Július Koller’s “anti-happenings” are reflexive practices, acting out a lived situation—relating mostly to Czechoslovakia’s repressive, post–Prague Spring “normalization” period between 1969 and 1987 and the limits of artistic activity at the time. Documenting silly or banal everyday activities, including ping-pong games, taking photographs of groups standing in a question mark (his signature symbol), or simply painting and teaching, Koller turns being together with others into Subjektobjekt, a position of personally and artistically transformative “subjective objectivity,” raising collective awareness of the relation between private life and the official public space monopolized by the regime.

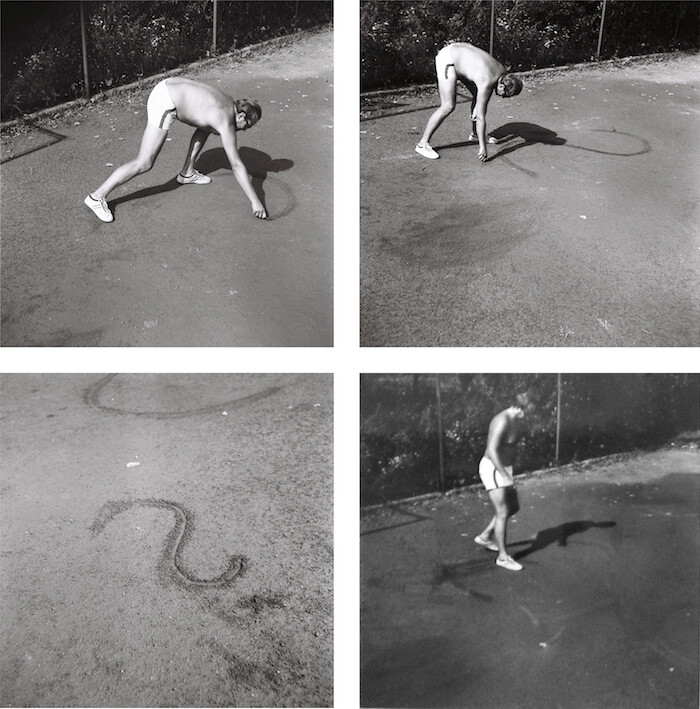

The key anti-happening in the exhibition, which stretches across three floors and still displays only a tiny fraction of Koller’s vast output, is the black-and-white photographic grid Question Mark 1-4 (1969). Showing a shirtless Koller etching a question mark into the clay of a tennis court with his finger, we see two themes converge: for Koller, tennis is a non-artistic activity requiring fair play and obedience to the game’s predetermined rules, while the question mark symbolizes free, democratic communication. This anti-happening then becomes a quietly anti-authoritarian demonstration of the value of intersubjective know-how, granting others—friends, tennis partners, fellow citizens—the same status we would have them grant us.

The anti-paintings Subjektobjekt (1968), Odpadová Kultúra (Junk Culture, 1967), and Trhlina (Crack, 1995) all use poor materials like latex paint, wood fiberboard, and paper, though this work rejects art-world categorization (this is not Pop, Fluxus, Actionism, or Conceptual Art) and stale socialist realism alike. Subjektobjekt’s circular forms are barely discernible beneath hastily applied white paint, and Odpadová Kultúra’s white paper squares covered in colorful smudges look like a hobby painter’s preparatory blotches. Taped onto bigger pieces of brown paper bearing the artist’s name in green stamp print, like goods for sale, the work challenges conventions of artistry without vulgarity.

