October 31, 2017–February 3, 2018

The fashion for Chinese decoration, architecture, and craft in Europe was the first great wave of exoticism in Western culture. It lasted for more than a century, from roughly 1670—when Louis XIV commissioned the Trianon de Porcelaine, a Chinese-inspired architectural folly, for Versailles—to the end of the eighteenth century. It reached manic heights (Augustus the Strong, prince of Saxony, almost drained the state finances to fuel his collection of porcelains), and left an indelible mark on the history of taste (the “English garden” was also born of a desire to imitate Chinese landscape architecture). So it’s surprising that it’s taken Pablo Bronstein, whose oeuvre draws on eighteenth-century architecture and décor, so long to devote an entire exhibition to it. Perhaps the venue persuaded the Argentina-born, London-based artist that the time had come: a wonderful eighteenth-century apartment in the center of Turin, a room of which is still decorated with frescoes in the Chinoiserie style.

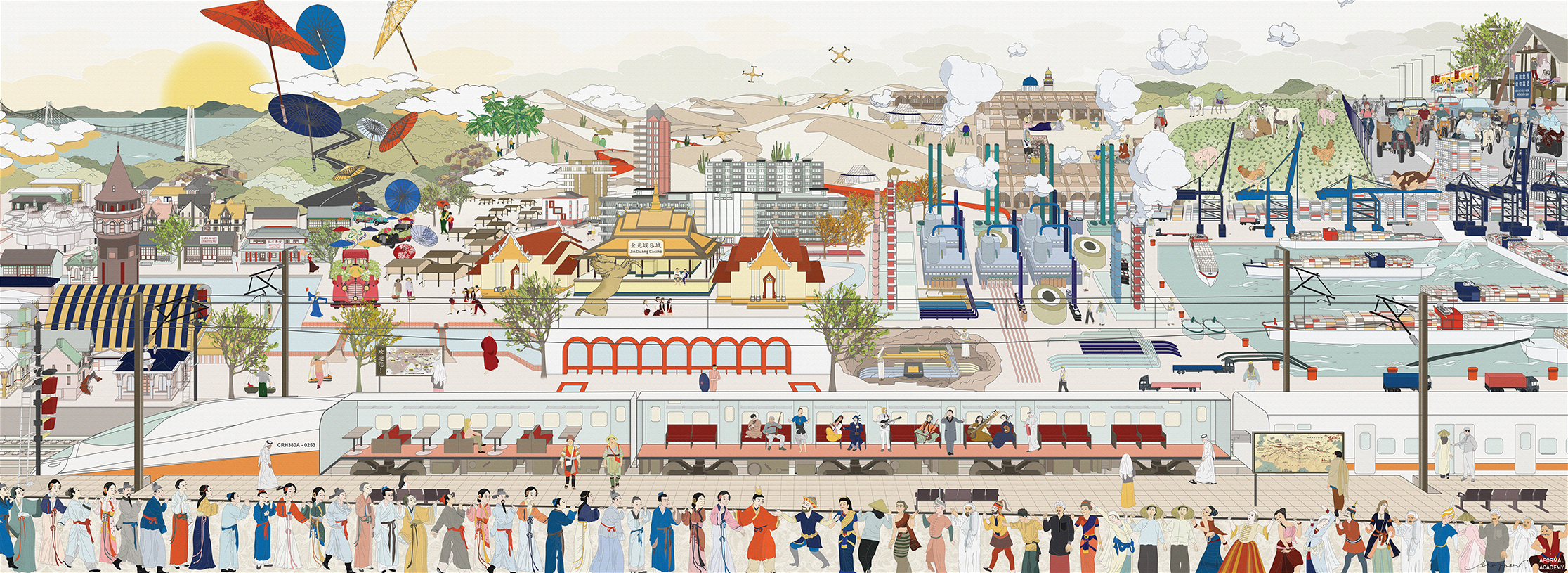

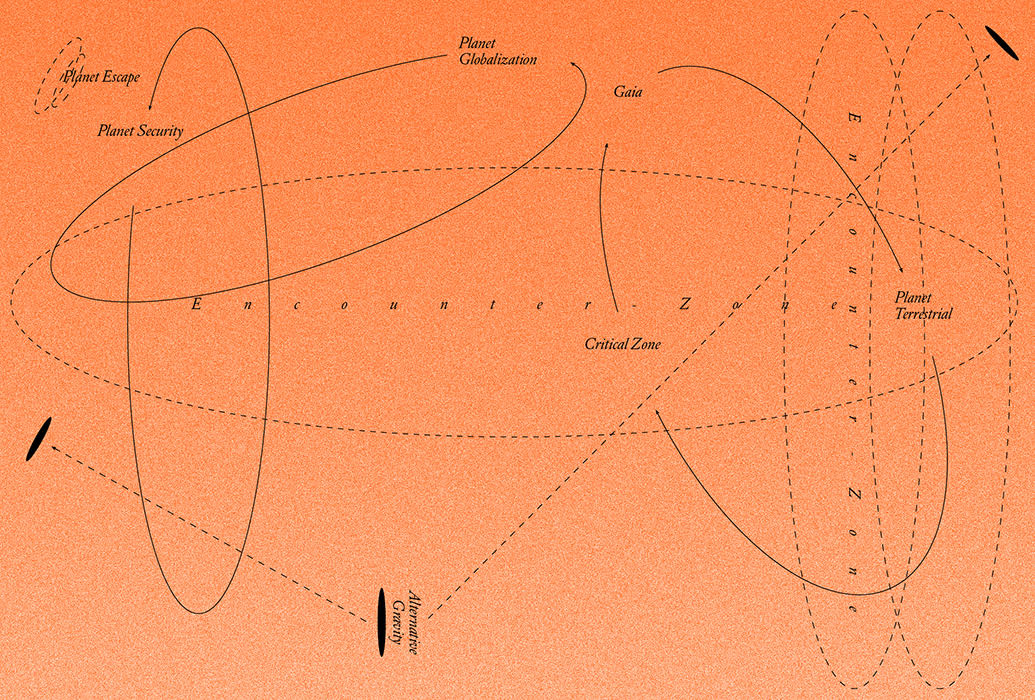

The aspect of this Sinomania that most interests Bronstein is distance. The geographical and cultural distance separating Europe from China is cause for both fascination and misunderstanding, with the representation of each by the other swinging between idealization and caricature. The show’s opening work evokes that distance. Stage design (all works 2017) is a watercolor as narrow and long as an ancient Chinese scroll, painted in the customary Bronstein style, a refined, charming pastiche of the great visionaries of eighteenth-century draft architecture (Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Étienne-Louis Boullée, Giovanni Battista Piranesi). On the left, it depicts a Chinese palace in cross section; on the right, a Baroque theatre. In the middle, ocean waves fade into clouds, vapors, fog—a blurred, floating space for the free play of fantasy and desire. Who is looking at whom? Who is the spectator, who the actor?

