Suzanne Jackson was drawing two lines by 1968: One she traced over and over in watercolors and oils and strange new acrylics, of wingspans and the receding landscapes of her adolescence; the other was a limit, drawing a boundary against a relentless decade and the demands of her contemporaries.

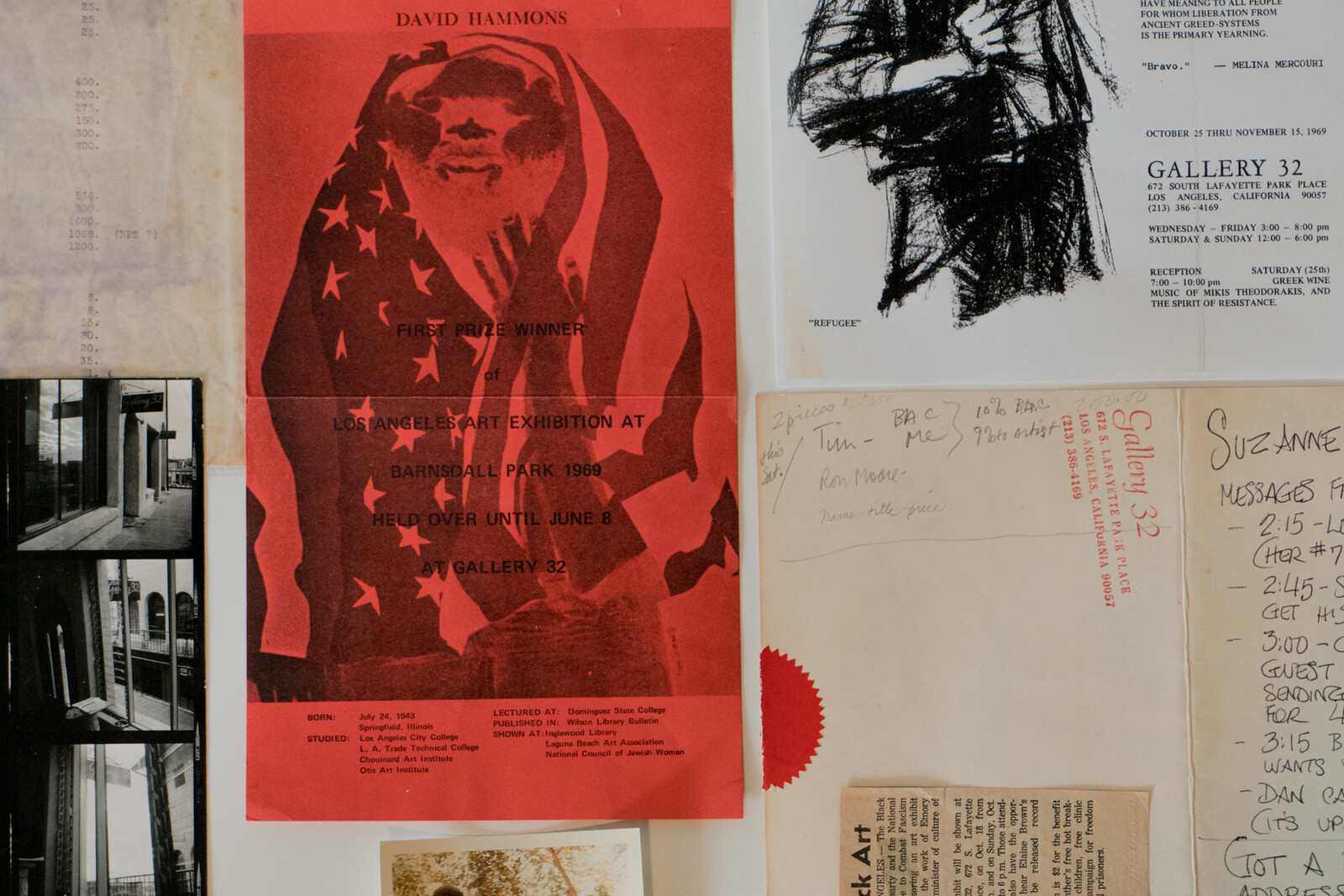

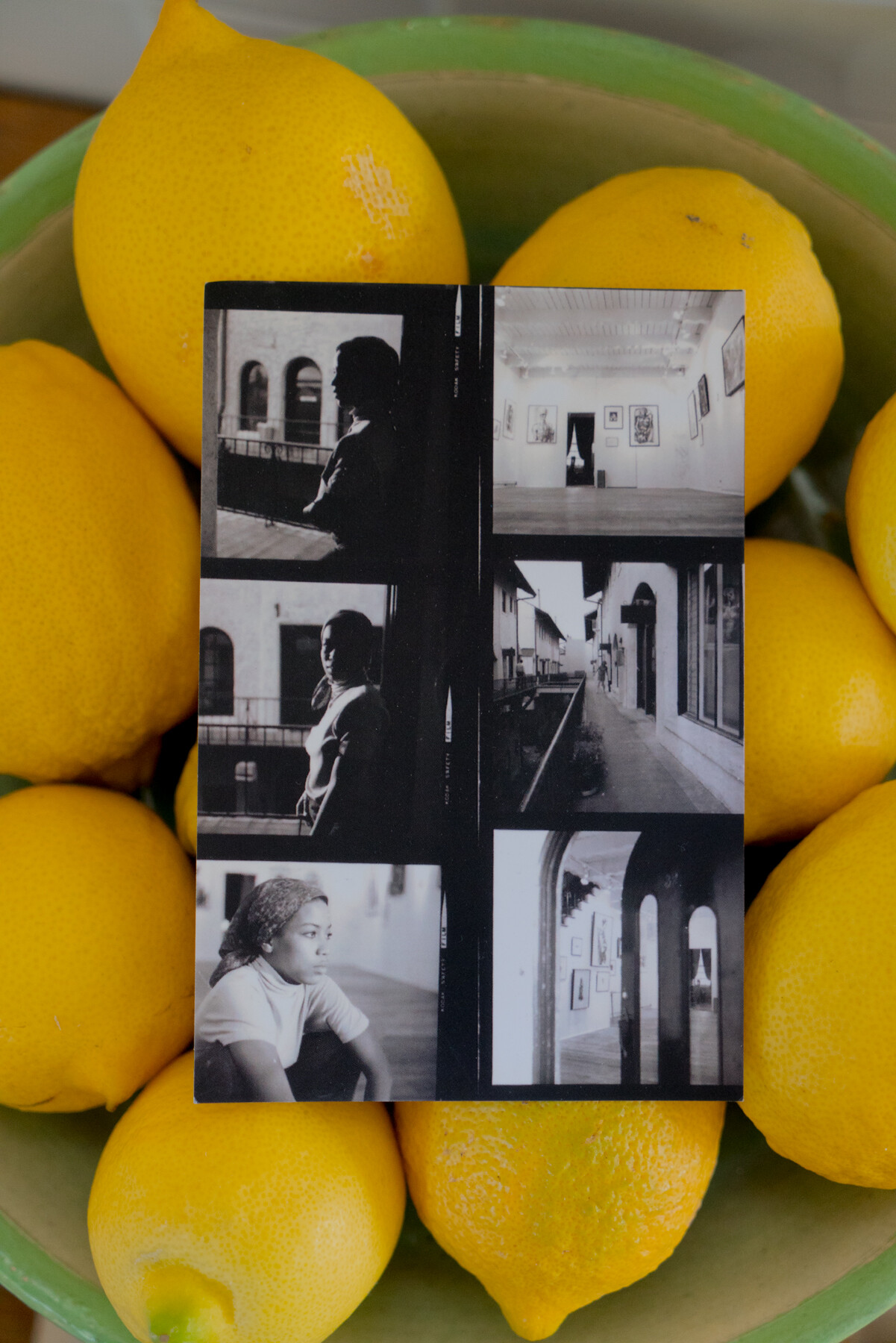

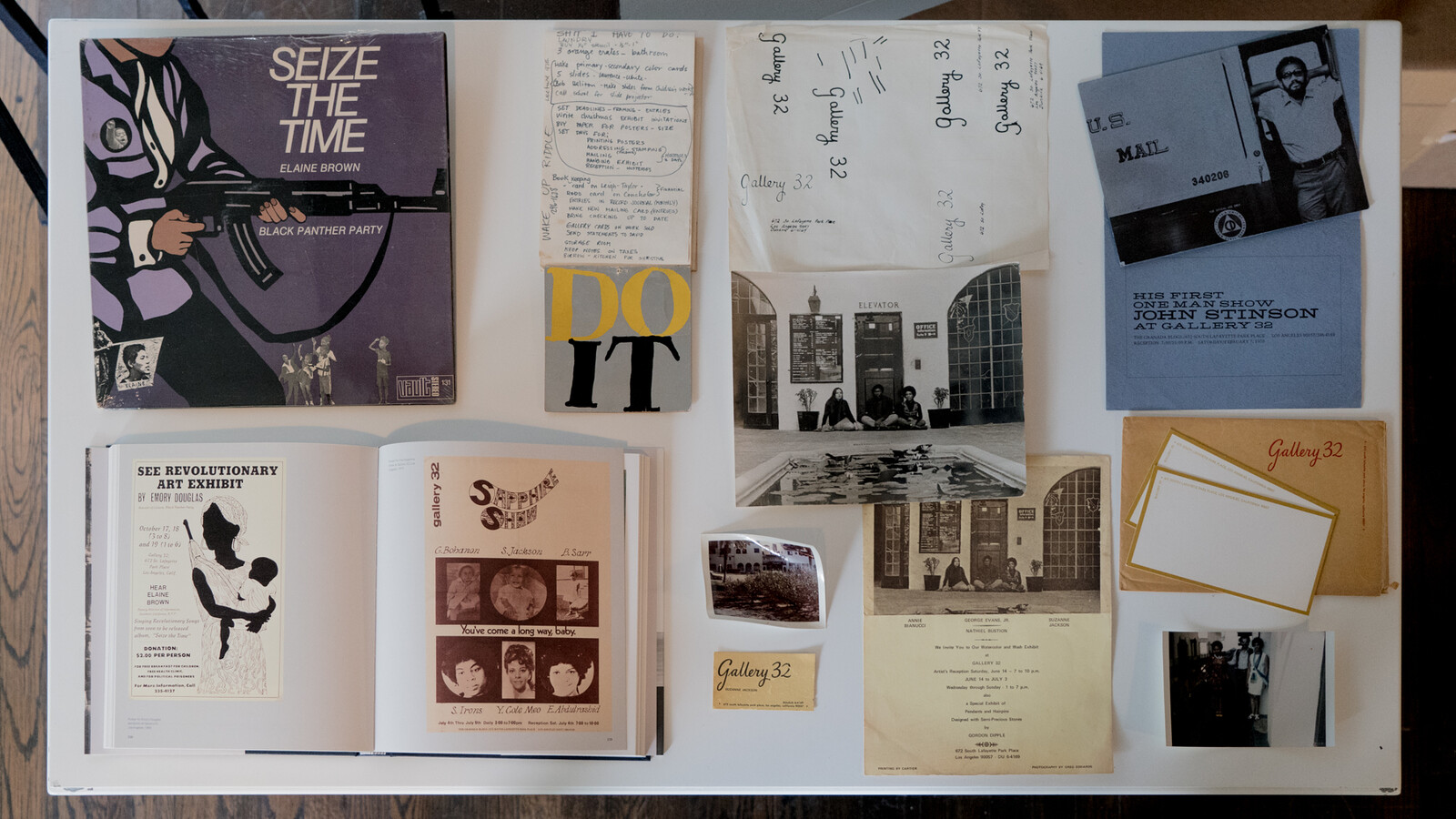

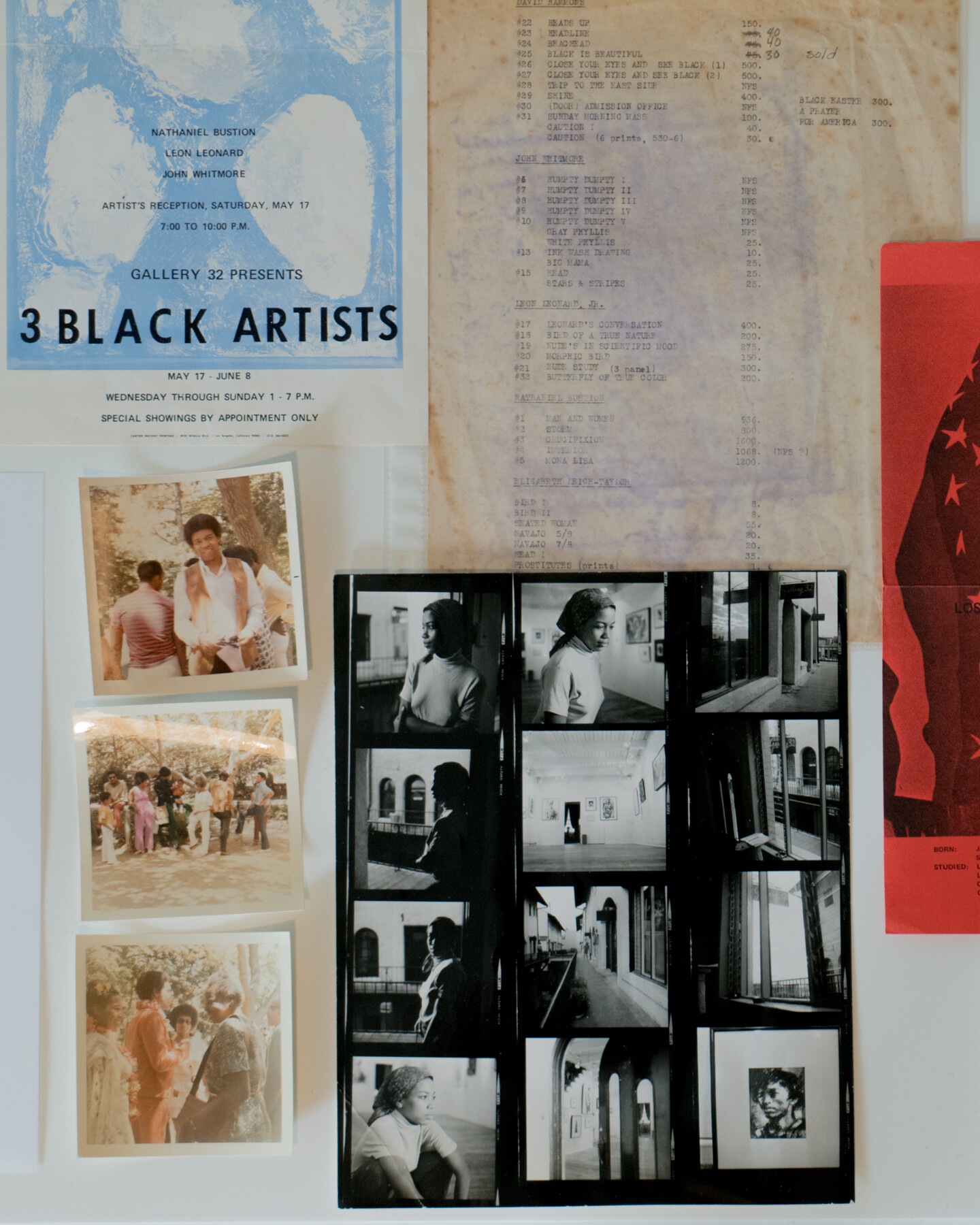

Her lines intersected at Gallery 32. Sectioning off half of her live-work studio in the Spanish-style Granada Buildings in MacArthur Park, Jackson handed the floor over to her classmates and teachers from the then-nearby Chouinard Art Institute (which has since merged with CalArts) and Otis College of Art and Design, including David Hammons and Charles White. She also hosted fundraisers for the Black Arts Council, Watts Tower Arts Center, and Black Panther Party, as well as “Sapphire Show” (1970), the first survey of black women artists in Los Angeles. Evidence of this history is on view in the foyer of O-Town House, a new gallery located in the Granada