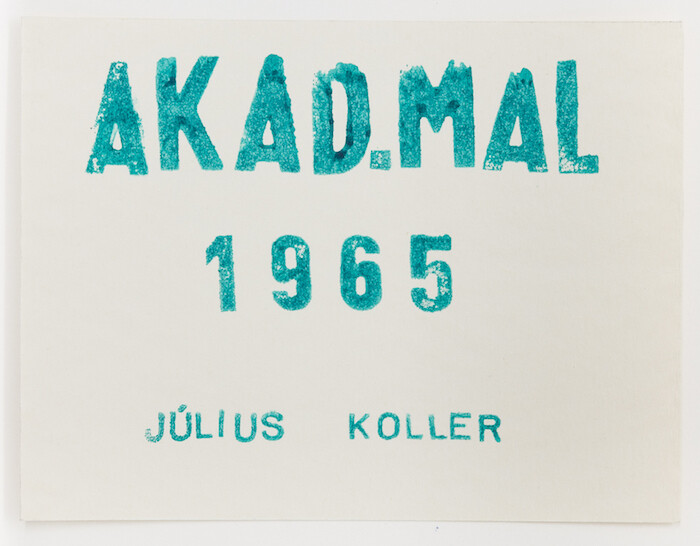

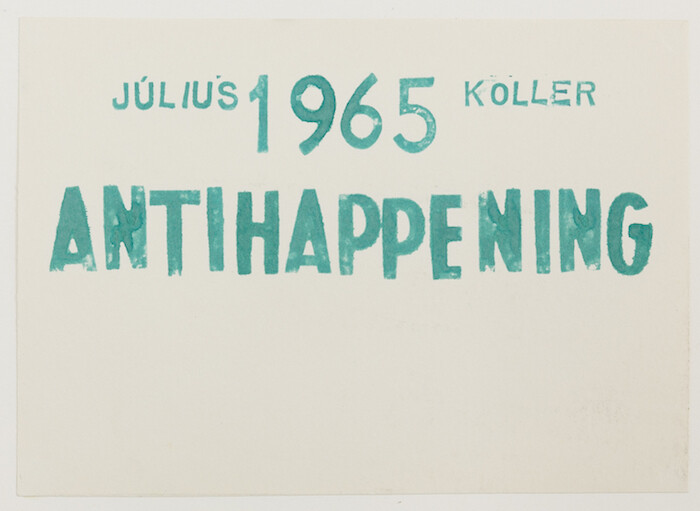

Koller’s “post-communication” pieces are propaganda send-ups, ironic subversions of the regime’s imperious visual language (the imperative voice, bold stamp print lettering), amusingly going unrecognized by its functionaries. The green stamp print from Odpadová Kultúra turns up in the card pieces Akad.Mal and Antihappening (both 1965, both have their titles imprinted on the work using the stamp). The two works represent Koller’s “artistic non-participation” in non-regime-sanctioned exhibitions, while the paper collage Untitled (1971) mimics propaganda by making ecstatic, absurd claims. Governmental public information slogans command “keep off the grass” and “no loitering,” but Koller redeploys their tone and typeface, transforming aggressive instructions into quasi-heroic declarations about “the force of the spirit,” “fate and risk,” and living “without guilt.”

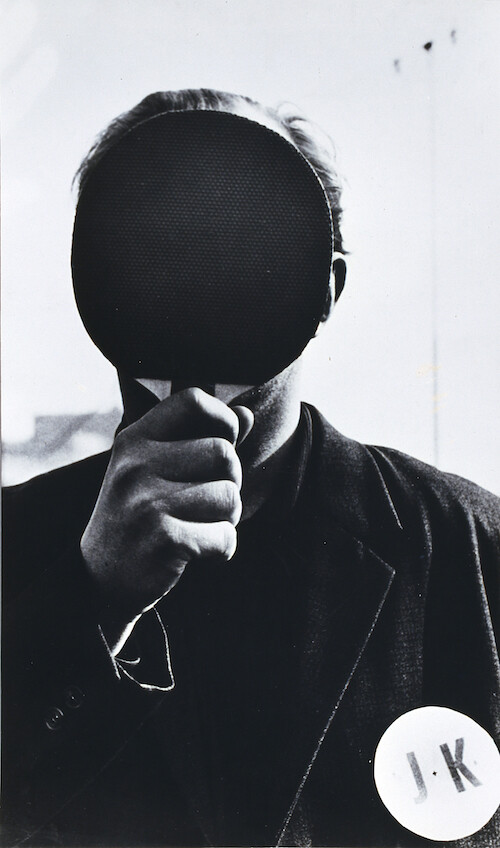

Hanging above the stairs is another example of a characteristic Koller concept: Universal Physical Cultural Operation (Defense) (U.F.O.) (1970) is a reference to extra-terrestrials with specific future-oriented emphasis, another instance of the artist exhorting to change the cultural situation. This black-and-white photograph of Koller’s face concealed by a ping-pong bat can be read alongside two works sharing an aspect of its subject: U.F.O. OBRAZ (1970) and U.F.O.(2003). In the first, it’s a giant canvas sash suggestive of the ones given out in pageants and graduations (or, in Koller’s case, likely the awards presented to workers in Soviet states; it’s just funny that it’s made out of shabby-looking canvas rather than silk). The later work, made of luminescent silver synthetic cloth (the remnant of an old piece of consumer trash) and white latex paint, is the paradoxical product of Koller’s idea of “cosmohumanist culture”—a hopeful worldview counterintuitively placing him in the enlightenment tradition—pointing to the transcendence of all earthly regimes, from the Czechoslovakian Communist Party to the totalizing gaze of aesthetic theory.

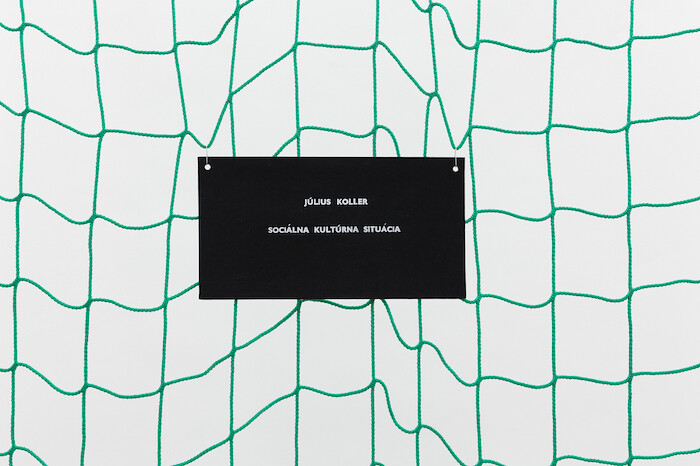

Koller’s concepts coalesce in the deceptively straightforward Sociálna Kultúrna Situácia (1992): a brash green tennis net with the title “Social Cultural Situation” printed in neat white type on a black synthetic leather plaque in the center. The net is a physical manifestation of the rules of tennis, a boundary standing between the two players, separating observable, mutually agreed-upon standards of in and out, success and failure. Dangling from the ceiling in the middle of the main gallery space, it obstructs the viewer’s movement. The work parodies aesthetic autonomy, embodying art’s alienation from everyday life, despite Koller’s claim that everything could count as art. At the same time, it criticizes the bleak determinism of the brand of scientific socialism practiced in post-1968 Czechoslovakia as well as the idea of individualism put forth by the state. The net can symbolize either the rules of the game, which can always be rigged, or the disciplining force of competition. Both systems are equally guilty of making the individual nothing more than a disposable node ushering in the future, and Koller’s imaginative worldview won’t change that, only raising to consciousness our short-lived dreams of freedom.