In What is Philosophy? (1991), Deleuze and Guattari write that “art is continually haunted by the animal.”1 Looking back through millennia of artistic production, we see representations of our beastly counterparts everywhere: as companions, deities, workers, or raw material. Likewise, John Berger has argued that “the parallelism of their similar/dissimilar lives allowed animals to provoke some of the first questions and offer answers.”2 Yet a life in common, and the reciprocal gaze that humans and animals once shared, was lost in the West with the development of nineteenth-century capitalism. The practice of German-Iraqi artist Lin May Saeed brings the image of the animal from the periphery back to the center.

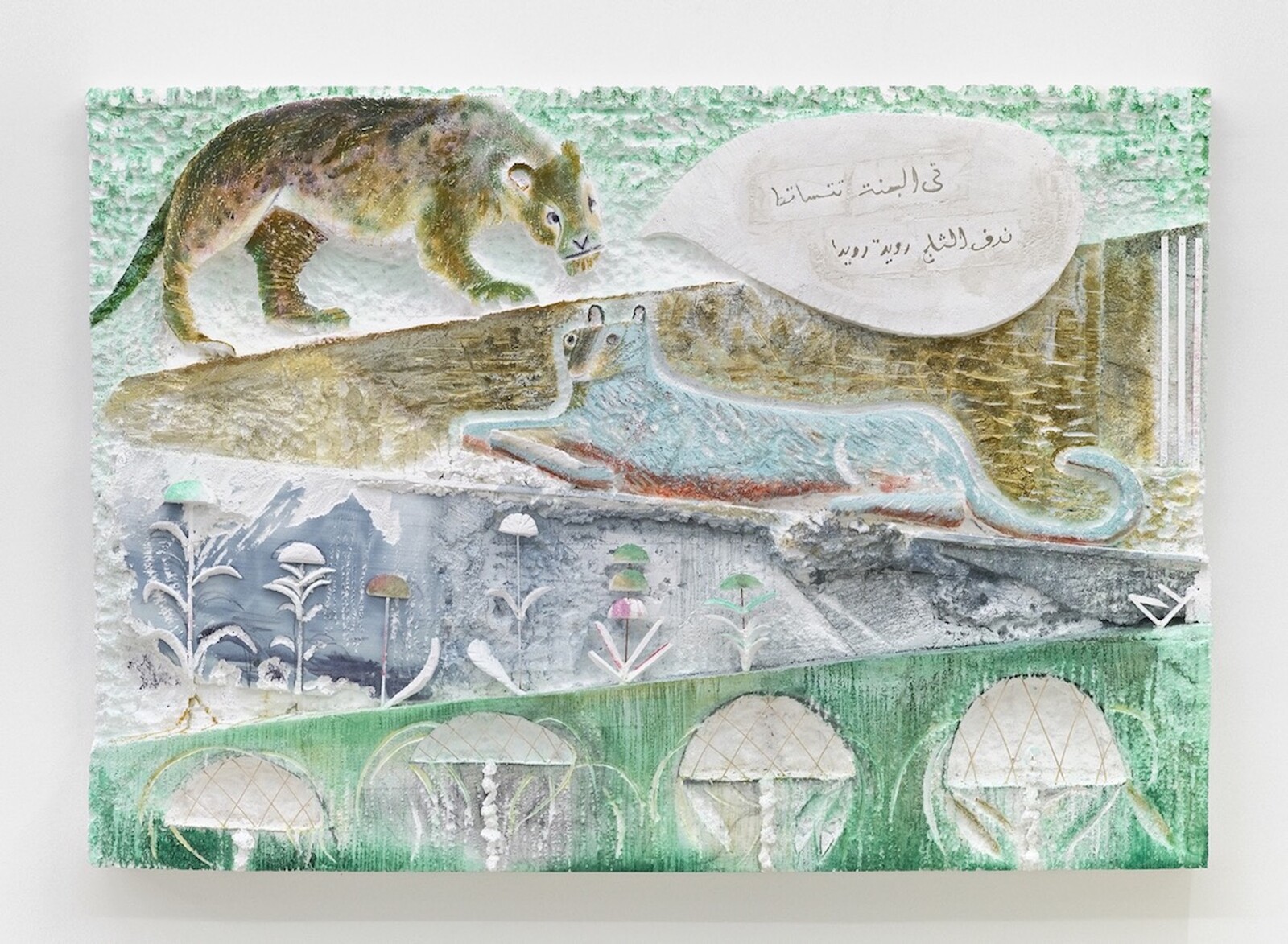

Saeed devoted her life, sadly cut short by brain cancer at the age of fifty last month, to the cause of animal liberation. Her work avoids agit-prop depictions of animal suffering and instead draws on myths, stories, and fables so that we might “imagine a kind of time travel with a focus on the human-animal relationship” and “think about our common future” by looking at the past.3 “The Snow Falls Slowly in Paradise,” in which Styrofoam sculptures and reliefs, figurative wall works, drawings, and videos are shown alongside animal sculptures by the prominent Weimar sculptor Renée Sintenis, spans the artist and activist’s short career. During the last months of her life, Saeed worked closely with curator Kathleen Reinhardt to create a dialogue between two bodies of work rooted in different time periods, generations, social contexts, and materials, yet which share a radical sense of empathy and reverence for other species, as shown by their attention to the intricacies of animal gesture and behavior.

