In “Wages for Housework,” Paulina Ołowska takes up the ongoing task of writing women back into art history. Foksal Gallery Foundation’s exhibition of the Polish artist’s work—alongside paintings and sculptures by Agata Słowak and Natalia Załuska—reflects on the foundations of modern art, emphasizing the interdependency of gender and capital, by reimagining the modernist environment of Warsaw’s best-known white cube.

The show builds on Ołowska’s longstanding interest in complicating the male history of modernism; her previous work has involved research on artistic personas (including Zofia Stryjeńska, Janina Kraupe-Świderska, and Maja Berezowska) and engaged with media and visual idioms that blend “high” and “low” culture. More recently, she has turned towards an investigation of “the grotesque” as formulated by Mikhail Bakhtin: its main principle of corruption as a means of subverting the dominant discourse is apparent in works focused on points of breakthrough, crisis, and change.

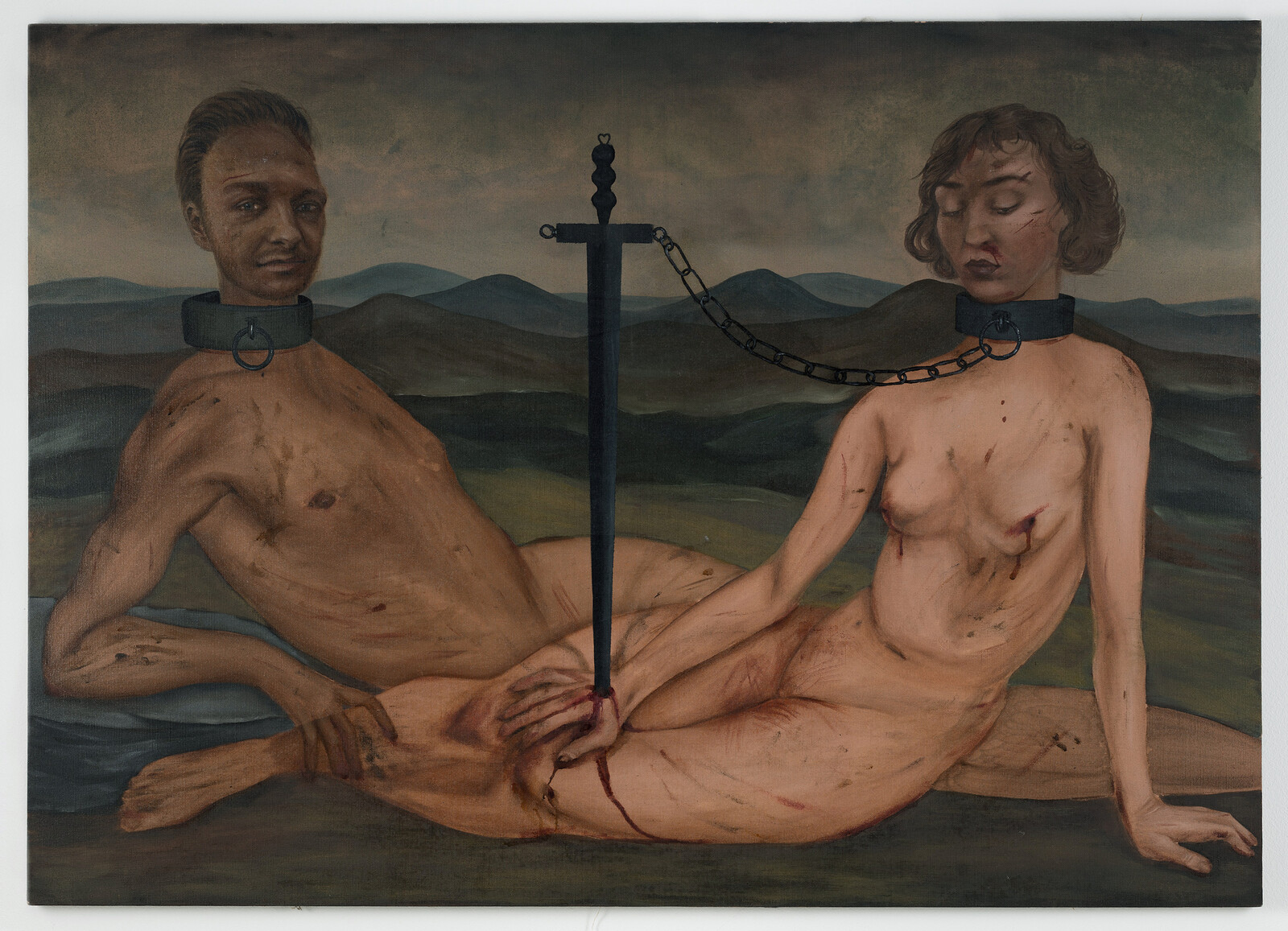

“The grotesque,” notes the writer Tess Thackara, “is inherently associated with the feminine, long having shaped depictions of the female body—prostitutes, femmes fatales, and sorceresses.”1 These transgressive figures populate the first part of the show. Słowak’s painting The Sacrificial Rabbit (all works 2020) depicts three female personages with the animal offering hanging in the background. The trio, engaged in a sensual exchange of gestures and gazes, seems to embody the coming of a new order: one that is intransigent, violent, and mounts a challenge to the status quo. The promise of revolt also lies at the center of Słowak’s Opportunities. In an uncanny paraphrase of the biblical scene, a woman on a hay-filled wheelbarrow is offered an already bitten apple by a woman-snake hybrid. Ołowska’s monumental Alcoholic, Lover, and Seducer portray the limited set of roles that a “liberated” woman can be expected to assume: the protagonists’ characteristic traits, as if composed according to past iconographical conventions of portraiture, are specified through attributes—perfume, pearls, flowers, bottles. Yet Ołowska’s majestic femmes fatales are in no way regretful, disappointed, desperate: they seem oblivious to the parts that they were supposed to play, resistant to the stereotypes intended to categorize them.

