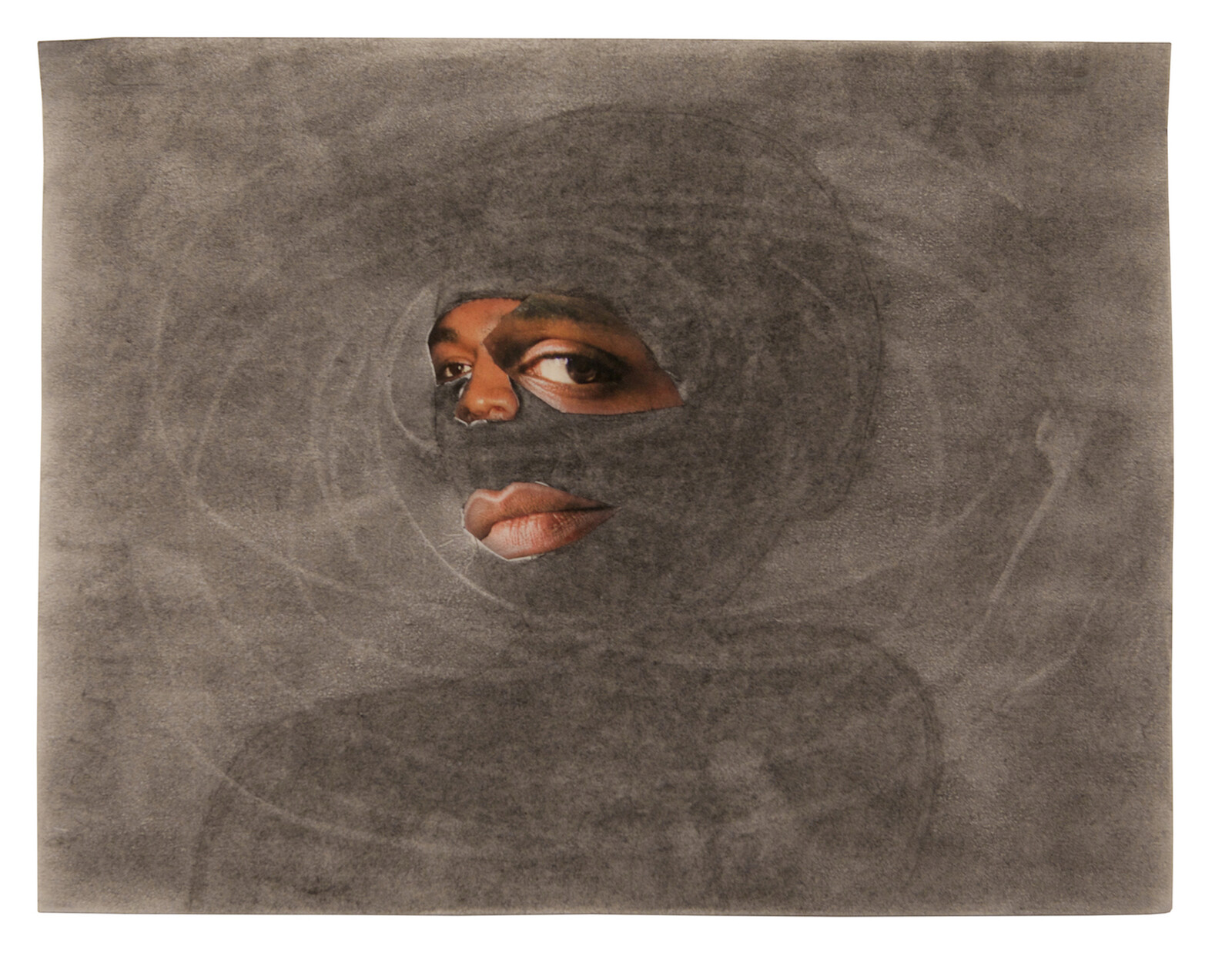

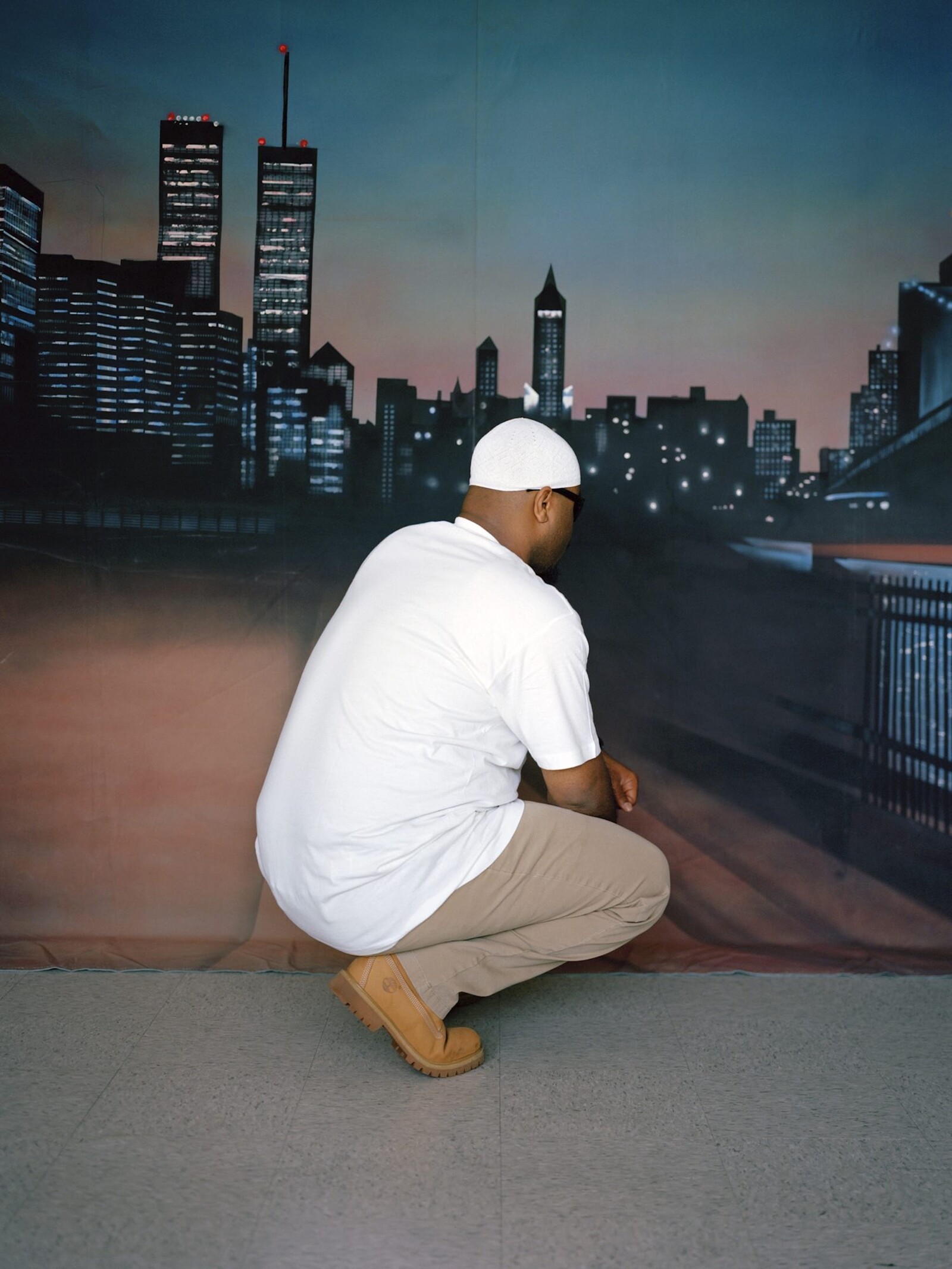

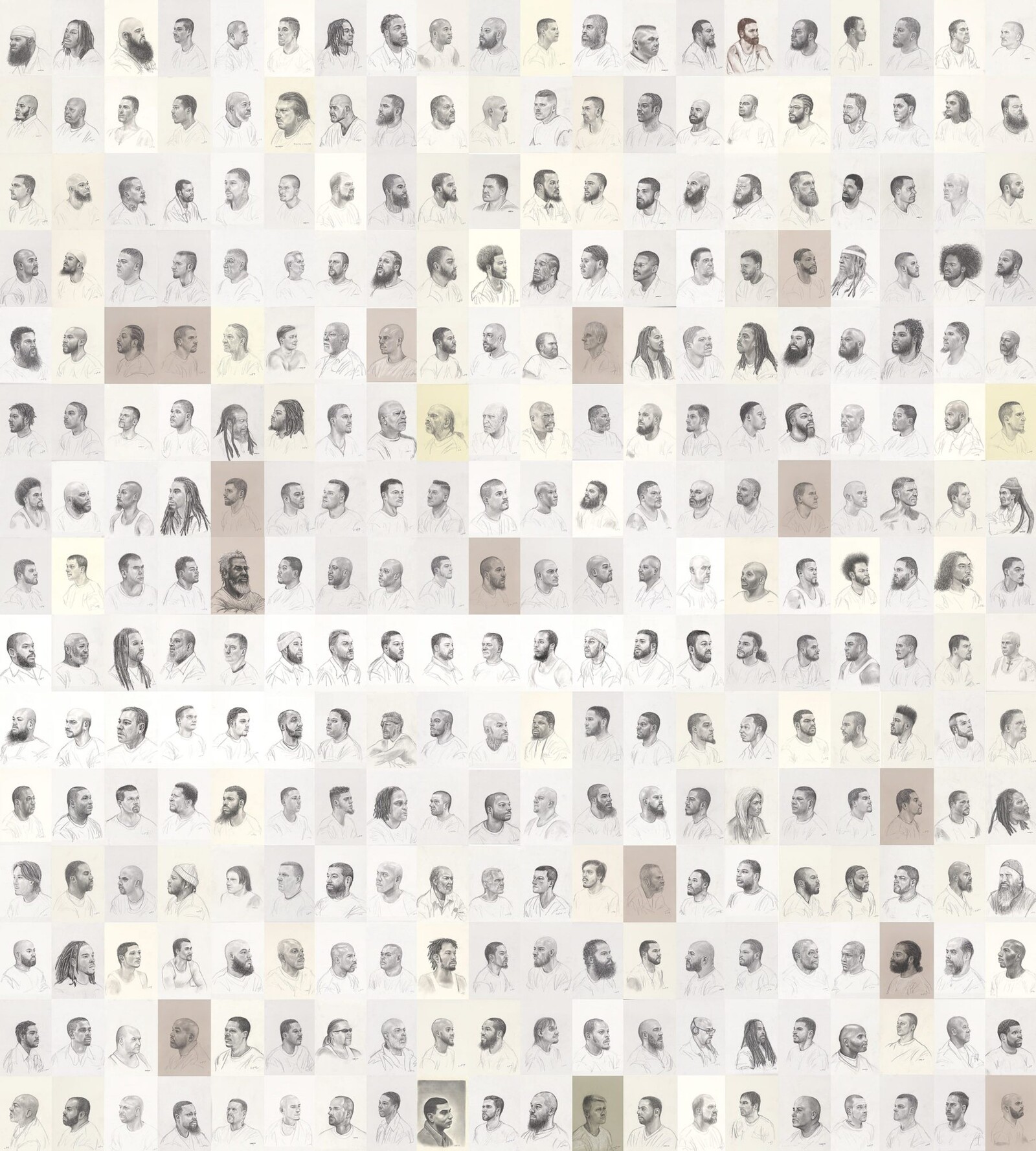

Mark Loughney’s Pyrrhic Defeat: A Visual Study of Mass Incarceration (2014–ongoing) comprises 500 graphite-on-paper portraits of the artist’s fellow inmates. The work could easily be read as an attempt to put a face on those made invisible by the prison system. But it is equally a retort to the ways in which image-making—whether police sketch, mugshot, video surveillance, fingerprinting, DNA test, false witness, or other forensic fantasies—can frame people as objects fit for containerization, or worse. By way of inversion, Krimes’s Purgatory (2009) transfers headshots, both fictive and real, onto bits of prison soap. Hidden in decks of cards that were hollowed out, these contraband images were bootlegged out of solitary confinement—a punishment Krimes endured for refusing to become an informant. Optic regimes are further turned inside out by Larry Cook. In his series The Visiting Room (2019), the artist restages the elaborate painted backdrops in front of which prisoners pose for pictures to send home, complete with everything from the Manhattan skyline to a Lexus parked under a full moon. Cook’s sitters elusively turn their backs, refusing to show their faces. More than simple posturing, these gestures at once demand anonymity against the constant surveillance intrinsic to policing, and reframe each sitter as a reflexive viewer admiring their fellow inmates’ makeshift work.

