The first lines of the song “I See a Darkness” (1999) by Will Oldham, aka Bonnie “Prince” Billy, go like this: “Well you’re my friend / That’s what you told me.”1 Dan Nadel, curator of “SAMARITANS” at Eva Presenhuber, suggests viewers read the lyrics while visiting the exhibition: they are printed in full in the press release. Instead, I listened to it about 25 times: “Many times we’ve shared our thoughts / But did you ever / Ever notice / The kind of thoughts I got?” An alt-country ballad, “I See a Darkness” is tender, bordering on saccharine. Its voice, piano, and guitars are aching, then hopeful, then not. It is about, among other things, friendship: “Well, you know I have a love / A love for everyone I know.” And though the artists in the exhibition, according to the press release, are “connected to at least one other [artist], and usually more, by friendship, inspiration, and influence,” the connections between the works feel tenuous.

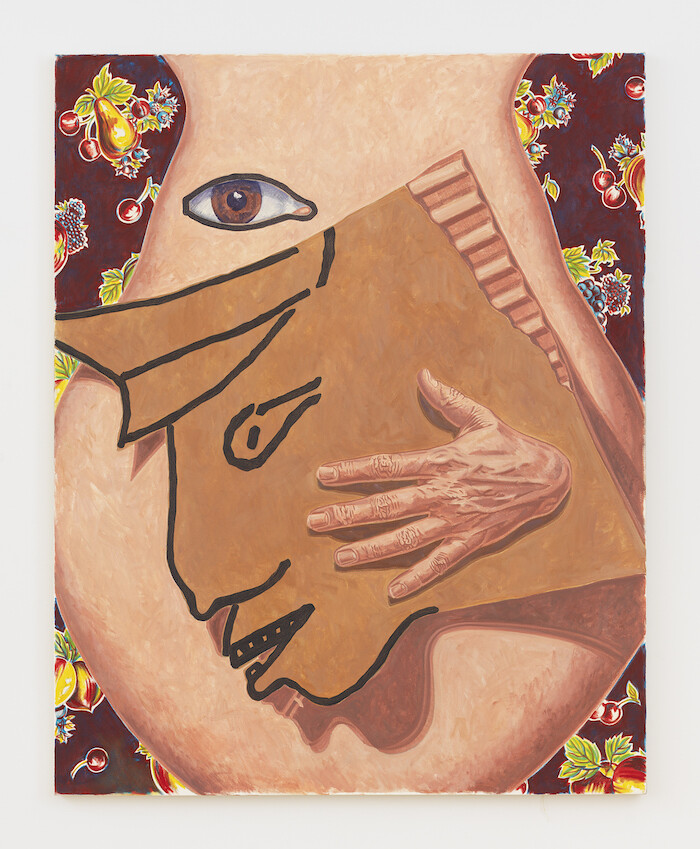

On a wall in the first room is Xeno (2017) by Takeshi Murata, a slick, totemic, geometric sculpture whose enamel paint glows like radioactive candy. On the wall adjacent is The Golden Age: The Jaguar and The Tapir (1985), a huge painting by Joan Brown with the titular animals in the foreground, eyes fixed on the viewers. In the next room, there’s Jason Fox’s Jekyll (2018), a pair of verdure and blood-red figures transposed atop one another. One seems to be smoking a gigantic joint. I’m surrounded by figures and figuration: Sarah Peters’s conjoined two-headed sculpture Glossolalists (2019), Laurie Simmons’s creepy photo of a doll uneasily bestriding a wall (The Love Doll / Day 25 (The Jump), 2010), Alan Turner’s painting of a disembodied hand and what seems to be a fleshy vase, eye protruding (Mask, 1993). The effect of all these bodies and body parts is such that, even with Joe Bradley’s simple wooden box in the middle of the room, I sense that there’s maybe someone or something waiting inside.