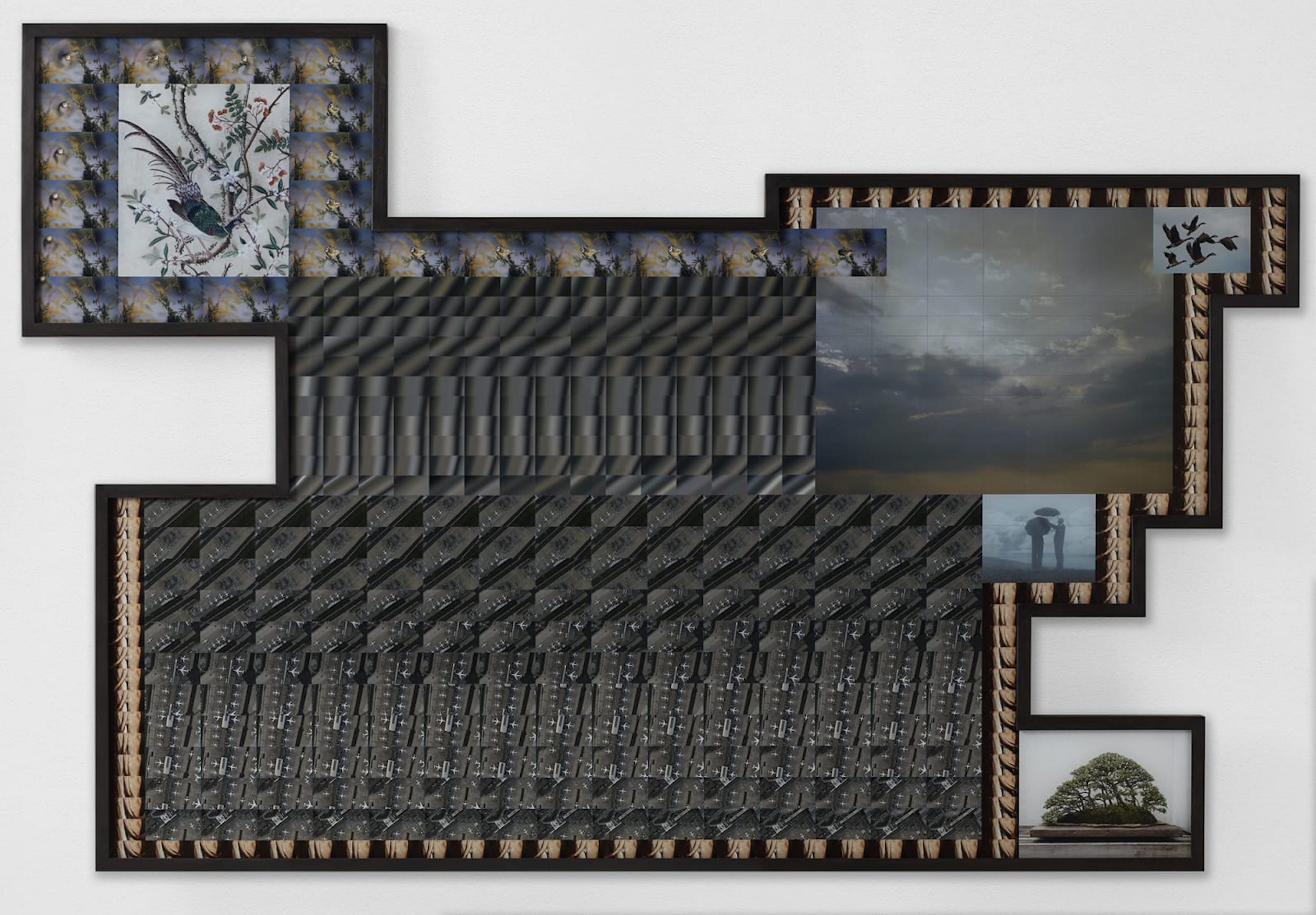

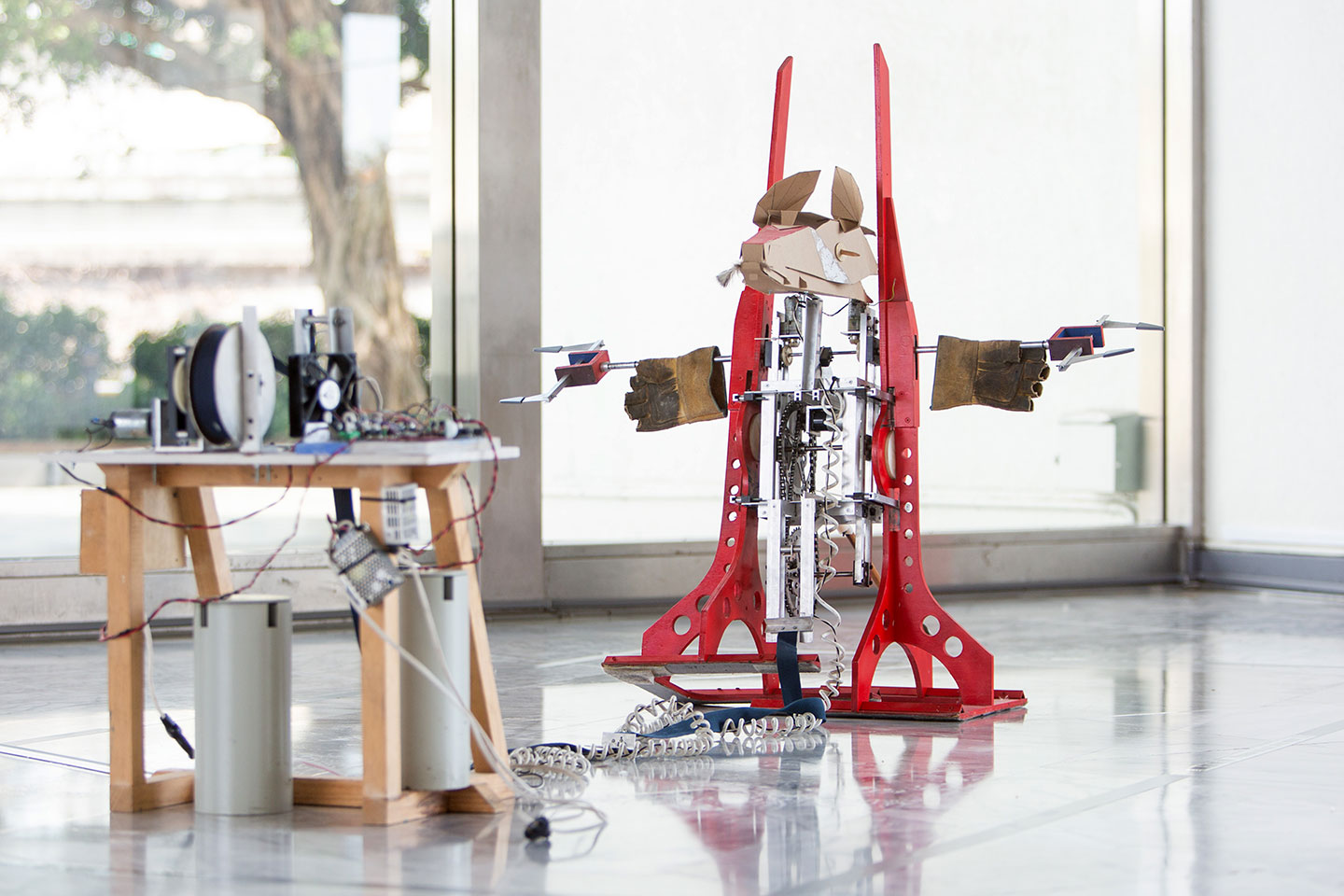

In the press release, Bronstein writes that “China has always returned the European gaze, both hostile and keen.” As the European aristocracy collected Chinese porcelains and lacquers, so the Chinese emperors collected European crafts, or commissioned their craftsmen to produce objects that resembled them. Some of the best works in the exhibition focus on this reciprocity of gaze and the hybrid creations it engendered. For instance, the gouache Paper face-screen with European-style ormolu handle representing the Diana and Actaeon narrative references the trend for setting and framing Chinese objects in precious materials and European decorations, and brings it to parodic extreme: a fan made of simple white paper provided with the most lavish Rococo gilded bronze handle. In three videos that set the pace of the exhibition—shots of dancers rehearsing choreographies—Bronstein has fun speculating on how a “Western style” ballet designed by Chinese court choreographers might have looked. (The most intriguing of these choreographic fantasies is Entertainment at court: 100 European Style ways to greet a casual acquaintance in passing, a marathon of elaborate bows between a male and a female dancer as repetitive and hypnotic as a Balinese dance.)

But ultimately Bronstein’s works are not about the seventeenth century, any more than Jeff Koons’s stainless steel bust Louis XIV—made in 1986, at the peak of the Reagan era—was about the Sun King. The past, here, is a travesty of the present relationship between the West and China. When cheap flights and the internet seem to have done away with distance, it is worth recalling that the fad for all things Chinese was not only an important chapter in the history of European taste, but also told of a