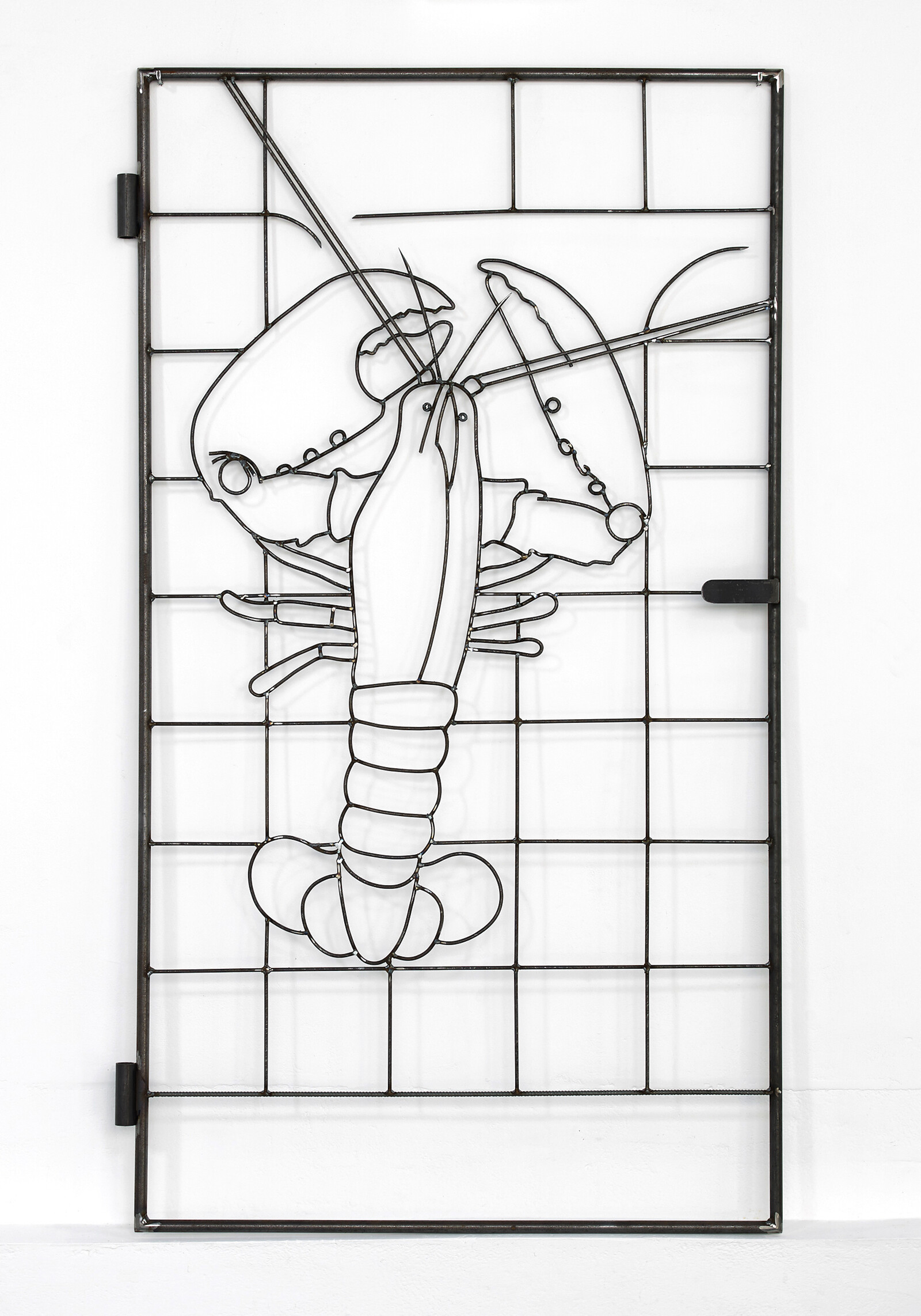

Some of Sintenis’s bronze sculptures could fit in the palm of a hand; their miniature size and formal simplicity lend them a talismanic quality. Saeed’s work possesses a similar sensitivity, yet on a larger scale and with very different materials. Unlike Sintenis, who always portrays animals in isolation, Saeed often stages the encounter between the human and non-human. St. Jerome and the Lion (2016) derives from the biblical story of the saint removing a thorn from the lion’s paw, presaging a lifelong companionship; The Liberation of Animals from their Cages XV (2014) shows a masked figure carrying a lamb out of captivity. The style of these wall-mounted sculptures—inspired by the ornate graphic gates common in German garden communities—imagines compassion, coexistence, and interspecies friendship as a form of vernacular architecture.

The somnolent atmosphere of the group sculpture Seven Sleepers (2020), which depicts the Christian-Islamic legend of a group that took refuge from persecution in a cave and slept for centuries, communicates silent protest or shared trans-species dreaming (a noiselessly howling dog nods to Sintenis’ 1946 sculpture Klagender Trümmerhund, or Wailing Dog in the Ruins). In House of the Rising Sun II (2014), installed in a fireplace at the entrance to the museum, a human figure kneels to warm their hands by the electric light of synthetic candles. A monkey perches on a pile of wood while an elegant dog, crafted from graceful curves of white painted steel, calmly sits by their side. Dignity, hope, and reconciliation