There is a certain historical irony in the way “ADSVMVS ABSVMVS,” Hollis Frampton’s last major photographic series, became the basis for his first solo exhibition in New York some thirty years after his death in 1984. Frampton himself might have delighted in this inversion of firsts and lasts; his thinking, elaborated in his theoretical writings, was often preoccupied with the origins and overlapping destinies of the media in which he practiced, namely photography, film, and, well ahead of his time, the burgeoning field of computer arts. “ADSVMVS ABSVMVS,” a series of plant and animal specimens in various states of decomposition, evinces these diachronic concerns. Paralleling the work’s archaeological overtones, this excavation of Frampton’s photographic legacy promises to be the first of many shows to bestow upon this major American artist and polymath the recognition he has long deserved.

For those familiar with Frampton’s films, it may come as a surprise that he continued to make photographs: in (nostalgia) (1971), he suggests that he has abandoned photography altogether. The film, which screened at Anthology Film Archives in conjunction with the exhibition at ROOM EAST, provides a voiceover account (spoken by Michael Snow) of the young photographer’s struggles in New York from the late-1950s to the mid-1960s, followed, it is implied, by a turn to filmmaking. As Snow speaks, 13 photographs burn in sequence on a hotplate, each taking a few minutes to curl into balls of smoldering ash. This can be seen as an incendiary act of repudiation, a metaphor for Frampton’s frustration with his floundering career as a photographer. It is also an act of animation, of images literally moved: photography passing into cinema.

Yet Frampton continued to make photographs. While teaching at the University of Buffalo’s Center for Media Study, he experimented with xerographic images and computer technologies, and frequently collaborated with his wife, photographer Marion Faller. “ADSVMVS ABSVMVS” shows that the bridge between film and photography was never burned, and was in fact repeatedly crossed. The work is as explicitly autobiographical as (nostalgia), and the comparison may be more than incidental: the 14 photographs of “ADSVMVS ABSVMVS” might refer to the 14 images described in (nostalgia), though only 13 appear onscreen.