“Wages for Housework” borrows its title from the second-wave feminist movement, and specifically from Silvia Federici’s call for domestic work to be valued as labor. This influence is acknowledged in an ironic subversion of the very notion of housework: the large glass windows on the first floor of the gallery have been smeared by the three artists with a mixture of dark fluids. This level accommodates furniture from Słowak’s house, including a closet, a leather couch and a broken mirror: the gallery space, usually a sterile environment designed for untroubled contemplation, is transformed into an eerie home. With the artists’ intervention, visitors are forced to witness the muddy underbelly of the modernist narrative.

The exhibition overspills its boundaries: it is sometimes difficult to determine where scenography ends and where an artwork starts. This is the case with Załuska’s small abstract composition, resembling a winged retable, hidden in the half-open wooden closet. Two of her larger pieces (also both untitled) dominate the lighter, less crowded space on the upper floor. The two-sided abstract constructions, of varying thickness, material (cardboard and wood) and color (plum, ochre, and gray) don’t shy away from exposing their irregular undersides: they resemble constructions in process, shapes frozen mid-form.

When you are not admitted into the canon, your only recourse is to question it. When all irregularities are to be assimilated, deviations from the norm suppressed, the destructive and subversive properties of the grotesque are a welcome reminder of the hidden roots of modernity. Amelia Jones’s 2004 book Irrational Modernism set out to adjust the traditional story of the predominantly male avant-garde, and to challenge “the very rationalism of art history itself”2; recent reassessments of the spiritual bases of abstraction (see the major shows given to Hilma af Klint and Emma Kunz) have continued this work, and form a subversive tradition in which this show participates. “Wages for Housework” may sound at first like the repetition of second-wave slogans; nevertheless, especially in contemporary Poland, some questions are worth asking twice, and some demands need to be repeated.

Tess Thackara, “Why Contemporary Women Artists Are Obsessed with the Grotesque,” Artsy (January 2019) https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-contemporary-women-artists-obsessed-grotesque.

Amelia Jones, Irrational Modernism (New York: The MIT Press, 2004), 12-13.