permeate this tableau’s expression of fellowship between humans and animals. Closer to life-size and crafted almost exclusively from “poor materials” like polystyrene or salvaged wood, a pack of animals occupy the main exhibition space. In lieu of pedestals, they stand atop skeletal wooden boxes, which also serve as their transportation crates. Their posture and expressiveness lend each of these works a gravity that belies the physical weight of the sculpture. Saeed’s use of a lightweight, breakable, non-biodegradable material like Styrofoam gestures towards the fragility of all life while underscoring human impact on the world we share with our fellow animals.

“The Snow Falls Slowly in Paradise,” to give the show its full title, articulates a social critique that is neither aggressively didactic nor emptily rhetorical, but can instead be found between the nip and the bite. Berger wrote that “animals first entered the imagination as messengers and promises” and only later assumed a more domesticated and distant imaginative role, whether as house pets or the fantastical figures familiar from children’s cartoons, toys, and morality tales. Lin May Saeed’s exhibition pushes back against this shift, reinstating a “reciprocal gaze” which shows, ultimately, that to liberate animals is to liberate ourselves.

Deleuze and Guattari, What is Philosophy (London: Verso, 1994), 183.

John Berger, Why Look at Animals (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 5.

“Lin May Saeed on Art and Activism,” The New Institute, https://thenew.institute/en/media/the-freedom-of-bees.