Buildings, just a floor above and a half-century behind the original Gallery 32. Folds of handwritten invitations, curling photographs, price lists, exhibition announcements, and contact sheets fill a line of vitrines, laying out an ephemeral context for the exhibition of Jackson’s works from the past decade inside. The late 1960s were tumultuous, quick years, producing the Watts Rebellion, assassinations, riots, and sit-ins. When Jackson exhibited her paintings from those years, often material studies, pourings of pure color on—or making their own—soft or shifting, shining, glossy forms, the Panthers offered unsolicited critique. They wanted another Emory Douglas, the Panthers’ Minister of Culture who was the movement’s newspaper illustrator and exhibited flattering portraits of party leaders. “They said, ‘Well, why don’t you have guns in your work?’”1 When they asked for the keys to Gallery 32 to make it a space for meetings and exhibit their own kind of work, she refused; the room would continue to be a community salon.

“[W]hat do you know, and from where do you know it?” Kellie Jones cites Katherine McKittrick, who proposes that all knowledges are geographic. Black geography is inextricably tied to the black body; black is a concept that “is cast as a momentary evidence of the violence of abstract space, an interruption in transparent space, a different (all-body) answer to otherwise undifferentiated geographies. … What actions does the object want from or require of its beholder?”2 The US had seen over a century of black migration westward. Jackson’s family was carried even farther west than California, eventually settling amid the pre-statehood wilderness of Alaska. She grew up as a member of the local Arctic Audubon Society, a grassroots bird conservation network in Fairbanks, and though she has depicted a variety of animals and aspects of nature over the decades, like the sweet, stormy showdown in Marilyn and Maya Watch Fog (2006), these creatures and their movements have remained her most frequent subject matter.

Alternating between thick, dense abstract fields of the sunny patterns and stipples seen in Garnet Zagbite and finding joy in the mirror, her radiant Good News Baby! (all 2016), and her figurative work, fluff a faint