In the room downstairs, there’s a set of lovely, furtive illustrations by Christopher Forgues, inky comic book-like characters peeking around walls or trapped as avatars, drawn on the grid of a calendar. I can smell the cork off Huma Bhabha’s sculptural humanoid Past Life (2018). The leggy bottom half looks like rotten wood or burned charcoal, the feet and toes curled in gargoylish repose; the Styrofoam head has no face but still it stares at me. In Ellen Berkenblit’s Captain of the Road (2018), a leopard growls at the industry surrounding it. Nurses of Gamma (2018) by Gary Panter is set in a cold hospital-cum-spaceship, three nurses rushing to save a patient as a big green one-eyed alien looms behind them.

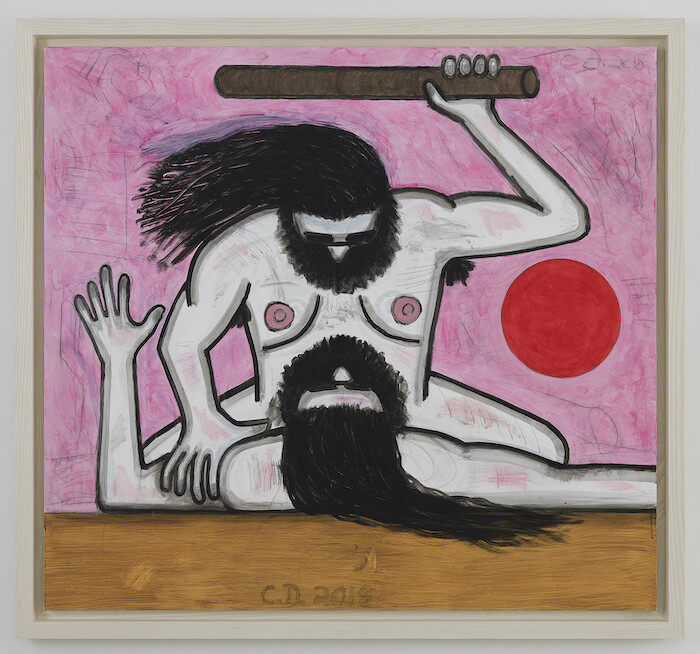

All the figures—human, animal, alien, mutant—reflect Nadel’s interest in psychedelic pop and anti-modernism. While the presentation of works can feel cold and institutional, the variety of worlds and styles represented by the selection has a centrifugal effect, spinning me out in too many directions. Mike Kelley’s Free Gesture Frozen, Yet Refusing to Submit to Personification (Violet Fingerpainting) (1998)—violet smudges on wavy wood, which resembles an abstraction of the teddy bears Kelley employed elsewhere in his work—contrasts with Carroll Dunham’s untitled 2018 painting of a nipply man pinning down another, about to strike him with a baton. Though quite different, Kelley, Dunham, Panter, and Brown serve as arch-influencers for the exhibition: in an email, Nadel told me that all the artists in the show would probably cite at least one of them as influences. This, along with the fact that all of them engage in figuration, sums up the conversations these pieces are having.

All the artists work from a similar position of resisting a signature medium, style, subject, or genre. But the show lacks a theoretical thrust. Nadel’s 2015 exhibition “What Nerve! Alternative Figures in American Art, 1960 to the Present” at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum (and later New York’s Matthew Marks Gallery) offered a much-needed counter-history by examining alternative art movements outside New York. It’s unclear what “SAMARITANS” achieves besides displaying Nadel’s personal tastes. It brings together some of the artists involved in or influenced by the collectives featured in “What Nerve!” (such as Destroy All Monsters from Ann Arbor and Forcefield from Providence), but it’s a loose constellation, housed in what seems like the wrong universe.

I come back to “I See a Darkness,” which is meant as a guide. The song yo-yos from quiet optimism to swelling melancholy, sentimentality to gloom. Why is this intensely personal song about the highs and lows of friendship, love and loss, meant to usher me? The incongruity between the song and the show is confusing. This may be because of my particular emotional state at the time: “And you know I have a drive to live I won’t let go / But could you see it’s opposition, comes rising up sometimes?” But having a song as a guide sets an expectation that the exhibition’s separate elements will come together cohesively and tell a story, something more than its hazy concerns with figuration, hallucination, and weirdo mythologies. I want to feel the fire of camaraderie, not the dim heat put off by the candle of influence: “Well, I hope that someday, buddy / We have peace in our lives / Together or apart.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LAriDxTeed8.