On the eve of Gallery Weekend 2017, at 11 a.m., sirens blared and a city of 22 million dutifully marched outside, allowing emergency team leaders to check and count them. Mexico holds an earthquake drill yearly on September 19, both a preparedness measure and a memorial to the 1985 earthquake that killed 5000 residents of the city. Two hours later, a rumble sounded like a passing jalopy semitruck. As it grew louder, the ground began to tremor, visibly churning the asphalt in the street. Those who could, ran outside into the roil. Electricity lines and lampposts lazily swayed, incongruent with the collective seethe of adrenaline. For a society accustomed to immediate information, the reality of the force of the earthquake was eerily delayed. The improbably perverse coincidence of a second devastating earthquake on the anniversary of the 1985 one remains diabolically astounding.

The next day it was announced that Gallery Weekend was postponed indefinitely. It would have been grotesque to consider forging ahead. Many of the galleries are located in some of the most seismically unstable land in the city. Situated on the bed of a massive drained lake, when the earth shakes the soggy ground turns to wobbling aspic amplifying waves of movement. For days, news would come of another sagging or buckling building that had just given way. Collapse, as it happens, has an expanded time frame and a multitude of expressions.

Nearly a month later, it was announced that Gallery Weekend 2017 was rescheduled with an eye to revitalizing the neighborhoods in the city center affected by the earthquake. Since September 19, a gloom had settled over the city. Restaurants and bars with empty tables worked bored skeletal crews to mitigate losses. Galleries quietly shifted to focus on foreign fairs and collectors.

Gallery Weekend 2017 was marked by a sense of solidarity. Mexico City’s cultural landscape features a number of bitter divisions spawned from the branching off of the cultural family tree as former partners split and set up their own shops, strengthening the scene with their numbers, but creating bitterly genteel rivalries in the process. Gallery Weekend Mexico City is ambitious in its attempt to incorporate all these frenemies in one framework, but it’s still a business. If you want to play you have to pay.

Not everyone loves Gallery Weekend. Most agree that it does the city a service by breaking down the intimidating barriers of the gallery world to the public. But it’s fair to question whether the event is truly designed to succeed in that goal. For participating galleries, it is an exhausting, generally fruitless added expense wedged into an already costly and consuming fair schedule. Most participate out of a sense of duty, aware that the event mainly benefits Codigo, the magazine that organizes it, and its owner.

This year’s iteration kicked off with VIP events on Wednesday, September 19, the anniversary of both earthquakes. In commemoration there were two city-wide drills. Twice we filed out into the streets to be counted while buildings were mock inspected. Twice we locked wet eyes with neighbors triggered by shared trauma. Some raised fists in memory, mirroring the gesture calling for silence when listening for signs of life in the rubble.

Opening to the public the next day, Gallery Weekend felt emotionally hungover, mostly because it was so normal. The galleries assembled and played true to type: a curious arrangement of works by Pádraig Timoney curated just-so at Lulu; a hyper slick salon of large-format Thomas Ruff photographs towering at OMR; a large-scale multidisciplinary conceptual project by Iñaki Bonillas at kurimanzutto. There were some surprises. “Supports / Surfaces,” a small group exhibition of process painting from the short-lived French group of the same name at the young gallery Mascota packed an unexpected punch: so contemporary in its aesthetics and criticality, it’s a wallop to remember the works are nearly 60 years old. Similarly, the metal sculptures by James Metcalf at House of Gaga were grounded in a twisted bizarro-formalism and exploration of volume, material, and pain that felt relevant, almost reminiscent of the metal supports that a year ago screamed out of ruins of the collapsed building at the end of the block.

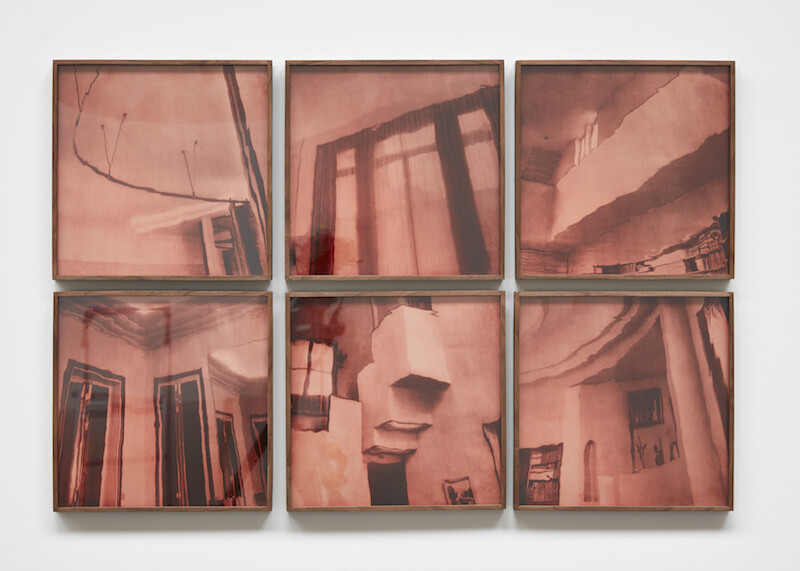

The weekend featured a handful of novelties. An old house in the Juarez neighborhood housed pop-ups by Paramo gallery from Guadalajara with a solo exhibition of monochrome paintings by Liat Yossifor as well as newcomer Mexico City gallery Aguirre with a series of snapshots of Lake Zurich by Kaspar Müller installed clipped to clothes lines. Next door, Nordenhake, a gallery with locations in Stockholm and Berlin, inaugurated its Mexico City space with a group show in a Porfirian mansion still damaged by the quake. Though according to the exhibition text the show is “defined from the notion of contingency in natural laws,” it felt cheap to use the dramatic cracks ripping through the building as window-dressing for an arrangement of objects. The text ambitiously explains that the works “outline different ways of questioning” no less than “the notion of absolute infinity” but with pieces featuring carved infinity symbols and a cast sculpture of the mathematical symbol for pi, ambition thinned in spots to illustration.

Perhaps inadvertent but nevertheless cathartic, Cenote (Mandala) (2018) at Labor tapped into the register of the latent mood. An architectural intervention by Pablo Vargas Lugo, who will represent Mexico in the 58th Venice Biennale, featured a deep hole bored through the concrete floor and into the red earth below. A spot of sunlight beamed through the darkened gallery from an opening cut into the roof. It had rained that morning so the gallery was damp, filled with the soothing smell of cold wet cement. Trees’ leafy tendrils reflected in the pool of accumulated water at the bottom of the muddy void. The Maya believed certain cenotes were sacred portals to the world of the dead, and they sacrificed jade, gold, and humans to their depths. Today the water-filled caves still hold potent spiritual significance, though now they are also hawked to tourists. Riffing on a sewer grate, Cenote (Mandala) ribs the lines between sacred and profane, nature and urban, endemic and epidemic. A piece like Cenote (Mandala) is essentially theater, but the familiarity of the manhole cover left open to reveal the dissociative puncture in the gallery floor required no suspension of disbelief. In the quiet sounded a reminder of the overwhelming awareness of earth as force— indifferent, inescapable, monstrous, alive.