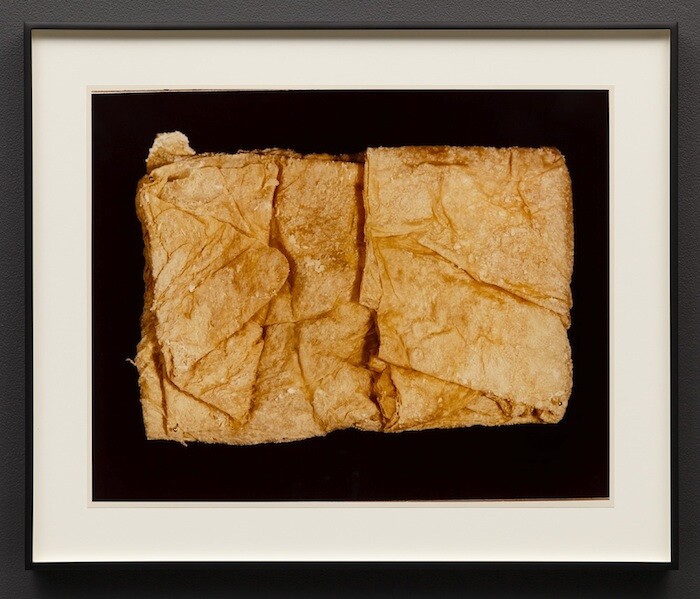

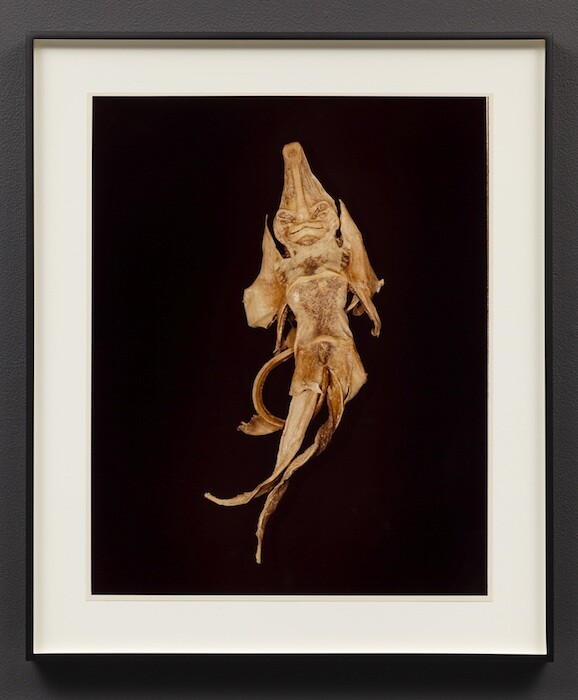

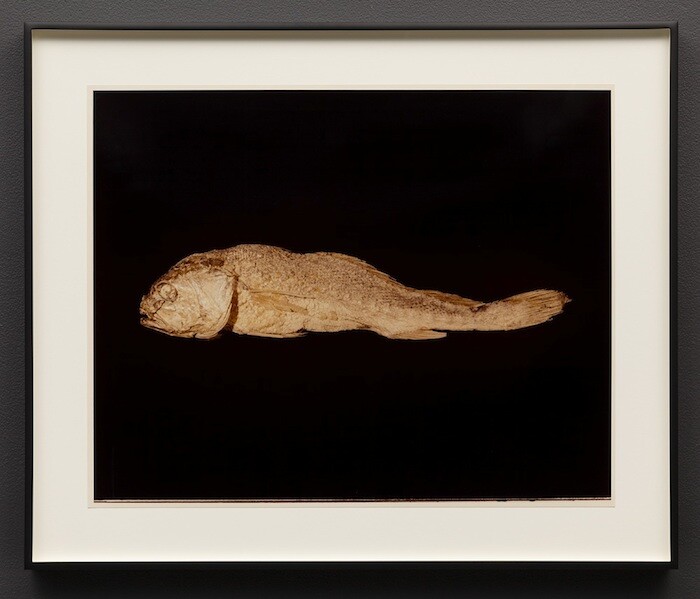

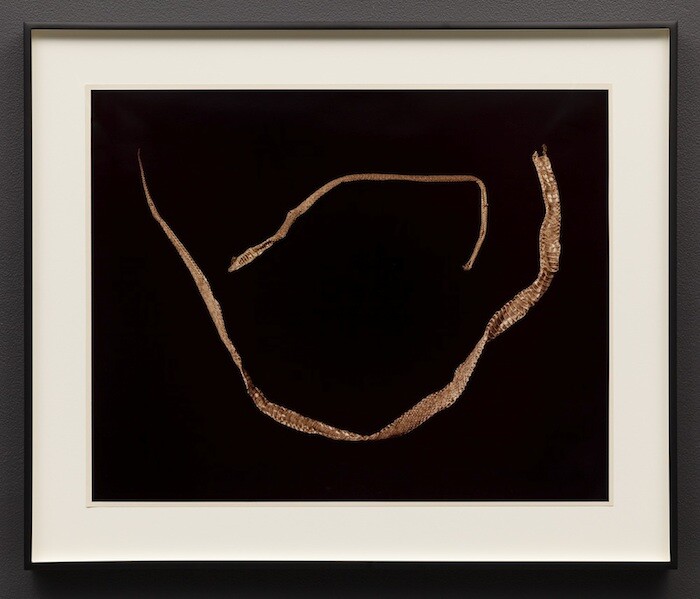

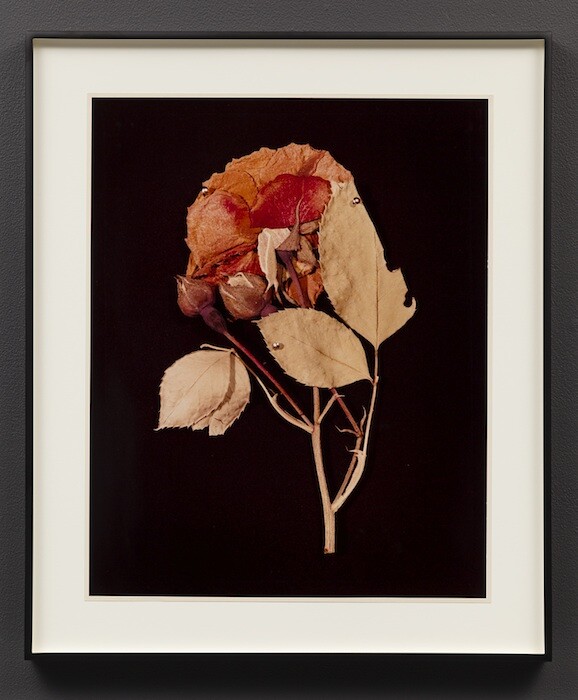

As Frampton notes in the series proposal, the images are “autographic likenesses” of upstate New York roadkill, seafood purchased from Asian markets, and other specimens Frampton acquired over a seven-year period. The 1982 series—which includes photographs of the skin of a jellyfish folded into a box (II. JELLY (Physalia physalis)), the twisted remains of a rat (XIII. BROWN RAT (Rattus rattus)), and a chimaera fish apparently sliced to resemble a dancing marionette (IV. CHIMAERA (Challorhynchus capensis))—presents its artifacts in a solemn and detached manner somewhere between scientific display and memorial altar. These items are both exemplary types and decayed deviations from what they once were. Some, like the skeleton of XII. MOURNING DOVE (Zenaidura macroura), are withered almost beyond recognition.

The work is accompanied by a reproduced booklet authored by Frampton for the original 1982 exhibition at Light Work in Syracuse, New York. For each plate, a brief text indicates the object’s provenance, its appearance, and distinctive attributes. Occasionally it mentions customary practices, symbolic associations, and edible value. There is little account of what happened after Frampton acquired these items, save a note about the broken tail of the midshipman fish in VI. MIDSHIPMAN (Porichthys notatus) having been “surreptitiously gnawed some months later by Maxwell, a cat.” It appears Frampton might have kept his keeping a secret as well: when I asked filmmaker Bill Brand, credited with having found the dove, he was surprised to learn that Frampton had bothered to save it.