profile of a bird’s head with blocks of pigments in watery pastels and blooming marigold. The diptych Blowing birds, in the land, in the hand (2014) has two birds on the same flight path, each gliding through their own horizontal swaths, charting their line between treetops and pools of water. Bushes of tropical mango-hued stroke-feathers encircle a pair of coolly muddied twin blue birds in Toucan Negotiating Two Crows (2003–14), playing out against the white clouds or sands of the untreated background. In the corner of the gallery, the dark and small birdmusic – holding on to a sound (2011) is a last, drowning gargle: sheaths of paper rubbed with pewter and smeared with some blues, red, rust, and what appears to be a good smear of crude oil, all crinkled and dried together.

Jackson responded to the Panthers’ request for occupation of Gallery 32 with a poem, published in her first book, What I Love (1972):

…I say you

intimidate

the people

you say that

the people have

no minds for

dreams for

making some

kind of pleasant

fantasy within

their own realm

of wishful need.

you say

the people have

no capacity

for filling in

or for making

new images

within their own

minds when

they look at

art—or at most

what you say

is that the

people should

not be allowed

to delve

into fantasies

which might relate

to their own

reality, more

than to yours.

Jones’s indispensable resource chronicling this generation, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, was open to the artist’s page of poem-protest at the front desk, lying next to the original Gallery 32 guestbook, whose crackling, yellowing pages held everything from well wishes on an opening night to announcements for an Immortality Jam Benefit alongside David Hammons’s “Body Prints” (Friday, August 1, 1975) to Jackson’s “moving to New York good by [sic] sale” (September 21–23, 1979). Visitors to “holding on to a sound” are meant to sign their names in the same notebook, where there are many more blank pages ahead.

From interview with Mason and Suzanne Jackson, A TEI Project (Los Angeles: UCLA archives; recorded August 12, 1992; released September 23, 2011), 40 and 197.

Kellie Jones, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2017), 16–17, 158.