In a nearby gallery is Ellapsium: mer & Helm (2016), a harrowing painting by Jarrod Owens. Its imagery superimposes the plan of New Jersey’s Fairton Prison, in which the artist was once confined, with the stowage diagram of the Brookes slave ship: a logistical blueprint from 1788 on how to pack Black bodies efficiently, in tiered serial form, into a hold. Plumes of blue bleed from the belly of this compound beast, and leak into a misty orange, sea-like background. This binds the work to another painting’s palette and intent: J.M.W. Turner’s The Slave Ship (1840)—which, like the Brookes diagram, was used by abolitionists to convey the horror of the trade.

Several other works trace the direct continuum between the Middle Passage and today’s prison industry, which grossly affects Black to white people at a ratio of more than 5:1—not to mention those on parole or elsewhere mishandled by the injustice system.1 Activist photographers Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick document life in Louisiana State Penitentiary (though they were not incarcerated there themselves). The prison’s unofficial second name, Angola, refers to the nineteenth-century cotton plantation on whose land it sits, and on whose fields prisoners today toil. Looping on a nearby monitor is the music video for Isis Tha Saviour aka Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter’s 2018 anthem “Ain’t I a Woman”: the protest song recounts, amongst other things, how she gave birth to her son Rasir while handcuffed to a Pennsylvania county jail gurney. Isis’s title is a quote from a speech by Sojourner Truth, the former slave, fierce abolitionist, and women’s rights activist. Hidden within all of these historic parallels is another concept of time, which the show ridicules: the idea that slavery ended in 1865 with the passage of the 13th Amendment. The act abolished involuntary servitude—but did so with the exemption that forced labor is still sanctioned as “a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” It is by no accident that Fleetwood repeatedly uses the word “punitive” to describe the prison system, invoking the legal framework that various contemporary reform activists, such as Ava DuVernay, have demonstrated perpetuates slavery through other means.

While this exhibition is undoubtedly a condemnation of the penal state, it would be narrow to read it only as such. It’s fair to draw attention to PS1’s ties to its parent institution, MoMA, whose board—notably Larry Fink—has been linked to investment in for-profit prisons.2 At its core, however, “Marking Time” tells the stories of people, and how they use bricolage and image-power to fight an apparatus which deprives, distorts, and also attempts to erase them. If the degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its museums, shows like this give hope to the idea of living up to the principles which as a society we profess, such as personhood, dignity, and care. “Marking Time” was preceded this spring by a benefit in which the museum partnered with, and raised funds for, the Innocence Project, a non-profit organization that works to overturn wrongful convictions through the use of DNA evidence. Although such moves do not fully wash the toxic philanthropy permeating through many institutions today, they do point to a provisional politics in which administrators might be learning a thing or two on how to subvert the ties that bind them.

John Gramlich, “Black imprisonment rate in the U.S. has fallen by a third since 2006,” Pew Research Centre, May 6, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/06/share-of-black-white-hispanic-americans-in-prison-2018-vs-2006/.

Alex Greenberger, “‘These Prisons Punish for Profit,’” ARTnews, April 28, 2019, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/moma-larry-fink-statement-cmap-12450/.