long trade war. Worried about their trade balance, European countries tried to limit the import of Chinese wares through protectionism and by producing local, often cheaper imitations of the most sought-after Chinese objects, like lacquers, wallpapers, and porcelain (the first European porcelain factory was set up in Meissen in 1710). This commercial and political history, with which the cultural exchanges between Europe and China are inextricably entangled, prefigures today’s tensions around globalization.

Bronstein doesn't address this historical background directly, instead examining its echoes in the present. Beneath their eighteenth-century graphic attire, some of the works in the show consider what China stands for in the contemporary Western imagination: mass production, aggressive commercial expansion, frenetic urban development. Take the watercolor Large Crane, for instance, whose subject is not the elegant bird that we might expect in this company but a contemporary construction machine, standing between huge concrete buildings. As a concession to Chinese taste, the crane is painted red and embellished with ornamental elements typically associated with antique Chinese furniture, while the buildings are topped by incongruous rolled-edge roofs. On the same line are the wallpapers with which the artist has dressed three rooms of the apartment. There, the elaborate pavilions and exotic landscapes of the adjacent Chinoiserie room turn into a computer-generated combination of architectural elements—pagoda-like roofs, walls, columns—that saturate the walls: architecture as a disposable, mass-produced commodity, ready to fill any given surface, however large. Seen up close, the “largeness of China” is no less impressive to Westerners in the twenty-first century than in the eighteenth, when it was observed from afar.