Frampton also omits crucial information pertaining to his family. Plate I’s four-leaf clover (I. WHITE CLOVER (Melilotus alba)) and Plate X’s three puckered jalapeños (X. PEPPER (Capsicum longum)) came from Faller, though she is never identified as Frampton’s wife. Similarly, the vibrant red rose in the final plate (XIV. ROSE (Rosa damascena)) was taken from “a funeral wreath,” though the only hint that this came from his father’s memorial service lies in the booklet’s dedication to Hollis Frampton, Sr. Instead, there are intimations of quotidian joys. In the note for Plate X, Frampton recounts how he and Faller celebrated their unlikely pepper harvest with a satisfying feast: “For an afternoon, I parched and flayed, she stuffed with three farces, we sauced and baked. Ah!” The booklet describes a world of roadside walks, vegetable gardening, mushroom forages, and leisurely hours passed with friends and family—an idyll tonally distinct from the somber chord struck by the photographs alone. The booklet and the images compete for the legacy of an irretrievable moment, one through photographic remains and the other through a wry and riddled text. If, as Frampton notes in the preface, “taxonomy is an incomplete discipline,” then the images also fall short of evoking the world to which they refer.

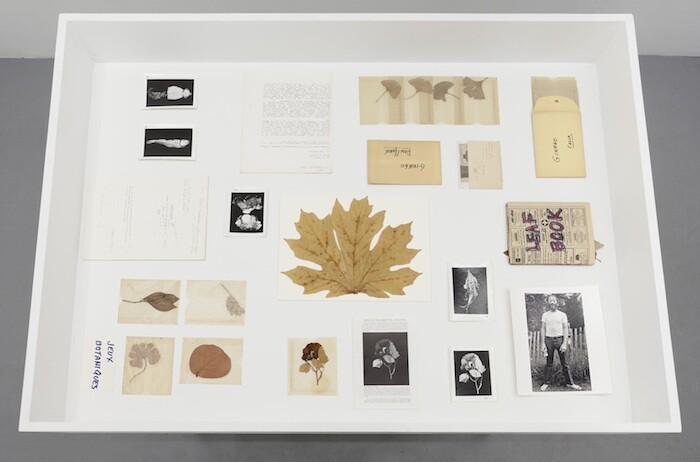

The exhibition additionally features a vitrine displaying clippings, pressed leaves, glassine envelopes, and other objects from Frampton’s estate. Among these, incredibly, is the actual rose, now faded with age, from Plate XIV. These materials underscore a central paradox to photography: however realistically the medium can portray something, it can never conjure full presence. For Frampton, photography was always coming and going. But its play of appearances and disappearances was ultimately one of pleasure. As he writes of the jellyfish in Plate II, “it retrieves… something of the childish adventure of jumping on beached bell jellies after a hard sea storm: ever so momentarily, they resist, and then, suddenly, pressed, liquefy and vanish, leaving behind an everlasting sensation.”